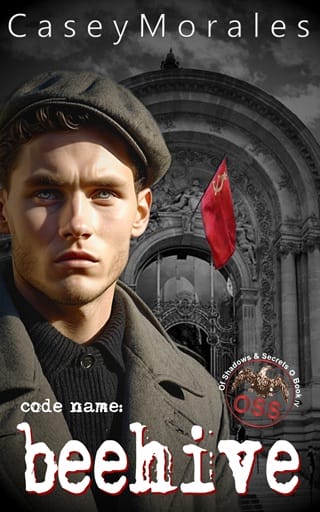

Beehive (Of Shadows & Secrets #4)

1. Will

1

Will

Present Day | May 1946

P aris was slow to wake, her arms stretching in the soft rays of dawn, casting a glow across the cobblestones. The French capital was the only place I knew where buildings shimmered like liquid sunlight.

It was unseasonably cool, even for a late European spring. Most still donned thick woolen coats, stylish hats, and fluffy gloves to shield from the chill. Colorful scarves encircled slender necks, as Parisians refused to let postwar struggles strip them of their sense of fashion.

It felt like I was walking through a dream. It always did here.

London was home when the war ended. Thomas and I celebrated with the Brits, laughing and dancing in the streets, raising glasses and, in some cases, whole bottles. For a brief moment, despite Hitler’s destruction that enveloped everything—and everyone—the topsy-turvy world in which we’d lived seemed to right itself.

I had hoped we could stay in London, see British children return from exile with their infectious laughter and watch as the grand old city patched its wounds and knitted itself back together.

Unfortunately, Uncle Sam had other plans for us.

Near the end of the summer of ’45, our OSS London chief called us into the Embassy and told us to pack our bags.

We were headed to Paris.

Our job was to quietly assist that city’s recovery while gathering intelligence on the presence of former Nazis who might be hiding in plain sight. As the station chief concluded his instructions, he added, “And keep your eyes open for Soviet activity. Uncle Joe has been restless lately.”

Thomas and I wrestled with exactly what that meant but were unable to fully wrap our heads around the meaning buried beneath the words.

Such was the life of a spy.

Our move from London to Paris flowed as smoothly as any postwar move could, and the French welcomed us with open arms. Given America’s role in helping free Europe from Hitler’s grasp, few days passed without hugs from elderly women or pecks on the cheek from younger ones. It felt a bit like being a celebrity without the stage or screen. I wondered if US soldiers stationed throughout Europe felt the same.

For a year, Paris stirred and rose, as if shaking itself awake from the nightmare of war.

Thomas and I ambled along Rue de la Montagne Sainte-Geneviève, the street damp from a light, early rain. Everything smelled fresh and alive. But it wasn’t just the city that felt different; we felt different, too.

Today, for the first time in forever, we had nowhere to be.

Side by side, we took our time, brushing shoulders as we walked, letting our hands drift close, fingertips touching but never quite lingering. For one brief moment, it felt like the world belonged only to us.

We passed vendors setting up for the day. It was only in the past few months that they had returned to Paris’s streets. Rationing had taken its toll. Fields were only beginning to produce for locals rather than foreign occupiers.

Fresh bread and pastries, their golden crusts peeking out from beneath cloths, filled storefront windows. Thomas tugged me toward a boulangerie with a grin. I laughed, knowing full well he had no plans of letting us pass without stopping. I left him standing on the street, a lopsided grin on his lips, as I darted inside to retrieve our treats.

Thomas stood in the cool air, chatting amiably with nearby patrons. He was the one with the charm, his bright-eyed enthusiasm drawing attention, and I didn’t mind fading into the background to watch him soak it all in.

His accent marked him as American, but that only added to his appeal. It might’ve been the resistance who struck the match and lit the flame, but it was the Allies who ultimately finished the Nazis off and freed Europe from their shackles—and the French people loved us for it.

“ Pain au chocolat? ” I asked, holding two warm, flaky pastries between us as I returned from inside.

Thomas took a pastry, his fingers brushing against mine. “You know me so well.”

He groaned in an almost vulgar manner as he took his first bite. A nearby couple turned, then broke into quiet laughter, the older woman covering her mouth despite her dancing eyes.

His gaze twinkled in a way that made my heart skip.

I’d seen him hardened by war and duty, but on that morning, he was just Thomas—the man I loved, with no shadows or secrets between us.

We continued our stroll, passing a few shops with their windows still taped up, reminders of everything that had befallen Napoleon’s great city. Here and there, a street sign gleamed with fresh paint. Walls bore faint marks where bullets had pocked the stone. Paris wore its scars like whispers, visible only if you knew where to look. It was an odd mix of sorrow and beauty, as though the city told its own story of survival.

I slipped my hand into Thomas’s and gave it a squeeze, finding comfort in his steady presence. Gays were not openly celebrated in France, but postwar weariness stole even the fundamentalists’ desire to bicker, allowing men and women who loved in secret to occasionally step into the sunlight. We hoped that progress would continue as the world put the horrors of hatred and war into the past.

We rounded a corner, and there it was—the familiar red awning of Les Bon Georges, a canvas forming a smile that warmed my heart as it flapped in the breeze. The bistro looked the same as it always had, tucked modestly between larger storefronts, its iron sign swinging gently in the breeze. Miraculously, the war had left this eatery alone.

Les Bon Georges was one of those places that looked like it had always been there, and for the resistance, it had been an anchor. George Creuset, the owner, had welcomed us, the bistro doubling as a safe house and a meeting point for fighters and operatives.

Today, though, we weren’t on duty.

Today, we were two men looking forward to a hot cup of coffee and a chance to catch up with an old friend.

A bell tinkled above the door as we entered.

George, a man with Hollywood good looks and a pencil-thin mustache to match, looked up from behind the counter, his eyes brightening.

“Ah! My American boys!” he boomed, his voice filling the room like the pounding of an orchestra’s timpani. “I was beginning to think you had forgotten me.”

I reached out to shake his hand, but George slapped me aside and pulled me into him for a hearty embrace and two quick pecks on each cheek.

“We could never forget you, George,” I said, smiling. “Besides, Thomas is unbearable without his coffee.”

Our old friend chuckled, clapping me on the shoulder before turning to Thomas. “Unbearable, eh? And here, I thought you were the level-headed one,” he said, shaking his head in mock disapproval. “Getting a bit soft on me? It must be the Paris air. You know it is sweeter here than anywhere in the world.”

“The air or the men?” Thomas grinned as he sloughed off his coat and took a seat.

“ My George would say both!”

George’s George, his lover of somewhere between a decade and a lifetime—he would never confirm which—was a singer at a local cabaret. Where our George was generally humble and demur despite his gregarious welcome and booming laugh, his George was the sun beneath which all life grew and flourished. His burned so brightly that most had to avert their gazes. It was impossible to not love the man, and he usually traveled with a posse of adoring fans.

The Georges were good men.

Les Bon Georges.

George laughed, disappearing behind the counter to return a moment later with two steaming cups of coffee. He didn’t need to be told how we took it—he knew us well. With a wink and a pat on my shoulder, he left us alone, but not without a knowing grin that told me he hadn’t missed the way we leaned close as our hands brushed beneath the table.

I took a sip and savored the warmth, letting the calm of the bistro settle around us.

Despite having not yet opened his store to the public that morning, George had opened the enormous glass wall that was his front window, allowing us to better watch passersby and enjoy the morning breeze. The café was a modest place, with mismatched chairs and the smell of fresh bread lingering in the air. It had a simple charm, like a relic of a Paris that managed to survive a war, perhaps many wars.

As I looked at Thomas across the table, I felt the weight of memories.

I was sure I always would.

But today they felt lighter, softened by the quiet warmth of George’s bistro. I reached for Thomas’s hand, our fingers linking. It wasn’t much, but that one slight gesture felt like everything.

“Remember that night here with George?” I asked, my voice low.

He chuckled, the rumbling sound warm and familiar. “Leaving here was hard, but it was the first leg in our first mission.”

“Are you saying that George was our first?”

Thomas nearly spat coffee across the table. I glanced down at my coat to check for splatter. “Don’t make me laugh. That’s a waste of the best coffee in Paris.”

I reached behind and grabbed a cloth napkin from a nearby table, then handed it to him. “Feels like a lifetime ago, doesn’t it?”

Thomas’s eyes softened, and he gave my hand a gentle squeeze. “It was, but we’re here now, and that’s what matters.”

We finished our coffees and said our goodbyes, then strode into the brightening day.

The beauty of Paris awaited.

We made our way along the Seine, and I found myself noticing the finer details—tiny buds pushing through cracks in the pavement, the faint scent of blossoms in the air, the way the bridges had been patched up with fresh stones that stood out against the older bricks. The city was healing, slowly, in ways that were easy to miss if you weren’t looking.

Oddly, it felt like a privilege to see it happening.

We paused by the Pont Neuf, leaning against the railing, watching the river’s lazy current. The Seine sparkled, carrying stories and memories from the past that Paris seemed to be releasing, bit by bit. A few boats drifted by, laden with supplies, their operators shouting greetings to each other across the water.

A few bore men in uniform.

Thomas’s gaze was fixed on the skyline, his face relaxed, softened by the sun. I let my shoulder press against his, our hands coming together in a quiet motion that felt both ordinary and extraordinary.

“It’s hard to believe this place was a battlefield only months ago,” Thomas murmured.

“And now it’s just . . . Paris.” My heart swelled with a strange, fragile hope. “And we’re here, together.”

Thomas turned and met my gaze, his eyes filled with a familiar warmth that had been there since the beginning, since our first days at Harvard.

“You’re right,” he whispered. “Just Paris.”

We continued along the river, taking our time, letting ourselves sink into the city’s quiet rhythm. Near the end of the day, we found ourselves back in the market at Rue Mouffetard, the sun casting long shadows across the bustling street. The vendors were still out, their stalls lined with fruit and bread, flowers and spices. Meat remained in short supply, but few complained.

A woman at a fruit stand caught my eye, her face lighting up as she pressed a handful of cherries into my hand. “Life is coming back,” she said, her voice warm, her smile knowing. “And love, too, I see.”

My cheeks flushed, and the woman’s smile grew. Thomas threw an arm around my shoulder. The woman chortled and clapped her weathered hands.

I thanked her, feeling my cheeks blaze, and offered a cherry to Thomas. He took it, holding my gaze as he bit into it, the smile on his lips both mischievous and tender. It was such a simple moment but held a kind of intimacy that made my heart swell to bursting.

As the sun dipped lower, again crowning the city in a soft golden light, we turned toward our flat, our hands brushing one last time. We wouldn’t be so brazen as to hold hands on the street near the place we called home, but an occasional brush was irresistible. I let myself lean into him, just a little, just enough to feel the warmth of him, to know he was there.

We turned down the final street toward our tenement, and Thomas froze.

“What is it?”

He stared at a building across from ours, and I followed his gaze.

My heart stilled.

Ten windows peered back from ten apartments.

Nine were blind, their curtains closed.

One winked, with one side closed and the other pinned up so the glass pane’s eye was half lidded.

Thomas turned back to face me and said, “Well, shit.”