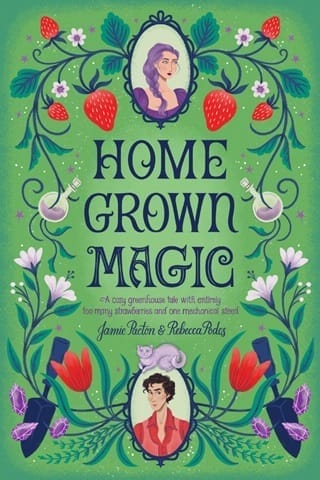

Homegrown Magic

Chapter 1 Yael

1

Yael

This party is supposed to be for Yael. So claimed the coveted invitations, heavy in their goatskin envelopes, thick paper addressed in malachite ink to the cream of society: Mr. Baremon Clauneck and Mrs. Menorath Clauneck request the honor of your presence in celebration upon their child’s graduation from Auximia Academy. But it seems to Yael like any other company event. The jeweled suits and gowns. The deals being made around fountains of pale champagne and velvety red wine. The offering altar tucked inside a private chamber off the ballroom—one of half a dozen such altars scattered about Clauneck Manor, this one meant for guests to curry favor with the family’s patron. It’s nothing Yael hasn’t seen at a thousand such dinner parties.

They weren’t even consulted on the cake flavor. ( Hibiscus, for fuck’s sake!)

“Let me guess. Animal handling?”

They look up from sniffing the ten-tiered monstrosity of a cake on display and find Alviss Oreborn smirking at them over the lip of a massive silver tankard.

“Come again?”

“Your field of study at Auximia. Animal handling, wasn’t it?”

Oreborn is teasing, clearly. He likes to pretend to be salt of the earth, the way he carries that tankard—albeit engraved with his own family crest—strapped to his belt like a shortsword and stomps around in mud-splattered boots even though there isn’t an unpaved street in the capital. Not south of the Willowthorn, at least. But Oreborn is a major depositor with the Clauneck Company. His silver mines are used to mint half the coinage in the kingdom—mines he hasn’t set foot inside for decades.

“Law,” Yael corrects him, pausing to drain their third glass of champagne, “with a specialty in arcana and transmutation. Father’s putting me in the currency exchange department at the company, apprenticed to Uncle Mikhil.”

“Well now. There’s a fancy job that’ll take you to many foreign shores.”

“I’m not sure it’ll take me any farther than the Hall of Exchange or the Records Library.” Yael grimaces, picturing the airless, echoing library in the bowels of the Clauneck office in the Copper Court.

If one were to gaze down upon Harrow from the back of a great eagle, the kingdom’s capital city of Ashaway would be easy to spot by its black basalt walls, roughly hexagonal; by the deep silver slice of the Willowthorn River, which runs from the mountains of the Northlands down to the west coast, carving right through the capital on its way; and, perhaps most of all, by the triumvirate of shining courts at its very center. The Golden Court at the topmost point, where the queens’ palace sits. The Ivory Court, home to the campus of Auximia, with its white stone towers. And the Copper Court, the main trading square in Ashaway—and thus, in the kingdom—named for its copper-tiled rooftops that blaze like bonfires in the sun. The Clauneck Company office is the tallest of the court’s fiery towers, but the library where records of every deposit, withdrawal, exchange, and investment are kept, accessible only by Clauneck blood, sits well below the earth. Its door is more thickly painted with security wards than the royal toilet.

“When you’ve seen one shore, you’ve seen them all, ey? Anyway, I expect you’ll be occupied by the family business, as well as the business of family making.” Oreborn claps Yael hard on the arm, and they almost fall sideways into the cake stand. “It’s the same for my Denby. See him yonder? Grew up handsome, he did.”

Yael looks across the ballroom at the towering Denby, shaped like a barrel with a beard. At twenty-three years of age, Yael has accepted the probability of staying five feet and a handbreadth tall forever…or mostly, they have. They’ve added a few inches this evening by fluffing up their finger-length black hair in defiance of gravity and the gods themselves. “Quite a specimen,” Yael manages.

“Isn’t he? I’ll bring him around in a more, er, intimate setting and reacquaint you two from when you were small,” Oreborn says with a wink. “Well, smaller.” Then he claps Yael again, roaring with laughter as he swaggers off.

Massaging their arm through their dress coat—green silk so thickly embroidered with ferns, buds, and briars, it’s stiff to move in, with a matching vest beneath—Yael watches Oreborn go. The man is a menace, and his son is a bully. They imagine having to talk to Denby, having to dance with Denby. It’d be like a squirrel waltzing with a big, mean tree.

Rather than consider it further, Yael makes their way to the bar counter to reacquaint themself with something stronger than champagne.

It’s only a moment before one of the barkeeps hired for the night notices them and approaches the counter. “Something to drink, sir’ram?” She pulls a glass from thin air in a flourish of magic, without anything like the scent of ozone and iron that accompanies the Claunecks’ own limited spellwork. A natural caster, then, of which there are none to be found in Yael’s family. Truly, magic doesn’t care whether you’re born into a manor house or a hut in the Rookery.

Yael watches, mesmerized by the muscled forearms beneath her rolled shirtsleeves. “ Everything to drink, if you please.” They grin and prop their elbows on the counter, their chin on one fist. “Where do you suggest I start?”

“We’ve a fine Witchwood Absinthe. Folk say you can hear the voices of the dead if you drink enough. Or perhaps a Copperhead. Ever had one?”

Yael flicks their eyes to the barkeep’s cinnamon-colored braids.

Flushing beneath matching freckles, she laughs. “It’s an ale with a shot of whiskey and just a few drops of snake venom.” She leans forward conspiratorially. “Most only feel a little numb in their fingers and toes. There’s a slight chance of paralysis, but that wears off before the liquor does.”

“Sounds like a quick ticket out of a boring party. I’ll take it, if you promise to drag me behind the counter where no one can step on me should things go sideways.”

“I think I can manage that.” With a wink, she turns toward the back bar to collect the necessary bottles and vials.

How times have changed. When Yael and their friends were children, they would creep out of the manor house to beg the stable hands for a few sips of whatever they were drinking; even Yael couldn’t have sweet-talked the barkeeps into serving eleven-year-olds in front of their rich and powerful parents. Though sometimes, Yael could distract one long enough for Margot Greenwillow—a natural caster herself—to send a spectral, shimmering hand floating beneath the bar’s pass-through and steal them a bottle. But those days of running wild around the outskirts of parties are long gone. Their childhood pack has scattered. Some have left Ashaway as fortunes and alliances shifted. Some, Yael’s lost track of altogether. Margot’s family was omnipresent in high society before Yael left the city at thirteen for boarding school in Perpignan—Harrow’s closest neighboring kingdom—and when they returned for college, the Greenwillows were simply gone, the best friend Yael ever had along with them. Impossibly, others are settling down and starting families of their own.

Oreborn was right about that much.

Yael’s parents looked the other way during their teen years at boarding school and during their time at Auximia, spent stumbling between alehouses, drinking and dicing with the children of judges, archmages, and princes. Nights like those were half the point of the kingdom’s premier school for noble and wealthy households. Even the months Yael’s just spent abroad in Locronan after graduation, traveling with peers who couldn’t bear to end the party yet, were begrudgingly permitted. But unlike many of their peers, Yael is no closer to marriage now than when they left for school. Baremon might have overlooked their mediocre grades and blatant disinterest in both law and the family business if they’d put as much effort into findinga suitable match as they had into spending their allowance and slipping beneath their peers’ silken bedsheets. Alas, they had not.

While Yael waits for their drink, they glance out across the ballroom in its gleaming glory. Thick marble pillars rise from an ice-white floor so highly polished it reflects the gold stars inlaid in the midnight-black ceiling above. (If this were a dancing party and not a drinking party, it’d be a slippery death trap.) Thousands of candles in crystal holders have mirrors placed behind them to scatter the light, which ought to give the room a warm glow. But the flames burn cold purple, thanks to a spell many children can manage—even Yael, so long as they’ve beseeched their patron recently, which they have not. In the corner, a quartet of musicians play their violins and cornets as quietly as possible so as not to drown out the guests’ wheeling and dealing.

Yael’s uncle Mikhil seems to be engaged in said wheeling and dealing with another figure from the Copper Court—some high-placed peddler of rare items “discovered” by hiring adventuring parties to traipse across the kingdom, even across the seas into Perpignan and Locronan and beyond. Mikhil has his wife on one arm, husband on the other, and a pack of Yael’s young cousins circling the trio like an obedient moat. Araphi, their oldest, stands among them, listening politely to what must be an excruciatingly boring conversation between businessmen. Their closest cousin in age, she’ll be going back to Auximia for her fourth and final year this autumn. As a child, Araphi was beautiful and unserious. She’s beautiful still, with dark eyes and a delightfully aquiline nose, shining in her silver-and-periwinkle gown cut high in the front, with matching, closely tailored trousers beneath. Whether Phi’s outpaced Yael in seriousness, they’re not sure.

It isn’t a high bar to clear, they acknowledge.

When the barkeep sets a glass of a swirling, dark-gold drink on the counter in front of them, they take it gratefully. “To my health,” Yael says, raising the glass.

It never makes it to their lips.

Snatching the drink from their hand, their father holds it just out of reach as he sniffs its contents and frowns. “In your haste to embarrass your family, I don’t suppose you stopped to think about this lovely young barkeep, who—had she injured you, even if by accident—would’ve been dismissed from her job, then run out of Ashaway at swordpoint? You never do stop to think, Yael.”

The barkeep’s mouth trembles, her freckles the only color left in her chalk-white cheeks. She stutters an apology, dips her head, and slips away as soon as Baremon’s turned his attention back to Yael.

They mumble, “I wasn’t going to—”

“Tell me, Yael.” Baremon holds the glass higher, as though inspecting the clarity of the poison. “Who is the heir to the kingdom?”

This is a bit much. Yael may not have been a model student, but they are at least aware of the royal family of Harrow, as is every child old enough to eat solid foods. “Princex Sonja,” they answer dutifully.

“That’s assuming the queens rule the kingdom.”

Yael swallows a deep sigh. Clearly, their father has set them on the path to their own humiliation, and now they’ve no choice but to keep walking. “If not the queens, then who?” they ask blandly.

Baremon seems unbothered by their lack of curiosity. “Ask anybody in the Golden Court, and they’ll claim that it’s the seat of power in Harrow. Ask anybody else in the kingdom, and they’ll tell you the Copper Court is where true power lies. And who is the king of the Copper Court?”

“You, I assume.”

Baremon glares down at Yael. “Precisely. We Claunecks are the uncrowned monarchs of Harrow. Lenders to queens, cousins to the highest judges in the land, keepers of the keys to this country’s economy. Nothing moves in the kingdom without flowing through us and the Copper Court, like blood through a heart.” As he speaks, Baremon’s eyes light as coldly purple as the candles throughout the ballroom, and the old, familiar smell of ozone and iron crackles around him.

Not natural magic, but Clauneck magic.

Just like fresh water or fertile soil, stone or sand or any other resource, magic exists in Harrow and the world beyond its borders in natural deposits. But instead of occurring in lakes and beneath fields, it occurs in living things, beasts and plants and people. In some of them, anyhow. While every life-form is, like a bottle made of cellular stuff, capable of containing magic, only some are born full up. Others, like the Claunecks, have the barest drop in the bottom of the bottle. It’s been three generations since a natural caster—folk born brimming over with magic—married into the family. Such people are increasingly rare in a world that has largely moved on to silver and gold.

Still, like the metal at the bottom of Oreborn’s deep-delving mines, magic can be found or borrowed or purchased for a price.

For folks who lack natural abilities but wish to cast anyhow, that means securing the favor of one of the deities or devils who exist in the planes beyond theirs, from which magic leaks into this plane. Those who work as healers may whisper a prayer to a god of health or medicine. A bard—a true bard, not just a common player in a tavern—may sing their prayers to a god or devil of revelry, hoping to please them in exchange for a bit of magic. Warlocks, on the other hand, make bargains. The Claunecks pay regular homage to their patron, fulfilling promises and performing tasks that increase his influence in the world, assuring his prosperity in exchange for magic they wouldn’t have otherwise. This is the family way.

Generally, Yael’s family prefers to speculate in stocks and bonds over spellwork, but they still rely upon their patron. And if the “offerings” their guests and customers leave on the altar happen to benefit the Claunecks financially? Well, their patron’s fortune and glory will inevitably rise alongside their own.

“And you,” Baremon continues his lecture, “are heir to the true power in this kingdom. You, Yael, are alas the only seed that I and your mother have sown.”

“Uncle Mikhil has plenty of—”

“But you are ours, ” their father cuts in, voice sharpening to a dagger’s edge. “And if you fail to produce, our efforts will have been for nothing. Can you understand that much, at least?”

“I…I understand.”

“Then see that you remember it and behave accordingly.” Finished with Yael, Baremon turns and strides to the center of the floor, where he booms out, “Friends, colleagues, I bid you welcome! Dinner will begin shortly, but first, a toast.”

Every eye in the ballroom turns his way.

Baremon Clauneck is…well, everything that Yael is not. Tall—or taller, though the man is no Denby—and impossibly sharp in his pressed suit, stitched to resemble bronze and black dragon’s scales. Somber. Square-faced. Sure of himself far beyond the film of false confidence that Yael wears at all times. And, as always, in total control. “To the future of the company,” he says. “To the future of the family. To us.” He hoists the Copperhead and drains it down, probably believing himself too important to be felled by paralytic venom. He’s likely right. Wiping his lips, he says almost as an afterthought, “To Yael.”

“To Yael,” the vast ballroom full of clients and associates of the Clauneck Company echoes. None of them tear their eyes away from Baremon to find Yael in the crowd. A good thing, since nobody notices as they slip out through the towering purpleheart wood doors into the corridor and disappear.

Because the grand ballroom sits on the third of six stories, it takes a full quarter of an hour for Yael to make their way out of the suffocating manor house and into the chilled air of a late-winter twilight. The ornamental gardens and the aviary are likely occupied by guests pretending to care about cold-blooming flowers and winged things, so Yael heads for the stables. With the party well under way but far from over, they find it blessedly empty of people.

Instead, it’s stuffed to the rafters with mounts from across the realm. Horses from the southeastern Swamplands, saddled with moss mats and bridled with vines. Sleighs from the civilized fringes of the Northlands, each pulled by half a dozen icy-eyed Laika. In one stall, a giant salamander—a dappled, poisonous-looking blue-and-gold beast—has its bloody snout buried in a ten-gallon bucket of mice.

The stable hands are probably sitting around a barrel fire out back right now, just as they used to, sharing their tips and a bottle among them. Yael would love to join them, hiding out until the dinner is over and the guests have departed.

But Yael has responsibilities. They have obligations. Their parents have been crystal-clear on that since the moment Yael returned from their travels.

Having floated through the academy on charm and the currency of their family name, Yael will now begin their meaningless job at their grand and meaningless desk in the Copper Court. Soon enough, there will be a meaningless political marriage with a partner approved by (or more likely, picked by) the Claunecks. Someone like gods-be-damned Denby. They will be expected to acquire children one way or another, and the children will be raised as Yael was: in a never-ending cycle of family duties and company parties, where they’ll perform for guests as Yael once did, then be tossed off into the shadows until they’re old enough for obligations of their own.

Suddenly, the air in the stable is too thick to breathe.

Yael tugs at the collar of their shirt, their vest, their dress coat, untucking and unbuttoning until they can gulp down the smell of sweating beasts and hay and blood. Which, in company with the wine and champagne, begins to feel like a mistake. Behind them is the manor and its ballroom, so they stumble toward the far end of the stable, bracing themself against support beams and stall doors as they go.

Until they grab for a door that swings open, sending them tumbling into the stall.

When they prop themself up, they’re eye to pupil-less eye with a gleaming mechanical steed. The horse stands statue-still, as you might expect from a creature made of hardwood and iron, polished like starlight for the occasion. Its brass kneecap is cool when Yael grabs its leg to hoist themself off the stable floor. The levers arranged in a mane-like crest down its metal spine have been switched off; with no need for food or water, the steed was powered down upon stabling. Probably it belongs to Oreborn, who keeps a small herd of them on his estate. He taught Yael how to ride years ago—or rather, taught them to canter around the paddock by themself while Oreborn discussed potential investments with Yael’s parents. Mechanical steeds are remarkable inventions. Yael could ride this one all night and day without stopping if they wanted to.

They won’t, of course.

They’ll brush the hay from their coat and leave the stable. They’ll pass the next few hours avoiding their parents when possible, laughing at jokes with cruel punch lines when they must. Tomorrow, they’ll crawl out of bed to share a silent breakfast with their parents. After a compulsory stop to pray at their patron’s altar—an act that more closely resembles checking inwith one’s coldly unpleasant boss for a performance evaluation than any kind of religious devotion—they’ll head to the office with their father. They will become who they were born to be.

Then Yael will just…continue to float through.

This is the plan. This has always been the plan.

So Yael is shocked to find themself astride the mechanical steed, having climbed up its body without meaning to. They remain surprised even as they thumb the correct levers upward, remembering their lessons. First lever raises the head. Fourth lever starts its heart, driven by some combination of magic and machinery. Sixth opens the valves for the heart to pump fluid through its armored limbs. And so on. Running their fingers over the steed’s iron neck, they brush across the engraved nameplate and bend forward to read it.

“Want to take a ride, Sweet Wind?” Yael hears themself slur as if from afar.

They walk the beast out of its stall, steering clumsily at first so that it weaves toward the stable doors. In their immaculately tailored pants and dress coat, they ride out onto the garden path, where they must admit that, planned or not, this is actually happening.

“We should go back,” Yael tells Sweet Wind.

They flip the lever up from Walk to Trot.

When, moments later, they reach the private lane connecting the Clauneck estate to the Queens’ Road, Yael promises them both, “Just a quick ride, then we’ll turn around.”

If they head north toward the city’s center, they’ll pass a dozen grand estates with sprawling grounds (though none so much as the Claunecks’) in an otherwise tightly packed capital, where land comes at a higher price than almost anyone can pay. Next, the ring of fine mansions without land to claim, then the plazas containing the Ivory Court, the Copper Court, and the Golden Court: the triumvirate at the heart of not just Ashaway but Harrow itself, surrounded by fancy shops and luxurious taverns and gilded offices, according to each plaza’s specialty. Northward still are the factories and workshops bordering the Willowthorn River. On its far shore is what people call the Rookery—the mass of crowded neighborhoods that make up the top third of Ashaway, with small, sometimes tumbledown housing and taverns with leaking thatch roofs. That’s where the service folk of the city live when they aren’t laboring, the basalt city walls rising at their backs.

Yael could stop anywhere in between; the whole city is at their fingertips, the Clauneck name a key that opens every lock.

Instead, they turn south and switch the steed to Canter .

Alviss Oreborn would be happy to have the Claunecks in hisdebt, though Yael’s family can easily compensate him for the beast. But that won’t be necessary. Even as they race alongthe Queens’ Road toward the outskirts of the capital, where the estates give way to flat fields just inside the city’s black walls; even as they approach the southern gate; even as they toss a few silver denaris from the belt purse they wore at the party to the watchmen, who are bewildered to see a lone young noble galloping into the sunset and the wild-smelling countryside, but have no orders to stop them; even then, they tell themself this is just a quick ride. One last chance to feel young again.

One last chance to feel as they did when they believed that growing up would mean a great adventure, and not the end ofit.