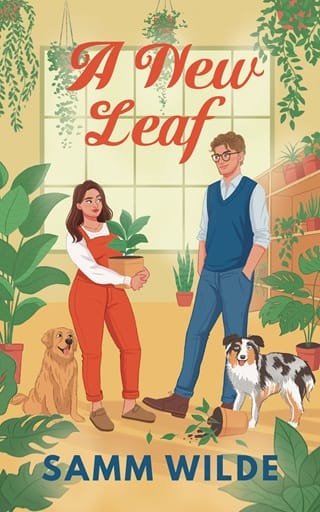

A New Leaf (Hemlock #1)

Chapter 1

Chapter One

Charlie

Will there ever come a time when I stop being tired?

Honestly, there must come a point when I won’t want to just flip the sign to “Closed,” crawl under this table, and sleep until I wake up in a different year.

Or a different decade.

I let out a giant yawn, shaking my head awake as I continue pruning this monstrosity of a pothos. Dark green vines trail to the floor as I begin clipping away stems slower than a grandma walking into Bingo.

Perseverance is the word of the day while I try to push through the fatigue and down my second Diet Coke before noon.

I run on three major sources of fuel: Diet Coke, social anxiety, and the optimism of retirement in thirty-something years. As the relatively new owner of A New Leaf, a quaint plant store in Hemlock, Oregon, I get to be around plants all day. Which is great. Mainly because plants don’t talk, and I’m not the biggest fan of conversation.

A match made in botany.

Although plants and I have had a rocky relationship in the past, they’re starting to grow on me . . . sort of.

The store has immaculate vibes, all thanks to my parents.

When customers walk in, they’re instantly greeted by a jungle of lush, green, indoor houseplants. The space is airy, with white walls, wooden floors, and skylights. Colorful plant displays are set up all around the shop, showcasing various plants such as cacti, philodendrons, calatheas, and more. Plants in hanging pots cascade down from the ceiling, making it feel like you’re being completely enveloped in a big, green hug.

It’s a plant lover’s paradise.

When my parents passed away, just under a year ago, I made the choice to move back home from Portland. This store was their baby and it only felt right to take it over in an effort to keep their memory alive. My younger sister travels too much to manage the store, and my older brother already has his own business. That left me, and my anti-social self, to take over A New Leaf.

Uprooted is the best way to describe the last year of my life. Since starting over from scratch, every day is now filled with unpredictability.

I wish life had a self-help manual. That way, whenever I hit an obstacle, I could thumb through the pages that provide guidance on how to handle said situation.

Shaking my head to myself, I regret not paying attention to that one business course I took during my undergrad. Instead, my e-reader is currently filled with books on how to run a business, soup recipes for one, and shirtless men wearing kilts.

I like what I like and I won’t apologize for it.

Still clipping away at the plant before me, I fixate on how deeply I miss my mom and dad. I went from speaking to them almost daily to . . . nothing.

It feels weirdly silent.

And that’s because it is.

I still don’t have it in me to delete their text messages on my phone. A delusional part of me hopes they’ll send me a message, even though I know that’s impossible.

Since they died, there’s been a constant ache in my chest that stays with me every day. This store feels like the last living, breathing piece I have left of them, and I’m determined not to let it fail. Just the thought of closing the store for good makes me physically sick to my stomach. This plant shop was them, right down to the creaky floorboards, chipped green paint, and dirt-covered countertops. People in Hemlock have such a deep love for this store. When my parents were still alive, residents and tourists alike would regularly hang around the shop every Saturday afternoon. The whole town was in mourning when word got out about their unexpected deaths.

Tears burn behind my eyes as a lump begins to grow in my throat. I quickly blink away the unshed tears and tell myself that I can cry later since I have a store to run.

There’s one, eerily quiet customer in the store, and the last thing I need in this small town is everyone knowing I was crying.

Everyone knows it’s the quiet ones you have to keep your eyes on.

Myself included.

Still laser-focused on the pothos in front of me, I hear the bell chime from above the door, and a rush of autumn leaves drifts inside with the breeze.

A booming, frantic voice fills the small space of my parent’s store.

Well, I guess it’s my store now.

“Oh my god, Charlie!” the individual screeches. It doesn’t take a detective to know that the screech is coming from Mrs. Jenkins, the town busybody who can’t go more than an hour without gossiping to someone about something .

Closing my eyes, I mumble, “Fuck me, not again,” as I hear the scuffle of her too-expensive shoes reach the counter that I’m standing behind.

Her eyebrows raise. “I’m sorry, what did you say?”

I drop the pruning shears on the wooden counter and wipe my hands on my apron, “Oh, I said duck confit is for dinner again. Anywho, how can I help you?” I place my hands on the counter and give her my best, phony, customer service smile.

Her eyes narrow. “That’s an interesting meal choice.”

“Well, what can I say? I’m an interesting woman,” I reply, my tone dripping with sarcasm.

“Right. Well, Charlie, I was hoping you could help me with something.” As she speaks, I glance down at my comically lazy golden retriever. Vera, the dog I also inherited from my parents, perks her head up, gives a dramatic groan, and promptly falls back asleep—doing what I only wish I could do right now. Inspired by Vera, I make the mistake of letting out another slow yawn.

“—and I was hoping you could show him around,” Mrs. Jenkins finishes, staring blankly at me. “You weren’t paying attention to anything I was saying, were you?”

My tired eyes glance back over to her. I give a sheepish smile and slowly shake my head. “No. I wasn’t.”

Mrs. Jenkins gives me her famous disappointed sigh.

And I couldn’t care less if I tried.

Since my parents died, the people in town have gone easier on me and my Oscar the Grouch attitude. Granted, I’ve always been a little curmudgeonly, but my crankiness really escalated after they died because of all the added responsibilities. Even though I’m a grown, thirty-four-year-old adult woman, I’ll always need my parents. And having them missing from my and my siblings’ lives is a wound that I don’t believe will ever heal.

Mrs. Jenkins clears her throat. “As I was saying, my nephew is new to town and is opening a coffee shop down the road.” Her tone is a touch too happy and exuberant this early in the day. “I was hoping you could show him around town since I’m leaving on vacation,” she finishes. Mrs. Jenkins looks at me with such optimism, and all I can do is stare back at her with my brows furrowed.

She’s stumbling over her words now. “It’s just . . . you seem like you could use a friend.”

I don’t need one.

She’s still rambling. “You’ve been holed up in this shop with your dog forever!”

That’s how I like it.

Vera’s head perks up again, giving Mrs. Jenkins the side eye while making a loud, disapproving groan that turns a nearby customer’s head. Sometimes, I truly believe this dog is a sassy old lady reincarnated.

Closing my eyes in frustration, I pinch my eyebrows together and give a weighty sigh. “Isn’t there anyone else available to help? I have a lot on my plate right now, as you can see.” Mrs. Jenkins looks around my store with only one customer, then glances over at the drooping pothos in front of me, and finally down at Vera. The dog groans again and immediately flops down, having zero capacity for this nonsense. Mrs. Jenkins slowly locks eyes with me, giving me a quizzical look.

I’m a people pleaser to my core, and even though I dislike 92 percent of the population, saying “no” to anyone is still difficult for me. I’d rather not spend the next few weeks helping some random man. He’s got a phone, which has a map, which presumably can show him around. I’m sure he’s a big boy and can figure it out.

With a slow shake of her head, she says, “No, hun, I’ve asked, and everyone else has said no.” Mrs. Jenkins and I have a brief stare-down until I notice her lips start to twitch in an unsettling way that makes everyone in town feel uneasy.

She knows my people-pleasing weakness. If I had a dollar for every time I said yes to a favor, I’d finally be retired on a beach somewhere, drinking margaritas while watching shirtless men play volleyball.

Looking up at the ceiling, I let out a groan so loud that the lone customer jolts with surprise and hastily leaves. My head drops to see Mrs. Jenkins looking at me with such hopefulness, while I’m giving her a blank stare.

The exasperation is heavy when I’m the first to give in. “Fine.” I throw my hands up. “But I won’t be charming or nice. I’m getting in there, doing the mission, and getting out quickly.” My finger is now pointed directly at her.

Better to be honest than to set false expectations.

“I wouldn’t expect anything else, dear,” she says before promptly turning to leave.

“Good-almost-afternoon, my grumpy little Gremlin!” sings my coworker Marnie, my only employee at the store. Extroverted to the heavens, covered in tattoos with long, jet-black hair, and fierce as they come—she’s a force to be reckoned with. She usually comes in to work a bit later since she teaches art classes at the community center some evenings and needs the mornings to prep.

“I thought I fired you this week?” I say without looking up from my laptop at the counter. I’m researching common houseplant pests and am quickly regretting it. Photos of these tiny bugs are making me itch.

“You did. Three times, actually! And it’s only Tuesday. Quite impressive if you ask me.” She shrugs, inspecting a few plants.

I let out a small laugh, shaking my head. You know how there’s always an extrovert who adopts an introvert by accident? That’s Marnie and I. She saw me, sunk her talons in, and we’ve been stuck together ever since. I close my laptop, shove it under the counter, and rub my tired eyes.

“I saw Mrs. Jenkins prowling around out there. She didn’t stop by, did she?” Marnie asks, eyeing me suspiciously as she puts her apron on.

Letting out a sigh that radiates deep in my chest, I round the corner of the counter with a spray bottle in hand to begin misting some of the tropical plants. “Unfortunately, yes. She wants me to show her nephew around Hemlock,” I reply, mildly irritated.

“Is that a euphemism for something?” she says, wiggling her eyebrows.

I’m definitely ignoring that comment.

“Apparently, he bought the building a couple of doors down and is opening a coffee shop there. Did you even know that building was for sale?” I ask, misting a monster of a Monstera. They don’t name them “monsters” because they’re tiny. I’m waiting for the day that it takes over the entire store and swallows me whole. Which, at this point, sounds like a dream.

Marnie walks behind me, organizing the succulent table. She glances over at me from the corner of her eye. “Yes, I did, because unlike you, I pay attention to my surroundings. The world could end, and you’d be too hyper-focused on a new plant fertilizer or propagation technique to notice.”

I stop what I’m doing and look at her. “Okay, first of all, you’re fired.” She nods knowingly. “And second, it’s been almost nine months since I took over the shop, and I still have no clue what I’m doing.” A thought about my situation hits me. “Then again, maybe this guy has useful insights on running a small business, since he’s opening one here.” I sigh wearily. “I was a software engineer. Programming? Easy. Designing distributed systems? A breeze. Keeping overgrown weeds alive? I’m clueless.”

Marnie chuckles, adjusting her glasses on her nose. “Fair point. But, you could look up and around sometimes. I’m sure you can only read so much about . . . prop—whatever that word is.” She waves her hand.

Setting one hand on my hip, I point the spray bottle I’m holding at her. “Propagation. And, listen, one day, knowing the difference between soil and water propagation will come in handy.” I pause, getting an idea. “Oh! Maybe you could tell your next date about propagation? But you have to get the word right first.” I shrug nonchalantly, continuing to mist the plants.

Marnie hums. “Yes, because nothing says ‘take me to bed and rearrange my insides’ like walking a man through the finer points of plant propagation.” She dreamily sighs. “You know, I do have some seeds that could use fertilizing.”

The water bottle almost slips from my grasp as I look at her in disbelief.

Marnie waves her hand, dismissing me. “Hush. Don’t get your overalls in a twist. Also, you didn’t explain why Mrs. Jenkins wants you to hang out with her nephew?”

“Well, she’s going out of town when he’s opening his café. I guess she needs someone to be a ‘friendly face’ for him. Or emotional support. Neither of which I’m great at, as you already know.” I set the mister down and grab a cloth to wipe down some of the larger leaves of this plant.

Her head tips back with a laugh. “Oh, I know. Remember that time I came crying to you because that guy I was dating in our math class was flirting with the TA, and you told me to ‘grow a pair of ovaries and get the fuck over him.’ Ruthless.”

There’s nothing wrong with tough love.

Especially when it comes to steering your best friend away from mediocre men.

“Let me guess, you felt too awkward to say no to her face because she does that weird lip thing that makes you uncomfortable?” Marnie snickers. “You know, it never ceases to amaze me how someone so crotchety like you can be so nice and accommodating.”

“Oh fuck off. But yes . . . I could see the beginnings of that weird lip thing when I zoned out.” I shiver. That lip thing she does is so disconcerting.

“Ahh, my people-pleasing, petulant little Gremlin is getting a new friend! How sweet.” She claps. “Do we know how old he is? Is he hot? Is he single? What’s his zodiac sign? Can I ask him to fertilize my seeds?” she says too excitedly, wiggling her eyebrows once again.

I groan, refusing to make eye contact with her as I wipe down more leaves. “You know I’m bad at asking follow-up questions.”

“Yes, I do know. That’s how you ended up in city jail that one time and your dad had to bail you out. Your dad literally went to the grave with that secret because he refused to tell your mom for the sake of her blood pressure.” She chuckles.

My chest tightens at the mention of my parents. My dad and I had a special bond—an unspoken bond, I’d like to think—where we said so much in comfortable silence, and knew exactly what each other was thinking with just a simple look. Thinking back to that time when I was in our tiny town’s jail (it was for only two hours), my dad may or may not have given the deputy a couple of hundred dollar bills to keep his mouth shut—which is also illegal, right?

I shake off the memory and look back at Marnie. “Either way, I’m helping this dude and then ignoring his existence. This is my one and only good deed for the year. No more.” My tone is unconvincingly assertive.

Marnie erupts in laughter, tapping my head gently as she says, “You keep telling yourself that, Gremlin.”