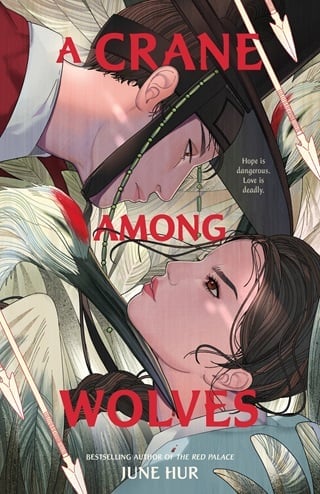

A Crane Among Wolves

1. Iseul

July 1506

Never travel beyond Mount Samak.

Halmeoni’s words echoed in my ears, the memory of her warning tugging at me to turn back. But I could not; I had come too far. Pine needles scratched my face as I pressed through the forest, disregarding my blistered feet and blood-drenched sandals. My legs felt numb, not used to trekking for days over rocky slopes, steep ravines, and rushing rivers.

Iseul-ah, Grandmother’s voice tugged again. You must stay away.

Wrenching my cloak from a tangle of branches, I hobbled down the narrow path and paused before a tower erected like a gravestone at the edge of the forest glade. Etched into the granite were the words:

TRESPASSERS WILL BE EXECUTED.

The damned king. The territory beyond had once been home to tens of thousands of people, until King Yeonsan had evicted them, turning this half of Gyeonggi Province—from the town of Yongin all the way to Gimpo, Pocheon, and Yangpyeong—into his personal hunting grounds.

“Heavens curse him,” I snarled, stomping out into the open.

The sky was heavy with rain clouds, the air thick with humidity. Up ahead was a road that cut through grassland. And past the veil of mist, lush green mountains loomed, quiet observers who must have witnessed dozens of men, women, and children wander into this wilderness—and never escape it. I might die out here, too, if I let my focus slip even for a moment.

I ran a finger under my tight, sweat-drenched collar.

If I lost my way out here, there would be no one to give me directions. I couldn’t make a single wrong turn.

Rummaging through my travel sack, I snatched up my ink-drawn map, studying it for the hundredth time. The route I was to take wound through abandoned rice paddies and demolished villages, over small mountains, and through valleys, then along the Han River, and at last to the fortress gates of the capital. The journey was a long one, and I was growing impatient. Suyeon needed me. She was waiting for me there, and I was her only way home.

“You had better wait for me, Older Sister,” I rasped, continuing down the dusty road. “I am almost there.”

Older Sister and I had faced horrors before—when royal soldiers killed our parents, and we’d escaped to Grandmother’s home before we could be exiled to an island far away. Grief had strained our already waning bond, rendering us mere strangers living beneath Grandmother’s roof, our interactions reduced to husks, of mumbled remarks and cutting glares. How shocked Grandmother must have been when she discovered my note, declaring that I’d left to find my missing sister.

I was shocked myself.

When my heart was far from Suyeon, I had seen her as a sister who was burdened by me and who carried herself with the irritating air of an afflicted martyr. But my heart had clung close to the memories of her during the past three frightening days. I no longer saw a sibling I resented but the girl our parents had adored, the cherished child whom Mother had conceived after eight long years of waiting. And once born, Mother and Father had showered her with an abundance of love, treasuring her as if she were worth more than a dozen sons. I had cherished her, too, when we were younger. She possessed a natural silliness and would entertain me until I broke out into squeals of laughter. She would also assemble scraps of material, fashioning them into whimsical puppets, performing enchanting tales of folklore to me, her delighted audience. I had laughed a great deal as a child because of her.

This sister of mine was gone.

Do not die, Older Sister. Stay alive. You must.

I forbade myself from resting, except to pause briefly by a trickling stream. I hadn’t eaten since the morning—I’d packed enough for only two days, not three. Scooping up handfuls of water, I drank until my stomach felt heavy, the hunger less excruciating. Then I washed the sweat and grime and tears from my face. Leaning my weight against a rock, I lifted myself back onto my feet, and I was once more on the road.

I passed by a rag doll, an abandoned sandal, a leafy plant erupting from a crack in the road.

The eerie quiet chilled my skin as I stood before a town, as hollowed as a bone. Weeds crawled over shadowy huts, devouring walls and roofs. The streets that had once bustled with crowds, filled with voices and merriment, were now deserted. Families, neighbors, friends—they were all gone. They had either escaped the province in time or remained to guard their homes, only to be slaughtered by the king and his army.

I wondered if their ghosts were watching me now.

Why are you here?I imagined them asking. This is forbidden territory.

The truth was too unbearable to face. I tried to beat it aside, but as I trudged on, my mind sank into the memory of three days ago. I was once again the heartless and self-centered Iseul, the younger sister who could not stand to be under the same roof as her older sister.

I had run out of the hut after a dreadful argument with her, and it had been my fault. It was always my fault. I cannot bear her, I had snarled, even as guilt had plagued my conscience. I wish she had died instead of Mother, instead of Father!

I hadn’t meant it, truly, but as though my thoughts had summoned him, King Yeonsan had prowled into our village. The treacherous king who kidnapped women as his pastime—the one who stole the married and the betrothed, the noble daughters and the untouchables alike. He did not discriminate. And my sister, who must have followed me out, was as lovely as an azalea in full bloom.

I had no doubt in my mind that His Majesty had taken her.

“Halmeoni,” I whispered, the ghost town now behind me. Raindrops spotted the dusty road, and the mist shrouded the distant mountains in white. “I will find Suyeon. And I won’t return home until I do.”

I trudged through the rain, my head angled against the torrent, and walked until the night thinned into an early-morning gray. Beyond exhausted, I wanted to drop to the ground and curl up. By midafternoon, I finally saw a hamlet in the near distance. No weeds were crawling over the huts. Instead, the roofs were thick with golden straw thatching, the clay walls smooth and unblemished. A bell tolled somewhere in the town, followed by the sound of scurrying footsteps and creaking wagon wheels.

The sounds of life.

I pulled out my jangot, an overcoat I’d once worn over my head as a veil. I wore it now, not out of fashionable etiquette, but to conceal my face. I did not wish to be seen—or remembered. I was a fugitive, and a village did not always mean safety. I clutched tight to the sides of my cloak, clamped the travel sack under my arm, and focused on my steps. Put one foot ahead of the next, I told myself, determined not to collapse. As I entered the hamlet, out of the corner of my eye, I noticed handbills pasted onto public walls. The same handbill had been plastered around Grandmother’s village. I’d read it over so many times I could recite it by memory.

THE KING DULY INSTRUCTS THE PEOPLE A KILLER IS ON THE LOOSE.

PERSUADE ONE ANOTHER TO SEARCH FOR THE CULPRIT—

I tensed, looking up as a woman and her ox-drawn wagon appeared down the dirt path, the wooden wheels turning precariously on their axles. She stopped to hold my stare, and I knew what she saw: a grim-faced girl with her chin perpetually raised, bearing the haughtiness of a yangban aristocrat, yet garbed in a dirty silk dress.

“Excuse me,” I rasped, my voice scratched from disuse, “but would you point me to the inn? If there is one here.”

Without a word, the woman pointed vaguely down another path then continued on her way, leading her ox and cart along.

I followed her direction and soon found myself before a long, thatched-roof establishment with a spacious yard spotted with travelers. Clutching my veil tighter, I studied the strange faces. No one can be trusted, the past two years whispered into my mind. No place is safe. I pulled the jangot higher over my head, to ensure that if anyone were to look, they would see only a pair of eyes, dark with a warning: Stay away from me.

I took in a sharp breath, squared my shoulders, then stalked into the bustling yard where some merchants were unloading their goods. Two children washed their faces on the veranda that wrapped around the inn. Weary travelers ate and quietly conversed. Steam billowed from the kitchen, and I took in the mouthwatering scent of soybean broth.

My stomach twisted; my head swayed. Suddenly, the exhaustion of the three-day journey struck me hard. My knees buckled, and I stumbled backward, the earth tilting beneath me until a strong hand gripped my arm.

“Careful.” It was a female voice.

My hazy vision cleared and focused on a young woman who looked to be no older than I. Adorning her head like a crown was a fashionable gache wig, glossy black hair braided into thick plaits and arranged in coils atop her head. Her eyes were just as black, and sparkling, too. A scar ran down from her right eyebrow.

“A traveler has arrived…” She tilted her head to the side, as though the heavy wig were as light as a feather. “And it appears my guest has come from afar.”

“Yes,” I croaked, then cleared my throat. “I am from—” Chuncheon. Instead, I gave her the name of another nearby town.

“Hmm.” She examined my dress, my bloody sandals, then her gaze locked onto mine. “You went through the forbidden territory, did you not?”

“Here one comes for a warm meal and shelter from the rain,” I said stiffly, “not for an interrogation.”

“Rest assured, I shan’t tell anyone,” she whispered, then gazed off into the distance—perhaps beyond the road, the reed field, to the stone tower. “All who travel through that half of Gyeonggi Province look as though they’ve journeyed through the underworld,” she murmured. “I’ve seen the look in their eyes. In my own father’s eyes.” She let out a little breath, and a smile reappeared on her lips. “Are you in need of room and board?”

I needed to rest. Desperately. “I am…”

“Then you have come to the perfect place,” she said, and chivalrously offered me an arm. “My inn will take good care of you.”

“I can walk on my own, thank you,” I bit out. But when I tried, my knees wobbled and I unintentionally reached for her. I tried to pull away at once, but she stubbornly held my arm.

“You look like you’ll faint at any moment.”

Shoulders tense, I let her help me as I staggered farther into the innyard then sat down on a raised platform where three other travelers were hunched over low-legged tables, wolfing down stew. A fourth man, wearing a straw hat, nursed his bloody fist. I dragged my weight around and settled before an empty table, holding the edge to keep myself steady against the growing dizziness.

“Wait here!” the innkeeper chirped. “I shall bring you a most hearty meal.”

I blinked hard, wishing the light-headedness would go away, hoping I wouldn’t pass out in the company of strangers—including the innkeeper. Her kindness was too sweet, too suspicious. I slipped out my map, flipped it to the back, and stared at the face of my sister, which I’d drawn in ink. “Stay alive, Older Sister,” I whispered to the drawing, “and I will, too.” Her delicate eyes stared back at me, her calm and graceful expression—

The back of my neck prickled. Someone was peering over my shoulder.

I quickly folded the sketch and glanced up to see the smiling innkeeper. She proceeded to unload a steaming bowl of boiled herbs. Not a single chunk of meat to be found. It wasn’t the sort of hearty meal I had grown up with, but I’d learned these past two years that more than half the kingdom survived on what could be foraged in the mountains.

“So,” she said, “what brought you here to Hanyang?”

“Why do you wish to know?” I asked, my voice clipped.

“I like to know who my guests are. You are searching for someone?”

“No.”

“You drew that?” she asked, gesturing toward the paper in my hand.

“Yes.”

“The boy in the picture looks too young to be your father.”

“It is a woman,” I snapped.

She let out a most obnoxious laugh. “I jest! Is she your sister, then?”

“Even if she were”—I stuffed the sketch back into my travel sack—“it should be no concern of yours, ajumma.”

“‘Ajumma’?” The amusement in her eyes brightened. “I am neither a middle-aged woman nor am I married. In truth, I have no interest in ever marrying, even though I do have quite the line of suitors, if I do say so myself.” She paused, as though waiting for me to laugh. When I did not, she continued. “I am only nineteen. Come, you look at me with daggers in your eyes. I only wish to help. You’ve come searching for your sister, and you can’t be more than eighteen.”

I was seventeen.

“Do you not have anyone to accompany you in your search? A father? A mother?”

They were both dead. And I had no patience for nosiness. I cut her a glare, preparing to say something biting. But then it occurred to me that while her curiosity was relentless, it also posed an opportunity. Innkeepers could be storehouses of information, of gossip. And what I lacked was knowledge of the capital, of how to get to my sister.

“You crossed King Yeonsan’s hunting grounds, risked your life by doing so,” she spoke in a whisper, seemingly unaffected by my reserve, “and you are here near the capital. Did she run away—?”

“No, madam,” I said coolly, watching her closely. “She was taken from our village three days ago.”

The innkeeper sighed. “You too.”

Here was my chance. “You know of others?”

She cast a glance around. No one was in hearing distance except a man across from me, but she seemed to pay him no heed. “Many. The hamlet has even installed a bell, which is rung when the king is to pass through, to warn the young women who dwell here. That is, what remains of them. I have not seen a girl my age in months.”

“The king passes through this village himself?”

She nodded.

We both fell quiet, and I noticed then that the straw-hatted man across from me was eavesdropping. He had stilled, no longer dabbing a cloth against his bloody knuckles. He also wore a straw cloak—though the rain had long stopped—and the brim of his hat was lowered over his face, offering me only a glimpse of his bearded and middle-aged complexion.

“How…” I dug my nails into my palm. This was dangerous, the question I was about to ask. A question that could lead to my imprisonment and execution. Trust no one, I had told myself, yet in this moment, I had no alternative—there was no one else to rely on. “Would there be some way that I might see my sister?” I dropped my voice as low as possible, glancing at our eavesdropper. “Just to speak with her, to hold her hand. Nothing more.”

The innkeeper chewed on her lower lip as she gazed past me at the man, then a look gleamed under her slender brows. “Did you know, when the king goes hunting, he takes his courtesans—”

I bristled. “You mean the girls he’s stolen.”

“—he takes hundreds of his most favored courtesans to accompany him,” she continued, ignoring my interjection. “I’m sure His Majesty wouldn’t notice if one girl went missing. For a moment.” Quickly she added, aware that this kingdom abounded with spies, “Just to hold your sister’s hand, as you said. That cannot be treasonous, I should think. The king forbids husbands from ever meeting their wives, but His Majesty has made no mention of sisters…”

It took a moment for her words to register, and the barest flicker of hope drifted through me. “When…” I swallowed, trying to steady my voice. “When does His Majesty go hunting?”

“In the summer, often.” The innkeeper propped the tray against her waist. “You must have heard the village bell ring when you arrived here.”

Following her gaze, I glanced behind me. A dark thread of movement crawled over the distant hill, red flags billowing under the blazing sun. I swiped an oily strand of my hair away, then quickly buried my hands in my skirt to hide their trembling.

“The king keeps his women close,” came a male voice, so gruff and commanding that I flinched. It was the eavesdropper, the brim of his straw hat still lowered, his face an ominous shadow. “And some of the finest swordsmen and archers guard His Majesty… and his women.”

The innkeeper and I both stared at him.

Nonchalantly, he continued to nurse his bloody fist as he said, “To attempt to steal your sister right under His Majesty’s nose will result in both your deaths. You won’t even get close enough to touch her before you’re shot dead with an arrow.”

“I did not say I would steal her,” I said calmly, even as cold gathered in my chest. This man could be a royal spy. “I simply wish to see her.”

“Your love for your sister is admirable, but I have seen this love drive countless men to their demise. I would beware, if I were you.”

“That is Wonsik ajusshi,” the innkeeper whispered. “He is like the guardian of this inn, always fighting off cutthroats and thieves, so I would heed his advice.” She then waved her hand with a flourish, as though to sweep aside my anguished look. “Do not look so downcast,” she said too merrily. “So long as your sister lives, there will always be a way back to her.” With that, she turned and walked off, taking with her the trace of hope I’d felt.

My gaze dragged back to the dark cloud of the king’s approaching procession, and my stomach clenched around the awful thought that my entire journey may have been futile. That I was helpless and that my sister was gone, forever.

“Nangja,” Wonsik interrupted my gloomy thoughts, addressing me as a young maiden. He slipped the bloody cloth away, and while he examined the cuts on his knuckles, he said, “Eat your meal.” He flexed his fingers, testing. “You cannot journey back home on an empty stomach.”

“I will not be returning home.” I nevertheless picked up my wooden utensil and shoved spoonful after spoonful of soup into my mouth. “Not without seeing my sister.”

The eavesdropper continued to examine me, then he left his table and retired to his room.

I picked up the bowl and gulped down the remaining broth. I wiped my mouth with the corner of my sleeve, then stared into the empty bowl. I had nothing, absolutely nothing, to help my sister with; I did not have the strength and power of a military general, nor the cunning of a great strategist. I was simply Iseul. A troublemaker. A blemish on my sister’s life.

“Madam Yul!” a panicked voice erupted. “Madam Yul!”

Everyone at the inn perked to attention, lifting their heads. I, too, glanced around, then I caught sight of a lanky youth dressed oddly—in a bright red robe and golden sash band. He came charging into the yard, then bolted straight toward the innkeeper.

“A murder! Right outside the village,” he gasped, his face ashen. “And I overheard the village elder say that he’d reported it to the capital police bureau. The village elder thinks Nameless Flower has struck again. That means this is the twelfth victim!”

Nameless Flower.

That was the sobriquet the populace had given to the anonymous killer at large somewhere in the kingdom, the one who had murdered government officials, each of them one of King Yeonsan’s sympathizers. Others referred to the killer as “The Guardian,” for he would steal rice from the wealthy and leave it at the home of starving peasants. Nameless Flower. His name now ricocheted inside my skull as the two conversed in hurried whispers.

“Could it be a coincidence?” the innkeeper asked. “That Nameless Flower struck this very day—when the king is to pass through with his hunting party?”

“I don’t think it a coincidence at all.”

Madam Yul ran a nervous hand along her throat.

“The village elder doesn’t want the king to see the crime scene, so he’s moved the corpse into the reed field,” the young man said, growing paler by the moment. “The elder fears that His Majesty will light this hamlet on fire in outrage if his hunting day is marred.”

I had no interest in the killer anymore.

I half rose, meaning to retreat to my room, but the innkeeper hadn’t pointed out where I could stay. As I turned to interrupt their conversation, I noticed another handbill fluttering on the public wall.

THE KING DULY INSTRUCTS THE PEOPLE A KILLER IS ON THE LOOSE.

On the day soldiers had first posted this handbill on public walls, I’d wandered out of Grandmother’s home to read it. I should have hidden in the hut—it was dangerous for a convict’s daughter to roam a village full of soldiers, but I’d ventured out nevertheless.

PERSUADE ONE ANOTHER TO COME FORWARD WITH INFORMATION REGARDING THE KILLING OF GOVERNMENT OFFICIAL IM, AMONG THE TEN OTHERS. HE WAS FOUND DEAD, A BLOODY MESSAGE THAT SLANDERED HIS MOST GRACIOUS MAJESTY SMEARED ACROSS HIS ROBE. ANYONE WHO RENDERS MERITORIOUS SERVICE WILL BE OFFERED A GRAND REWARD.

“Grand reward,” I whispered bitterly.

Those two words had cast a spell over me the day I’d first read them. I had stayed out too long, fantasizing about what the king could give my family if I’d found useful information. I had imagined a life once more surrounded by the safe and secure mansion walls, perfumed by an immaculate garden, and endowed with servants who would come running to tend my every need. My life would finally return to normal, to the perpetual state of comfort and ennui where my utmost concern would be the condition of my nails, the paleness of my skin, and whom I’d be arranged to marry. On my return to our thatched-roof mud house, I had felt a glimmer of hope I’d not felt in a long while, only for it to be dashed away by my sister.

Do not be stupid. No one will save us, she’d rebuked me, especially not the king.

Our clashing had spiraled into vicious words that had sent me hurtling out of the hut two days later.

I pressed my fingers into my eyelids, wishing I could turn time around. I wished that I’d never left the hut, that I had never laid my eyes on those two words. Grand reward…

An odd floating sensation hovered along the outer reaches of my consciousness. Distant thoughts, gathering like clouds, and then they were gone. I frowned, searching for whatever it was I’d lost. But before I could grasp it, the innkeeper rushed across the yard.

“Uncle Wonsik!” She rapped on the latticed door; it was the room where the straw-hatted eavesdropper had retired to. “Samchon!”

When the door slid open, she spoke low-voiced into the shadows, “I think the killer you’re looking for has struck again.”

After a quiet moment, the man lumbered out of his room in his straw hat, drawing himself up to his full height. He was tall, broad-shouldered, and athletically built. A humid wind billowed by, lifting his straw cloak just enough to reveal a sword strapped onto his back. The scabbard was glossy black, heavily decorated with gold—he was no commoner.

“The messenger told me the corpse was relocated deep within the reed field,” Madam Yul explained. “There is a bloody pathway marked by all the dragging, so we will not miss it.”

“I need to speak with the village elder first. Where is he?”

“North of the field, from what Yeongho told me.”

In that moment, I understood what I needed to do. Fear wavered through me, but I beat the hesitation aside and dug my nails into my palm. King Yeonsan was offering a grand reward. If I could catch the killer, then perhaps—just perhaps—His Majesty would return to me the sister I had wronged.

I’d do anything the king decreed, absolutely anything at all, to see Older Sister one last time.