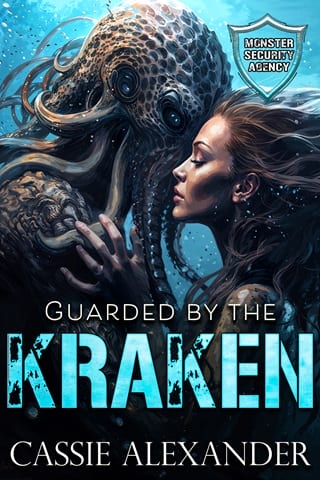

Guarded by the Kraken (Monster Security Agency)

Chapter 1

chapter 1

CEPHARIUS

A distant request came in from one of my kind, through the aqa like a tiny fish nibbling on the tip of an arm. I instantly responded, “No.”

The messenger wasn’t close enough for me to see, but sight was an often useless concept in the oceans we lived in. Waters could be choppy, or we might’ve swum too deep for light to reach. It was one of the reasons we relied on the aqa to transmit our thoughts, allowing us to communicate over vast distances, depending on the terrain.

“No? What do you mean no ?” the other kraken asked back, like he had no concept of the term—and by now I was certain his mind was unfamiliar to me.

“I mean no ,” I thought at him with intent, while considering which direction I should swim to stay out of his range.

I felt his confusion travel into my mind just the same as his words did. “You don’t get to say no when it’s the king asking.”

“You do when he’s your broodbrother.” In fact, when he’s your broodbrother, you can tell him to go pump himself. I was careful to partition that last thought off, though, so it didn’ t travel to him.

“But—” the unseen kraken began.

“NO!” I shouted at him, flashing red in the sea I hovered in.

The pod of endangered manatyls I’d been guarding had been ignorant of my presence until that very moment; krakens could be utterly still when they wished to be, controlling our buoyancy via manipulating internal structures. But in my anger I’d betrayed myself. All of the small herd scattered, swimming through the water in different directions with their large sweeping wings, and I clicked my beak in annoyance, which only frightened them off further. I closed my mind to the ’qa, unwilling to let anyone else’s thoughts in, in my vast irritation.

After Cayoni had passed, I’d swum away from my home on purpose, trying to escape the low-level thrum of everyone else’s lives. I’d taken this job with the Monster Security Agency in the frigid Upper Ocean protecting the manatyls because they weren’t entirely safe from humans, no matter what kind of treaties the two-legged kind signed with one another on their land, and I intended to keep doing it.

But . . .

I hadn’t even asked the other kraken why my brother had wanted to see me. I’d just protected myself from the sharp pain of my past on instinct.

What if Balesur’s mate had died? Or he was sick? Or, worse yet, Gerron?

The manatyls were slowly regathering in their protective formation. I hadn’t moved in the water yet, so they’d forgotten I’d existed.

If only the rest of my family could do the same.

I hovered in the middle of nowhere, halfway between the waves above and the ocean floor, thinking hard, while hiding my thoughts from the ’qa, lest another of my kind be near.

Which would I regret more? Briefly returning to the torment of Thalassamur, or discovering that I’d missed my chance to see a loved one one last time?

I raced my mind out along the ’qa and felt the weak flashes of thoughts the manatyl possessed—some were hungry, others were tired, and one eagerly lusted—but the kraken I’d shouted at was gone.

I’d had this assignment for three years. The two-legged above knew of me, and it would take a long while for their fear of me to subside.

For now, this pod was safe.

“I will be back,” I promised the broad-winged creatures, even though I knew they couldn’t understand me, then spun in the water, and started swimming for my home.

It took two weeks to travel from the cool waters I had been in to the warmer waters of my childhood, but I knew I was getting close when I could feel the loose, chaotic, and intrusive thoughts of other krakens.

“You will?—”

“Move!”

“A sharper hook?—”

“—don’t you agree?”

I slowed my swimming and clung to a rock outcropping covered in purple anemone and orange sea fans that furled and unfurled with the current, trying to deal with my emotions before I was discovered.

Until then, I pretended to be like a piece of kelp, letting the current gently rock me, and once I’d accomplished that, managing to keep the thoughts of all of the rest of the krakens out of my mind, I let go and started swimming again, cleaving to the shadows of the outcroppings of rock and coral that created the broad road of sorts that led into my kingdom, my city, my home.

It would take any kraken a day to swim across Thalassamur—which didn’t matter much, because every kraken in it could think at almost any other, and if your thoughts weren’t strong enough, if you were old or infirm, or if you needed to talk to many krakens at once, there were plenty of skilled countrymen who could act as amplifiers, shouting your message for you across the ’qa.

I avoided every kraken I could, sensing them far before they could sense me, doing my best to imitate the land around me, swimming in slow silence and getting my bearings—because every time you visited Thalassamur, it had changed.

It was almost impossible to create structures that could survive the ocean’s inexorable flow, and so few truly tried. Most kraken just had patches that they tended to, that they understood to be “theirs”, inasmuch as they could feel the thoughts of anyone coming upon them, and they built whatever home they found most pleasing at the time. Some didn’t build at all, others belted themselves to stones each night so they wouldn’t float away, some dug pits and breathed through sand, others lived in caves, created cairns of stone, or claimed vertical territory along steep walls.

But certain krakens attempted to create something real.

Some of few took their time and chiseled out pieces of living rock and carefully placed it, stone over stone, until they’d crafted the perfect home for their mate over years, building a place both tame and wild, as only the best gardens could possibly be.

And then one of those krakens discovered when they’d returned from their hunting party that their beautiful mate had been crushed beneath the stones they’d so lovingly arranged to shelter her, because she’d been unwilling to abandon their precious egg in the middle of an undersea tsunami.

Tsunamis were what the two-legged called them—something I’d found out when I’d been forced to interact with humans as a child.

Krakens called them the Killing Wave because of what they did to the sea floor .

And I knew if I thought on it for one moment longer I’d be found?—

“Cepharius?”

Another mind touched mine. I pulled in all of my sorrow like an eel pulling back into a burrow, trying to hide myself, but it was too late.

“Cepharius!”

And once my name was on the ’qa, there was no way to take it back.

“Cepharius is back!”

“Who is Cepharius?”

“Balesur’s brother!”

“Madron’s child!”

I felt myself pummeled with thoughts and joys and curiosity, and it took all my strength not to turn and swim back into the open sea.

“Please, stop,” I thought out in all directions. “I am only used to solitude.”

This did nothing to abate my countrymen.

“Shhh—”

“Leave him alone.”

“Everyone be quiet!”

“I am!”

“Stop saying things! He wants us to be?—”

“Cepharius.”

One sweet and calm thought cut through all the rest, quieting them instantly. Balesur’s mate, Sylinda, and I felt her mind flow towards mine along the ’qa. I focused on her at once, shutting out all the rest as best as I was able.

“Are you well?” I asked her. Her thoughts were not tinged with sorrow—so Balesur was alive, and their child too—which meant that I could go.

But then she found me in person, coming up from behind a mound of porous rock. She waved a hand at me in recognition, as the rest of her long tentacles swept beneath her in a calming blue. She swam up before I could retreat.

“Are you?” she asked of me in return, hovering just out of touching range.

I didn’t dare answer her.

I knew how the two-legged communicated above, with their words that traveled through air, with voices and how they were unable to hear one another think or to truly know one another’s feelings.

This was how they were able to easily lie, whereas for the most part, my kind could not.

“Let us talk where it is more quiet. For you,” she said, providing me with a graceful exit and then I had no choice. She turned, and I was forced to swim beside her.

Sylinda cut a magnificent swath through the waves, bunching her lower-arms in and swirling her mantle between them as she pushed them back out, jetting herself forward and not giving me a chance to do anything but follow.

I recognized the path we were taking though. To the center of Thalassamur, where the most formal of the structures were, a series of lava tunnels with ceilings that time had worn down to have large gaps in them, so that light could pass through.

I could hear the thrum on the ’qa of everyone reacting to my presence, so I knew news of my return had preceded our entrance to the central throne room. It was a large open cavern, filled with life and other krakens, many of whom were leaving after Sylinda sent them a request to depart.

They stayed long enough to see me in person though, and I didn’t need to wonder about their thoughts.

“Where has he been?”

“Poor Cayoni?— ”

“—their egg?—”

And this was why I’d left.

I felt anger rush inside me, as I clenched my beak and scowled with my lips above it, the short tentacles that framed my face clutching one another in my fury, until a high-pitched thought crashed into my mind.

“Uncle Cepharius!”

You couldn’t hear the thoughts of children until they were within a body-length of you or so most times, which allowed adults the chance to be adults, and our young the chance to be innocent, without growing up in a stew of other people’s opinions of themselves and others.

But Balesur’s son, Gerron, was close enough for me to hear him now, as he raced into the room to meet me, his entire body an elated pink as he bounced around, making excited gestures with his upper arms and hands, while his lower-arms shot him from place to place in speedy squirts while squealing.

“Where have you been? Why haven’t you visited? Why didn’t you take me?”

His thoughts crashed into mine, and I realized the second reason kraken children couldn’t join the ’qa until they hit their breeding age—because most of them talked far too much, and were far too loud. If Thalassamur’s ’qa let children into it, we’d never hear the end of them.

“I was working,” I told him, twisting my neck to keep an eye on him as he zipped about the room. I could sense he didn’t believe me. He finally slowed and made a disappointed sound. “Far away,” I went on. “Guarding manatyls.”

“Why?”

I huffed, trying to come up with an answer that would make sense to him, without bombarding him with my sorrow.

“Because he had an important job to do,” Sylinda cut in, saving me from myself. “It is a trade we make with the two-legged for certain information. ”

That part was true at least. I was one of the few krakens that had willingly had contact with the outside world.

“But manatyls are stupid,” Gerron complained, and he wasn’t wrong.

“They are dense creatures, to be sure. But they deserve to live, same as any other.” And to not be hunted for their meat, which certain unscrupulous two-legged above believed had magical powers, a thing that I knew to be manifestly untrue. I contained more magic in one lower-arm than a manatyl did in its entire body, but the two-legged didn’t need to know that.

Gerron wove back and forth, clearly holding something back, and I was proud of him for managing to keep it from us—he was growing into his abilities, and a few years more he’d be ready to join the ’qa. As it was, either Sylinda or I could’ve upended his mind to make him tell us what he was hiding, but that was not our way.

Then finally he confessed. “You didn’t leave because I broke your statue?”

I blinked.

“No, of course not. How many times have I told you that?” Sylinda said, close enough to hear us and answer for me.

“I just needed to be sure!” Gerron shouted at her, then hovered in the water between us, anxiously winding his lower-arms.

“What statue?” I asked, while questing with my thoughts.

Sylinda sighed on our connection. “The one your grandfather had carved, of you and Balesur.”

Gerron took a moment, staring at me, before flaring red and shoving anger across our ’qa, then turning to flee the room, all eight of his tentacles spiraling behind him.

“Gerron!” Sylinda shouted after him. “Don’t be rude!”

I was terribly confused. “I could care less about that statue.” My visit to Thalassamur was not going well.

“You left right after,” she said, turning back to face me, her own colors going dark. “He’s been obsessed, thinking that’s why you disappeared, ever since. ”

“I didn’t even know it was broken.” Not that it would’ve mattered to me besides.

“Oh, I know,” Sylinda went on. “Because to have known, you would have had to come home, and tell us why you volunteered for your assignment.”

I curled some of my lower tentacles in frustration. “You know why I left?—”

“And you didn’t say goodbye!” The shades on her skin, which had been so cool and calm prior, now flashed angry patterns of maternal rage. “What was Gerron to think? That he didn’t mean anything to you? Or your brother? It would’ve been better that you had left because of a statue than for him to know the truth.”

I clenched my beak, rather than respond to her. I was one moment away from letting all the pain I felt over Cayoni’s death pour out onto the ’qa and if I started, I didn’t know if I’d ever be able to stop.

But then the patterns streaking across her skin slowed. “Didn’t you know I also missed her?” she asked, and that was somehow worse. “She was like a sister to me—and then I lost the two of you, both at once.”

Sylinda reached for me with her hand, and I pushed back in the water. I knew if I touched her skin on skin, I would be flooded with her thoughts. Physical contact was even stronger than the ’qa, and I knew that she was hurting; I could see it in her eyes.

I could barely stand my own pain. I could not take on another’s.

“Cepharius!”

I felt my brother’s mind as he finally caught up to us, entering the room with broad strokes of his mantle, and I looked him over for fresh scars. The lower-arm he’d been missing after a battle we were in when we were younger had fully grown back, and nothing new marred his hide.

So why was I here?

“You came!” he went on—and I realized at that moment that he hadn’t been sure that I would .

“I did,” I said. He swam up to me, the same as Sylinda had, and I, again, swam back.

I could feel his sorrow at my instinctive response. His thoughts had become more sonorous since I’d seen him last, like the responsibilities of being the ruler of all our kind had weighed on him.

“Are you so set on never touching a kraken again?” he asked calmly, his tentacles drifting beneath him in the stone gray of determination.

The last kraken I’d touched had been Cayoni, after her death, three years ago—and I’d been avoiding physical interactions with sentient creatures the entire time since. “I have no reason.”

He briefly took on a knowing look. “Then you won’t mind me reassigning you.”

“Balesur,” I began, swimming back even further, to begin my escape, as he continued.

“We need somebody to touch a human.”

My entire body flashed red at once. “No.” But his mind took on the inflexibility of the rock surrounding us. “I will not,” I said, emphatically.

“You will,” he disagreed. “Because the same two-legged who gave you your job out in the cold Upper Ocean has requested our services again.”

The red on my skin began pulsing, and I was only barely controlling my anger. “Find someone else.”

“No. He asked for you, personally.”

“Pump him!” It was the rudest comment one of my kind could make. “I don’t want to?—”

“I’m not asking as a brother. You’re doing as your king commands.” His skin flushed the same color as mine and he thought at me hard, before looking to his mate. “Syl,” he said, and she swam to be between us quickly.

Sylinda was an amplifier—but she was also capable of sensing other krakens on the ’qa at great distances. “We are alone,” she thought out to the both of us.

My brother’s red tone only increased. “They want you to guard a human scientist at a research facility they’ve created on the bottom of the ocean, inside the Kalish Trench.”

I’d swum over it before, of course, but all krakens knew that past the first few thousand feet down, trenches were desolate and deadly places, suitable only for creatures that could sense prey in the dark. I couldn’t imagine humans managing to live there—but I’d also interacted with enough humans to know I shouldn’t put anything past them.

And in the end, it was my curiosity that doomed me. “The very bottom?”

Balesur nodded solemnly.

“Why?”

“I do not know. They asked permission before doing so, of course, and I granted it, with strict limitations—no mining, no nets, none of their ridiculous pipes or cables—thinking that would scare them off. But it didn’t, and they decided to build it anyways. We watched them to make sure they were honoring their word, and they have been, but they are clearly up to something. We haven’t been able to figure out what it is they’re doing, or if it is important to us. But now—we have this opportunity.”

As did I, I realized—to free myself for good. “And I must be the one to help?” I pressed, cornering him as much as myself.

“The two-legged asked for you in person. He’s been floating on a boat above us, waiting for you to return for the past two weeks.”

“And what were you going to tell him if I didn’t show up?”

My brother shrugged. “I would’ve sent someone else up there. We all look alike to them.” I could feel Balesur’s dark humor on the ’qa between us. “You haven’t been home in years, Cepharius.”

“And all this time, you’ve just been looking for an excuse to recall me.”

“To bring you back to your family, and your duties.”

“Which include sending me away, again? To the bottom of a trench, to touch a human?” I gave him a mad laugh .

“Because I trust no one else.” His colors shifted to a deepwater blue, trying to soothe me. “You have the skills, you’ll have the opportunity, and I know you will come through.”

Sylinda hovered nearby, listening to our thoughts no doubt. I felt a wave of her sorrow over Cayoni’s death pass over me, as she felt me think of her, and I had a dreadful realization before I returned my attention to my brother. “But mostly because I have no one else here that I care about. No one I would be tempted to leave my post for. And I am used to living without the ’qa.”

Balesur reached out to me with an arm and tentacle both, and I swam further back. “Those are your thoughts, brother,” he protested. “Not mine.”

“It doesn’t matter, when I know them to be true.” I looked up through one of the many holes that allowed light to shine into the cavern. It would be night soon, when the crystalkrill dove, and the amberdines rose to take their place, participating in the circle of life that happened again and again in the sea.

I wanted out of it entirely.

“As you wish, brother,” I said, making the colors of my skin match his own. “But after this, promise me you will not call for me again. I will go back to the Upper Ocean and do as I please and I will never rejoin the ’qa.”

“Cepharius!” Sylinda said, swooping as close as she could without touching me. “You do not mean that!”

I stared over her shoulder at my brother. “Do you swear?”

If whatever the two-legged were doing at the bottom of the trench was this important to him, it was the least he could do for me—to promise me the freedom to feel my pain alone.

“I do,” Balesur said.

“No!” Sylinda shouted at the two of us, but it was too late. Both of our thoughts were on the ’qa and there would be no taking them back. I would do this onerous task and then be free of my obligations forever after .

Sylinda shot away, propelling herself out of the room in a purple streak of pain and frustration.

“The two-legged expects you near the air at noon tomorrow. Your old bedroom is free; be sure to get up early enough to rise safely.”

“You already sent messengers ahead?” I was surprised and then irritated, that he had been so sure of me.

“I already told you. If not you, I would’ve sent someone else up to pretend,” Balesur said with a snort, before coming carefully closer. “How are you, Ceph?”

“Don’t ask,” I snarled, and then relented as I felt his concern radiating from him. “Please. Don’t.”

He shook his head again. “You have been alone too long, Cepharius. Your mind feels feral. And,” he began, paused, then decided to finish in a rush, “you do realize you’re not the only one this tragedy has happened to?”

I roiled in the cave, ready to swim out and hide in my childhood room, where at least I could pretend not to hear anyone. “Your wife hurts too, I know?—”

“No, not that—I mean, yes, obviously—but there are other mateless kraken, you realize? You could talk to them.”

“I would prefer not to.”

He puffed himself up like he would when we were younger and he wanted to be in charge. “That’s your problem, Cepharius. You’ve always been stubborn. And you never wanted to take chances.”

And Balesur’s problem was that he never realized I didn’t want the life he led. He had been groomed to rule, ever since he’d hatched, whereas all I’d wanted in life was what I’d had and lost.

When I didn’t respond, he deflated some, giving in to whatever tenor our relationship had now.

“Go out tonight, brother—if for no other reason than because your pumping arm must be the weight of an anchor. Use this opportunity at home to find someone to put it in before tomorrow. Release some stress and pressure before this mission. ”

“There is no need, brother,” I said, in the exact same tone that he spoke to me. “All of my stress and pressure will be gone the second this mission is finished.”

He took a long moment to stare at me. “As long as you are happy,” he said, and swam away, leaving me alone in the cavern just like I’d always wanted.