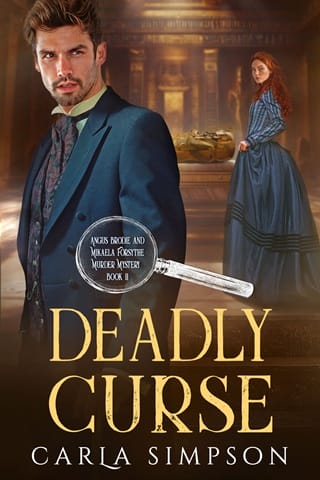

Deadly Curse (Angus Brodie and Mikaela Forsythe Murder Mystery #11)

Chapter 1

One

APRIL, 1892, LONDON

Spring had at last made an appearance across London. We’d now had sunshine three days in a row!

It was a record to be certain according to my great aunt, Lady Antonia Montgomery, as Mr. Hastings, her driver, maneuvered the coach through early morning traffic toward the British Museum.

Mr. Munro had convinced her to take the coach with the weather uncertain—he was after all a Scot, as well as her manager of estates and current caretaker of the open motor carriage she had purchased.

He knew a little about weather, that it could be stuamachd, he had explained in that broad Scots accent.

“Temperamental,” Brodie had translated as Mr. Hastings had arrived at the townhouse in Mayfair.

“A bit like a woman,” he added as he set off with the cabman who had arrived to take him to the office on the Strand and a meeting the current acting Chief Inspector of Police had requested.

I was immediately suspicious. There was no love lost by either of us when it came to the Metropolitan Police and past incidents. The most grievous, however, had been the actions of Chief Inspector Abberline, who had Brodie arrested and imprisoned under false charges in retaliation for a past incident when Brodie was an inspector with the MET.

If not for the intervention of Sir Avery Stanton of the Special Services Agency, he might have been hanged. Or in the very least, sent to Newgate.

Abberline—I refused to acknowledge him with any accolade—he was presently on indefinite leave over the matter. Interim Chief Inspector Graham was a man Brodie had served with and respected.

The indefinite part of Abberline’s departure should be definite , as far as I was concerned. He simply was not to be trusted, and I for one did not accept the formal apology he had made to Brodie over the whole affair. An old saying came to mind: leopards did not change their spots.

The weather did behave itself, as my great aunt commented, as we arrived at the museum. I didn’t bother to mention the clouds that steadily rolled in from the Thames.

Instead, I tucked both our umbrellas under my arm as we disembarked the coach at the main entrance, with those tall columns at either side and the overhead banner spread between that announced the opening of the newest addition to the Egyptian wing.

“Do ye want me to come with ye?” Munro asked as I slipped my other arm under my great aunt’s—not that she needed assistance.

She was hale and hearty and would undoubtedly outlive us all. However, she had taken to using a walking cane the past year after an “undesirable encounter,” as she put it.

It wasn’t as if she needed the cane for assistance with walking. However, it made an excellent weapon.

“Not at all, Mr. Munro,” she informed him as she tapped her way ahead. “It is not as if there is anything dangerous or life threatening in an exhibit of ancient relics and artifacts, not to mention a few dead people.”

Sarcophagi was more accurate, complete with the remains of mummies that had been publicized over the past several weeks as the exhibit approached completion.

“Aye,” Munro replied as he returned to the coach. “Mr. Hastings will return by the noon hour.”

“Do come along, Mikaela,” my great aunt said as she climbed the steps ahead unassisted. “This is most exciting.”

I caught up with her inside the main entrance. We followed other attendees to the Egyptian hall.

“I don’t believe I mentioned that I once entertained Sir Nelson’s father,” she added conversationally. “Quite handsome, but also quite the philanderer. However, we remained good friends.”

Entertained? Knowing my great aunt, that might include almost anything. I did not ask.

She had never married, although it seemed there had been no shortage of suitors when she was a young woman. As she explained it, she had simply never found a man worth giving up her single status, particularly as her father’s heir to the Montgomery estates.

“That whole thing about all my properties and possessions passing on to a husband,” she once said. “I never found one worth my time, let alone the family fortune. And it isn’t as if I don’t have a family of my own.”

As for having once entertained Sir Nelson’s father?

“Only once,” she explained now, which was more than I cared to know, as we approached the hall where the Egyptian room was located.

“That was enough. The man was quite inept.”

I did not inquire what that might mean.

With my great aunt safely escorted to the exhibit hall for the new Egyptian exhibit, I continued on to the office of Sir Nelson Lawrence, who was responsible for discovering the artifacts and then bringing them to London for the exhibit.

We had met previously when I was on an early adventure to Egypt while he was on his latest exploration and was to be spending the next several months there.

In recent years he had established himself as an authority on Egypt, its history and culture, and had brought back countless artifacts, including the present exhibit.

He was highly educated, and had spent almost twenty years in Egypt, yet not the usual sort one might expect … distracted, and somewhat aloof.

Instead, he had been most congenial, not at all put off by my endless questions, and even extended an invitation to visit the site he was returning to, to continue his work.

During that long voyage when we first met, he had taken on the unofficial position of travel guide, and continued once we reached Cairo for the handful of us who chose to venture into the Valley of the Kings.

He had written me several times after my return, and I found his updates on his latest pursuits fascinating. He had also written me before this latest return, along with a description of the artifacts he was bringing with him. I was looking forward to the exhibit, and eager to see him again and learn more about his recent travels.

His assistant, Mr. Hosni, informed me that he had already gone to the new room where the exhibit was to open that morning.

“You might find him there,” he explained in perfect Queen’s English.

We had not met before, but Sir Nelson had spoken highly of Mr. Hosni. He had been educated in London, and returned to Cairo with Sir Nelson on a previous trip and had been with him since.

He was soft-spoken, slender of stature, and wore a conventional suit, as I had seen many wearing when I was in Cairo, along with a turban. His beard was neatly trimmed, and that dark gaze reminded me of another. Yet there was a distinct difference in his hooded expression.

I thanked him and returned to the hallway outside the new exhibit room.

Guests had gathered in the saloon across from the room with the new exhibits.

“Good heavens!” my great aunt whispered as I rejoined her. “There is Louisa Ivers-Braithwaite. I thought she was dead and I had simply missed the announcement in the dailies. She might as well be, she doesn’t look at all well.”

Aunt Antonia did have a habit of speaking quite bluntly. She had once explained that at her age, she simply didn’t have time for proper social exchanges. She therefore had a tendency to be quite outspoken.

It did seem that Louisa Ivers-Braithwaite was intent on giving more than a mere nod in greeting, as she started toward us through the crowd as we waited for the exhibit to open.

I quickly removed myself and made for the refreshment banquet for a cup of coffee. I could only guess at their conversation as I watched their exchange.

As for Louisa Ivers-Braithwaite’s response to a comment from my great aunt, “Oh, my!”

I could only guess by the expression on her face, which suddenly changed to wide-eyed surprise and shock, as what little color she had drained from her face.

They were both saved any further exchange or shock, as a docent of the museum appeared at the entrance to the saloon and announced that the exhibit was now open.

“How is Mrs. Ivers-Braithwaite?” I inquired as I joined my great aunt.

“A dithering idiot. I am convinced that the world is a much safer place without her son adding to the population. I saw him not long ago. Put a gown and wig on him and one would not be able to tell them apart.”

We crossed the hallway to the entrance of the Egyptian Room and presented our embossed invitations to the docent. We followed the queue of visitors into the room, where we were greeted by young Mr. Howard Carter, whom I had met on previous explorations of the museum.

“I was hoping you would attend, Lady Forsythe,” he greeted me. “Knowing of your previous travel to Egypt, of course.”

We exchanged greetings, and I introduced my great aunt.

Although barely twenty years old, Mr. Carter had finally secured a position with the museum and planned to accompany Sir Nelson when he returned to Egypt.

“The exhibit is quite magnificent,” he commented. “I was able to assist in preparing it for today’s opening. I just returned from the museum director’s office. Do let me know if I can be of any help, or answer any questions.”

And he was off to make his rounds of the guests.

“Do let us see what Sir Nelson has brought back this time,” my great aunt commented. “Always fascinating to view the artifacts of other cultures. This should cause quite a stir with Sir William Flinders Petrie. Until now, he has been considered the foremost expert in Egyptian antiquities.”

I was aware of Sir William’s exhibitions over the past few years. He had acquired substantial backing for his ventures to Egypt and had presented those exhibitions in the Edward Library at the University College.

A rivalry between the two men had been promoted in the newspapers, and the invitation my great aunt had received spoke to that rivalry, promoting Sir Nelson’s exhibit as possessing the most extensive and important discoveries to be found in Egypt to date.

To say the exhibit was magnificent, was an understatement. Carved stone busts of ancient figures filled at least a dozen glass display cases, while a half-dozen enormous carved statues lined the walls between floor-to-ceiling columns. The craftsmanship, over two thousand years old, was remarkable.

Glass cases displayed a variety of ancient tools and weapons down the center of the room, each one with a label that described where it had been found and the purpose for it. Between each set of cases were ancient figures of animals on pedestals, representing various Egyptian gods that included two lion-headed goddess statues of Sakhmet, a bronze figure of a cat, the sacred animal of the goddess Bastet, and a statue of a jackal that represented Anubis, protector of the dead.

However, the central figure of the exhibit was a towering statue of Ramses II at the far end of the room.

As we awaited the arrival of Sir Nelson, the man responsible for bringing the magnificent exhibit to London, I stopped to admire a glass case with finely made tools and instruments. Some were claimed to have been used for surgical procedures according to the placard inside the cabinet.

I had learned in my travels that the Egyptians were fascinated with exploring the human body, which undoubtedly had led to the removal of human organs found in canopic jars. They had performed complicated medical procedures as well, according to ancient papyruses that had been discovered, including surgeries of the brain.

They were considerably more advanced than some of those who practiced what was referred to as modern medicine, excluding Mr. Brimley, of course, who had assisted Brodie and me in several of our inquiry cases.

We had been waiting for some time for Sir Nelson to join the exhibition, which seemed odd since Mr. Hosni had told me that he had already arrived for the new exhibit.

Always content to go exploring about on her own, my great aunt continued on ahead in the direction of the statue of Ramses II, when I suddenly heard her startled exclamation.

“Good heavens!”

My first thought was that it might have been another encounter with Louisa Ivers-Braithwaite, although I was quite confident she could handle the woman. And truth was, her exclamation was not one of impatience, but that of someone genuinely startled. And there was hardly anything that startled my great aunt.

Had she perhaps been taken with a health episode? At her age it would not have been unusual. Yet, this was my great aunt, who I was certain would live for at least another hundred years.

I rounded a display with a statue of Osiris, protector of the dead, as I heard a scream and, as I reached that impressive floor-to-ceiling statue of Ramses II, found Aunt Antonia comforting a woman who appeared as if she might faint at any moment.

It took me a moment to determine what had caused both women’s reactions. Then I saw the body that lay at the feet of the statue.

Blood stained the front of the man’s shirt, where a gold-handled knife protruded from a wound in his chest, and a vividly painted Egyptian funerary mask covered his face.

“I must say, not something one sees every day,” Aunt Antonia commented as shouts of alarm and other screams went out across the gallery as a crowd gathered.

I knelt beside the body and carefully removed the mask.

Sir Nelson Lawrence was very dead.