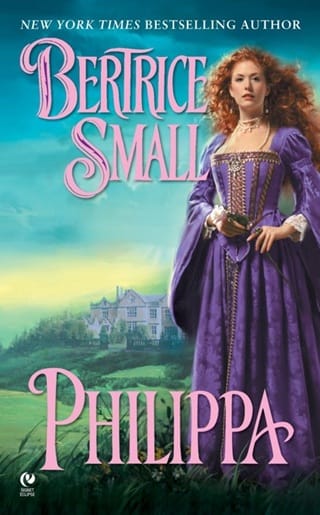

Philippa (Friarsgate Inheritance #3)

Chapter 1

“ W hy did you not tell me?” Philippa Meredith demanded of Cecily FitzHugh. “I do not think I have ever been so sad and angry in all of my life. We are best friends, Cecily. How could you keep this from me? I do not know if I can ever forgive you.”

Cecily’s blue-gray eyes overflowed with tears at Philippa’s words. “I didn’t know,” she sobbed piteously. “It is as big a surprise to me as it is to you. I only learned of my brother’s decision this afternoon as Giles was speaking to you. My father said they kept it from me because they knew I would tell you, and it wasn’t up to us to speak with you. It was Giles’s responsibility. I think my brother is horrid, Philippa! We were to be sisters, and now you will marry someone else.”

“Who?” Philippa sniffed. “I am not noble, and while I am considered an heiress, my estates are in the north. Giles’s selfishness has probably rendered me impossible to marry off. Look how long it took your parents to find you a proper bridegroom. And soon you will be married, Cecily, while I shall wither away.” She sighed dramatically. “If your brother has decided to devote his life to God, then perhaps it is a sign that I should too. My great-uncle Richard Bolton is the prior of St. Cuthbert’s, near Carlisle. He will know of a convent I may enter.”

Cecily burst out laughing. “You? A nun? Oh, no, dearest Philippa, not you. You have too great a love of all things worldly to be a nun. You would have to give up all the possessions you so love, like beautiful clothing, jewelry, and good food. You would have to be obedient. Poverty, chastity and obedience are the rules in any convent. You could never be poor, docile or biddable, Philippa.” Cecily’s blue eyes danced with merriment.

“I could too!” Philippa insisted. “My great-aunt Julia is a nun, and my father’s sisters.”

Cecily laughed all the harder.

“Well, what else is there for me now that your brother has rejected me?” Philippa demanded of her best friend.

“Your family will find you another husband,” Cecily said practically.

“I don’t want another husband!” Philippa cried. “I want Giles! I love him, and I shall never love another. Besides, who would want to exile themselves to the north where my estates are located? Even Giles said the thought of having to live at Friarsgate made him miserable. Why my mother fought so hard to retain it I will never know. I don’t want to live there either. It is much too far from the court.”

“You are only saying that because you are disappointed in my brother,” Cecily said. Then she changed the subject. “My father has written to your mother telling her of Giles’s decision. The messenger will leave for the north in the morning. Do you want to send a letter to your mother with him?”

“Aye, I do,” Philippa said. She arose from where they had been sitting together in the queen’s antechamber. “I will ask the queen’s permission to go and write it now.” Without a backward glance to her friend Philippa moved serenely across the room. At fifteen she very much resembled her mother at that age, with her slender carriage and her auburn hair, but her eyes were not Rosamund’s. Philippa had her father’s changeable hazel green eyes.

Approaching the queen, she curtseyed and waited for permission to speak. It was given almost immediately. “What is it, my child?” Queen Katherine asked, smiling.

“Your highness has undoubtedly heard of my misfortune by now,” Philippa began.

The queen nodded. “I am sorry, Philippa Meredith,” she said.

Philippa bit her lip, for she suddenly found herself near tears again. She swallowed hard, and then forced herself to continue. “Lord FitzHugh is sending a message north on the morrow. I should like the courier to also carry a letter from me to my mother. With your highness’s permission I will withdraw to write it.” She curtseyed again, giving the queen a weak smile.

“You have our permission, my child,” the queen said. “And you will give your mother our kind regards, and say that if we may be of help to her in seeking a new match for you we shall be glad to come to her aid, but I remember your mama likes to do everything on her own.” Queen Katherine smiled with fond remembrance.

“Thank you, your highness.” Philippa curtseyed once more, and backed away. She slipped from the queen’s rooms, hurrying to the maidens’ dormitory where she might be alone with her troubled thoughts as she wrote to Rosamund. But the girl Philippa liked least among the maids was there preening as she prepared to join the queen’s ladies.

“Ohh, poor Philippa!” she cried with false concern as she saw her enter the chamber. “I understand you have been jilted by the earl of Renfrew’s son. What a pity.”

Philippa’s eyes narrowed. “I do not need your concern, Millicent Langholme, and besides it is none of your business.”

“Your mother will have some difficulty finding you a decent husband now, and especially as your estates are so far north,” Millicent murmured. “Did I hear aright? Giles FitzHugh is to become a priest? I wouldn’t have thought it of him. He must have wanted to get out of marrying you quite badly to do that,” she tittered. Then she smoothed her velvet skirts, and adjusted her gabled headdress.

Philippa had never wanted to hit someone so much in all of her life, but her situation was bad enough without deliberately bringing disgrace upon her family by assaulting another of the queen’s maids. “I have no doubt that Giles’s vocation is an honest one.” She found herself defending him although what she really wanted to do was pound the wretch who had deserted her with both of her fists. Then she said, “You had best hurry, Millicent. The queen was looking for you.”

Seeing she could not bait Philippa into bad behavior, Millicent Langholme hurried off without another word. Philippa opened the chest that held her possessions, and drew out her writing box. Opening it she sat down on her bed to write, and when she had finished Philippa gave the sealed letter to a page who saw it was dispatched with the earl of Renfrew’s messenger, who rode north the following day.

Reading her daughter’s missive some days later, Rosamund gave a little shriek. “Give me Lord FitzHugh’s letter, Maybel. Quickly! Just when I thought all was well, it would appear we have difficulties again.”

“What is the matter?” Maybel handed the younger woman the packet from Lord FitzHugh. “What does the earl say?”

“A moment,” Rosamund replied, holding up a delicate hand. “God’s foot and damnation!” Her eyes quickly scanned the parchment, and then she set it aside. “Giles FitzHugh has decided to enter the priesthood. There will be no betrothal between him and Philippa. The wretch! Well, I never liked him that much anyway.”

Maybel gave a little shriek of outrage.

“The earl apologizes,” Rosamund continued, “and says he still thinks of Philippa as a daughter, and always will. He offers to aid me in finding another husband for Philippa. I must send to Otterly for Tom. Even though he has been away from the court for several years he will still be wiser than I in this matter. Poor Philippa! Her heart was so set on that boy.”

“A priest,” Maybel lamented. “That fine young man! ’Tis a pity, and now our lass left bereft at her age. That selfish lad might have told her sooner, I say.”

Rosamund laughed. “So do I,” she agreed. Then she picked up her daughter’s letter again, and began to read it completely, shaking her head as she did so. When she had finished she set it aside with the other. “Philippa says there is nothing for her but to become a nun. She asks that I consult with my uncle Richard as to a good convent.”

“Stuff and nonsense!” Maybel said. “The lass is overwrought, although who could blame her under the circumstances. However, I do not see Mistress Philippa taking holy orders at all, no matter what she says.”

Rosamund laughed again. “Neither do I, Maybel. My daughter has too great a love of all things fine to give them up. Tell Edmund to send to Otterly for Tom today. And see that the earl’s messenger is properly cared for, Maybel.”

“As if you should have to tell me such a thing,” Maybel muttered as she made her way from the hall to find her husband. Thank God Rosamund was sending for her older cousin to help in the matter. Tom Bolton would know just what to do, unlike Rosamund’s husband who would simply lose his temper.

Thomas Bolton, Lord Cambridge arrived from his estates at Otterly two days later.

“What is the emergency that I have been summoned to come with such haste?” he asked his cousin. “The children are alright, aren’t they? And where is that reckless Scots husband of yours, cousin?”

“Logan is at Claven’s Cam seeing to a strengthening of the defenses. The border has been unruly ever since Queen Margaret was driven from Scotland,” Rosamund replied. “The children are fine. It is Philippa with whom we have difficulty, Tom. I need your advice and counsel badly. Giles FitzHugh is entering the priesthood.”

“Jesu and all the beautiful angels in heaven!”Thomas Bolton swore. “And now our lass is left high and dry, having just turned fifteen, without prospects. ’Tis a caddish thing to do. Surely the lad might have given us more warning. These churchmen are so thoughtless. All that seems to concern them is God, and amassing great wealth.”

“Uncle Richard should not like to hear you saying such a thing,” Rosamund laughed. Then she grew more somber. “What am I to do, Tom? Oh, I know, another husband must be found for my daughter, but how will I go about that? We had an earl’s son for Philippa. How will we do as well again? And to make matters worse my daughter is threatening to take the veil!”

Thomas Bolton burst out laughing, and he laughed until the tears rolled down his face, staining his elegant velvet doublet. “Philippa? A nun?” He laughed some more even as he brushed away the evidence of his humor. “Philippa has too great a love for the good life and for beautiful things to allow her disappointment to drive her to a convent,” Lord Cambridge finally said. “Of all your daughters, dearest cousin, Philippa was always my best pupil. Her knowledge of gemstones astounds even me, and the finely woven woolen underskirts she wears in the winter must always each be protected by a layer of silk lest her fragile skin be chafed. The rough linen robes of a holy woman would certainly not do for our Philippa. Well, dear girl, there is nothing for it. She must come home until the ignominious fate Giles FitzHugh has left her to can be forgotten. Send a message back to court to that effect, directed to the queen. Certainly Katherine will understand, and be gracious enough to welcome Philippa back to her service at some later date. In the meantime I must think on possible matches for our lass. She is ripe for marriage now, but if we allow too much time to pass her chances will be gone.”

Rosamund nodded. “I agree. Of course when Logan learns of Philippa’s predicament he will begin suggesting all the sons of the men he knows.”

“No Scot will do for Philippa,” Tom Bolton said, shaking his head. “She is too in love with her life at the court of King Henry, and more English surely than you are, cousin.”

“I know,” Rosamund agreed, “but you will have to help me with my husband, cousin. You know how obdurate Logan can get when he sets his mind on something.”

“The trick, dear girl,” Lord Cambridge answered her, “is not to let it get that far with your bold Scot.” He chuckled. “Do not fear. I know how to handle Logan Hepburn.”

“Indeed you do,” Rosamund laughed, “and Logan would be most annoyed if he realized it, Tom.”

“Well, I shall certainly not tell him,” Tom Bolton said with a wink. “In the meantime what does the queen say, other than she will make an attempt to find another husband for Philippa? This is not something I would choose to leave in her hands, cousin.”

“I agree.” Rosamund nodded. “However, if we call Philippa home now I fear it will make her plight more difficult to solve, Tom. Unless the queen sends her home let us leave her where she is. She is no longer a child, and she must learn to handle the difficulties that life will hand her. This is not the last serious disappointment she will face, and the lady of Friarsgate must be strong to hold this land.”

Lord Cambridge sighed. “The court is a very different world from our world,” he reminded Rosamund. “I have come to realize that I should rather face the bitterest of cold winters in Cumbria than the court. I am astounded that I survived it all. Still, if you think it best we leave her there for now I will bow to your motherly instincts.”

Rosamund laughed at him. “Oh, Tom, do not tell me you have come to love Otterly after all these years. And the quiet life as well?”

“Well,” he huffed, “I am not as young as I once was, cousin.”

Rosamund laughed again. “Nonsense,” she said. “I am quite certain that Banon keeps you on your toes. She has always been a lively lass.”

“Your middle daughter is a delightful girl,” he replied. “She has brought life into the house since she came to live with me last year. I was frankly astounded when she asked to come, dear Rosamund. But as Banon has so wisely observed, if she is to be the mistress of Otterly one day she must know all about it, and its workings. A most clever lass. We shall have to find a man worthy of her one day.”

“But first we must consider Philippa’s vicissitudes,” Rosamund reminded him. “We are agreed then? She will remain at court in the queen’s service unless Katherine sends her home. And I will thank the queen for her offer, but assure her that Philippa’s family can handle the matter of finding another husband for her. One to whom the queen and the king will, of course, give their blessing.”

Thomas Bolton smiled archly. “You have not lost your touch, dear girl,” he told her. “Yes, write the queen just that. It is perfect. And tell Philippa when you write to her that I send her my love. Now, cousin, having settled your problems I find I am ravenous. What have you to feed me? And do not drag out a pot of rabbit stew. I want beef!”

Rosamund smiled fondly at him. “And you shall have it, dearest Tom,” she said, but her mind was already considering what wisdom she would impart to her daughter when she wrote to her. It was difficult to know whether to be soft or hard with her eldest daughter. Too much sympathy was every bit as bad as not enough. It would not be easy.

And Philippa Meredith, reading her mother’s missive some days later, was neither moved to tears nor comforted by her mother’s words. Indeed she flung the parchment aside in a fit of pique. “Bah! Friarsgate! Always Friarsgate!” she said, irritated.

“What does your mother say?” Cecily FitzHugh ventured nervously.

“She offers me ridiculous advice! Disappointment, she says, is very much a part of life, and I must learn to accept it. A nunnery is not the answer to my problems. Well, did I say it was, Cecily? I am hardly the type to enter a convent.”

“But just a few weeks ago you said you were going to take the veil,” Cecily replied. “You mentioned relations who were nuns. Of course we all thought it highly amusing. You are hardly the type to be a nun, dearest.”

“So!” Philippa snapped. “You and the others are laughing at me behind my back. And I thought you were my best friend!”

“I am your best friend,” Cecily cried, “but you have been so filled with histrionics, and we all knew you were not going to become a nun. It is funny to even consider it. Now, what else does your mother say?”

“That they will find me another husband. One who will appreciate me and help me to prudently manage Friarsgate. Oh, God! I don’t want Friarsgate, Cecily. I don’t ever again want to live in Cumbria! I want to remain here at court. It is the center of the very universe. I shall die if I am forced back north. I am not my mother!” She sighed dramatically. “Oh, Cecily! Do you remember the first Christmas we had at court as the queen’s maids of honor?”

“Of course I do,” Cecily responded. “They called it the Christmas of the Three Queens. Queen Katherine, Queen Margaret, and her sister, Mary, who had been queen of France until she was widowed. They hadn’t all been together in years, and it was so wonderful. Every day offered us a new excitement.”

“And Cardinal Wolsey had to give Queen Margaret two hundred pounds so she might purchase her New Year’s gifts. The poor lady had virtually nothing, having fled Scotland after the lords there overturned King James’s will and made the duke of Albany the little king’s guardian. She should never have remarried, and especially to the earl of Angus.”

“But she was in love with him,” Cecily said. “And he is very handsome.”

“She lusted after him,” Philippa said. “She was a queen dowager, Ceci, and she threw her power and authority away just so she might be swived by a younger man. The other earls, the other lords, did not want the Douglases running Scotland. That is why they chose a new regent for little King James.”

“But John Stewart is French-born,” Cecily said. “I don’t think he had ever set foot in Scotland before he was sent for to come and be the king’s regent. And he is the king’s heir, you know. I can understand why Queen Margaret was frightened.”

“Yet his reputation is one of great loyalty and integrity,” Philippa answered.

“Twelfth Night!” Cecily said, changing the subject. “Remember that first Twelfth Night? Was it not wonderful?” Cecily looked dreamy-eyed with her remembrance.

“How could anyone forget it?” Philippa responded. “The entertainment was titled ‘The Garden of Esperance,’ and there was an entire artificial garden set upon this enormous pageant cart. The ladies and gentlemen taking part danced within that garden before it was hauled off I remember how our little baby princess Mary clapped her hands in glee.”

“How sad there are no other princes and princesses,” Cecily murmured softly. “Despite our good queen’s faithfulness, her many pilgrimages to Our Lady of Walsingham, her charitable works, there is no other child of her body.”

“She is too old,” Philippa replied as low. “She has aged even in the three years we have been here. She becomes more religious by the day, and withdraws early now from the court revels. The king’s eye has begun to wander. Do you not see it?”

“But she has never shirked her royal duties,” Cecily noted. “And she and the king have always had much in common. They still hunt together, and he goes every day after the midday meal to visit her in her apartments.”

“But he comes always with courtiers,” Philippa said. “They are rarely alone now. How does a man make a son when he hardly ever visits his wife? The king complains much, but does little to change the situation.”

“Hush!” Cecily cautioned Philippa.

“Have you noticed how he has begun to look at Mistress Blount? It’s rather like a large tomcat considering the plump and pretty little finch before him.”

Cecily giggled. “Philippa, you are dreadful! Elizabeth Blount is a charming girl, and I have never known her to be mean like Millicent Langholme.”

“The king calls her Bessie when he thinks no one else is listening. I have heard him do it myself,” Philippa murmured. “Watch his face when she dances for him again some evening.”

“She’s named after the king’s mother,” Cecily said. “Her mother was a Peshall, and her father fought for the old king at Bosworth when he defeated King Richard III. She comes from Shropshire, and isn’t that almost as far north as your Cumbria?”

“You will notice that she doesn’t live in Shropshire,” Philippa said dryly. “Like me she is a creature of the court, and she has excellent connections too.”

“It doesn’t hurt that she is quite pretty either,” Cecily remarked. “But you are right. Her cousin, Lord Montjoy, is quite in the king’s favor. And the earl of Suffolk and Francis Bryan like her too. Have you heard her sing? She has quite a lovely voice.”

“I should like to be like her,” Philippa replied wistfully. “She is so popular, and everyone notices her.”

“Especially the king, as you have noted,” Cecily said. “What if he should ... well, you know. Wouldn’t she be ruined? I mean, who would wed a girl who had ... well, you know, Philippa.”

“A lady does not refuse a king,” Philippa said. “And kings take care of their mistresses. At least King James did. Do you think our good King Henry would do any less for his mistress? It would be unchivalrous, and our king is the most honorable in all of Christendom, Ceci. Remember last summer when the sweating sickness struck England, and the king moved the entire court from London to Richmond, and then Greenwich until it had subsided. How he feared for his people. He is a great king.” Then she grew glum once again. “Are people talking about me, Ceci? Because of your brother?” She sighed deeply. “What am I to do? I am not the most eligible marriage prospect with my northern estates. Let us be frank. Your brother was a big catch for me, and my estates would have given him his own lands.”

“All the girls feel awful for you,” Cecily said. “Except, of course, Millicent Langholme. Yours was really an excellent match, but now she will do nothing but brag on Sir Walter Lumley and his estates in Kent. He is negotiating with her father, you know, and she expects to be married by year’s end.”

“You will be married by then too,” Philippa said. “And then I shall have no one here to confide in, Ceci. We have been friends, it seems, all our lives, even if we really only met when we were ten. But then the best part of my life, I think now, has been here at court. I never want to leave it.”

“I am not being married until late summer,” Cecily said, “and Tony and I will be back at court in time for the Christmas revels. And you will probably have Maggie Radcliffe, Jane Hawkins, and Annie Chambers to keep you company while I am gone. And Millicent will be in Kent as lady of Sir Walter’s estates.”

Suddenly Philippa’s lips turned up in a wicked smile. “Millicent can have her Sir Walter, but only after I have finished with him,” she said. “Now that your brother has jilted me, I am as free as a bird.”

Cecily’s blue-gray eyes grew round. “Philippa! What are you planning to do? Remember, you must consider your reputation if another suitable husband is to be found for you. You are not some earl’s daughter. You are an heiress from Cumbria. Nothing else. You must not behave in a rash and foolish manner.”

“Oh, Ceci, do not fret yourself. I merely mean to have a little bit of fun. I have surely been the most chaste of the queen’s maids until now because of my loyalty to Giles. I need consider your brother no longer. The king is being attracted to Mistress Blount. This means her other admirers will retreat back into the shadows. I mean to step into the empty space created by her loss. Why shouldn’t I? I am prettier. I have inherited my Welsh father’s singing voice, which I haven’t used at all except at the mass when I must sing discreetly. And while I will admit that Elizabeth Blount is the best dancer next to the king and his sister here at court, I dance well enough to be considered graceful. My mother will indeed find me another husband sooner than later. But given where she lives he will be a country gentleman, and it is unlikely I shall ever see the court again.” Philippa sighed sadly. “So before I am shackled. and bound to wifedom I shall amuse myself, Ceci.”

“But flirting with Sir Walter Lumley?” Cecily said tartly.

“Why not?” Philippa chuckled. “I do it not just for me, but for all of those who have had to suffer Millicent Langholme’s poisonous tongue and snide remarks over the last three years. I shall be hailed as a heroine by all the other maids of honor.”

“But what if Sir Walter should decide he wants you for his wife, and not Millicent?” Cecily asked. “Surely you don’t really want him?”

“Never!” Philippa declared. “But do not distress yourself, Ceci. I shall not be the kind of girl a man like Sir Walter would marry even at his most lustful. Like Millicent, he is a fellow who takes very seriously how he is perceived by the court. I shall toy with him just enough to anger and frustrate Millicent. Perhaps I shall even let him kiss me, making certain she knows about it, of course. Then I shall abruptly move on to another gentleman, making Sir Walter look like a fool, and glad for a girl like Millicent Langholme. Actually the wench will owe me a great debt of gratitude.”

“I doubt she will see it that way,” Cecily laughed.

“Perhaps not,” Philippa agreed with an arch half-smile.

“I never suspected that you could be so wicked,” Cecily remarked.

“Neither did I,” Philippa agreed with a grin. “I rather like it.”

“You must be careful lest the queen catch you at your mischief,” Cecily said, looking about to see if anyone was near enough to hear them, but they were at the far end of the queen’s antechamber.

“She would not expect it of me. Perhaps I shall begin my flirtation this evening. The king has arranged for us to picnic by the riverside in the long twilight. There will be paper lanterns, and before it grows too dark we shall shoot arrows at some butts being set up. Sir Walter is noted for his marksmanship. I think I shall be very bad at archery, Ceci. And I shall stand near him. Being chivalrous, he will certainly want to help me.”

“But you are an excellent archer!” Cecily protested.

“Well, it is unlikely he knows that,” Philippa said. “And if he does I will pretend that it is dust in my eye, spoiling my aim.”

“If Millicent sees it she will be furious,” Cecily remarked.

“Yes,” Philippa giggled, “but she can do naught about it for the match has not been completely set yet. Nothing is signed. Believe me, if it were we should not hear the end of it. She will not be able to scold her intended husband quite yet. Poor fellow. Were he not so pompous I should almost feel sorry for him.”

“Well, he is pompous,” Cecily said. “I wonder if you shall be able to lure him at all. You are not important at all, Philippa.”

“Ah, but I was good enough for the earl of Renfrew’s son before he decided to take holy orders,” Philippa answered. “He will be curious enough to be tempted.”

Cecily shook her head. “I think Giles is well rid of you,” she teased her friend.

Philippa swatted at her with a chuckle. “Perhaps, yet he still hurt me by being so dishonest, and allowing me to believe we would wed when I turned fifteen. I think he knew at least a year ago what he really wanted. Would that he had been brave and honest enough at the time to say so. He has really placed me in a most difficult position.”

“It will be alright,” Cecily soothed Philippa. “It was not meant to be.” Then changing the subject she said, “There are some gypsies camped off the London road. Let us go tomorrow, and have our fortunes told. I know Jane and Maggie will come too.”

“What fun!” Philippa exclaimed. “Yes, let us go,” she agreed.

In late afternoon the servants began setting up the tables by the riverside. Though they would be dining alfresco, white linen was spread on each board. Poles were driven into the ground for the lanterns. A pit had been dug earlier, and even now the venison was being turned slowly on its spit. The archery butts were set up. There were small punts drawn up on the shore for those courtiers who would enjoy a small excursion on the water in the early evening. A small platform was laid on the lawn, and chairs brought. Here the king’s musicians would seat themselves so that the court might dance country dances on the grass in the long twilight. It was the next to last day of May, and they would soon be removing to Richmond for a month until it was time for the summer progress to begin. The court would not be back in London until late autumn, for the air in the city was considered noxious and conducive to disease.

In the Maidens’ Chamber Philippa and her companions refreshed themselves, and dressed for the afternoon and evening’s entertainment. Despite her modest background Philippa Meredith always had the most elegant gowns, it was acknowledged among the queen’s maids. They were never the most lavish, but they were always the pinnacle of fashion and her good taste was greatly admired, and in some cases envied.

“I don’t know how she does it,” Millicent Langholme grumbled as she watched Philippa and her tiring woman. “She cannot be rich. Her mother is a sheep farmer, I am told. I don’t know why she is here at all, for her birth is so low.”

“You are jealous, Millicent,” Anne Chambers said. “Philippa’s father was Sir Owein Meredith, a simple knight ’tis true, but one who stood in great favor with the king, and the king’s father, for his deep and abiding loyalty to the house of Tudor. He was a Welshman, and served the Tudors since his childhood.”

“But her mother is a peasant!” Millicent persisted.

Anne laughed. “Her mother was the heiress to a great estate. She is hardly a peasant. And the gossip goes that she did the queen a great kindness at her own expense many years ago. The lady of Friarsgate spent part of her youth here at court in the company of two queens, both of whom call her friend, Millicent. You would be wise to consider these facts. Philippa Meredith is most popular among our companions. I know of no one who dislikes her, or says ill of her but you. Beware lest you be sent home in disgrace. The queen does not like those who are mean of spirit.”

“I shall be leaving soon anyway,” Millicent huffed.

“Is your marriage agreement then set?” Anne inquired.

“Well, almost,” Millicent replied. “There are a few trifling matters that my father insists be settled before he will sign the betrothal contracts.” She brushed her white-blond hair slowly. “He does not say what these matters are.”

“I have heard it said,” Jane Hawkins chimed in, “that Sir Walter wants more gold in your dower than your father has offered, and your father has had to go to the goldsmiths to borrow that gold. He is obviously anxious enough to be rid of you to put himself into debt, Millicent.”

“Oh, is that it?” Anne Chambers said innocently. “I had heard something about several bastards Sir Walter fathered, and one of them on the daughter of a London merchant who will have remuneration for his daughter’s lost virtue, support for his grandchild, and Sir Walter’s name for the lad.”

“That is an evil untruth!” Millicent cried. “Sir Walter is the most honorable and virtuous of men. He would never even look upon another girl now that he is to be betrothed to me. As for any women he may have approached in his youth, they are guilty and culpable whores who are no better than they ought to be. Do not dare to repeat such slander, or I shall complain to our mistress, the queen.”

Anne and Jane moved off giggling. They were more than aware of Philippa’s plan for Sir Walter, a pompous gentleman known for a lustful nature that he attempted to conceal. They had deliberately baited Millicent Langholme, knowing that she would be closely watching Sir Walter, and that she would be able to do nothing but fume when he succumbed to Philippa’s blandishments, which they were certain he would. None of Philippa’s friends had ever considered that she might do something like this, but she was changing before their very eyes. It was, of course, the result of her hurt feelings over Giles FitzHugh. But Millicent deserved what she was about to get.

Philippa had dressed carefully this afternoon. She was more fortunate than most of the maids of honor in that she had her uncle Thomas’s London house in which she might store a larger than usual wardrobe for herself, as the queen’s maids had but minimal space for their possessions, which had to be packed up at a moment’s notice and moved to the next royal dwelling in which Katherine would take up residence. Philippa was generous enough to share this luxury with her friends, Cecily, Maggie Radcliffe, Jane Hawkins, and Anne Chambers. Her own tiring woman, Lucy, would be sent to fetch whatever was needed when it was needed.

Philippa had chosen to wear a pale peach-colored silk brocade gown. It had a low square neckline edged with a band of gold embroidery, and a bell-shaped skirt. The upper sleeves of the gown were fitted; the lower sleeve was a wide, deep cuff of peach satin, lined in the peach-colored silk brocade, and beneath which could be seen a full false undersleeve of the sheerest natural-colored silk with a ruffled cuff at the wrist. From Philippa’s waist a little silk brocade purse hung on a long gold cord. On her head Philippa wore a little French hood, of the style made popular by Mary Tudor, edged in pearls, with a small sheer veil that hung down her back. Her long auburn hair was visible beneath the veil, and was so long it actually hung below it. About her neck Philippa wore a fine gold chain with a pendant made from the diamond and emerald brooch the king’s grandmother had sent her when she had been born.

“You are not wearing a high-necked chemise,” Cecily noted, seeing no contrasting fabric beneath her friend’s gown.

“No,” Philippa said with a mischievous smile. “I am not.”

“But your breasts are quite visible,” Cecily continued nervously.

“I need bait sufficient if I am going hunting,” Philippa returned wickedly.

Cecily’s eyes widened, and then she giggled nervously. “Oh, please, remember your reputation, Philippa! I know Giles hurt your feelings, but losing your good name is no way to get back at him. I suspect no man is worth a woman’s losing her character.”

“Frankly, from my little talk with Giles I am certain he would not care what happened to me, Cecily. He never loved me at all or he would have treated me with more kindness. If the church means more to him than marriage to me, so be it. But he did not consider the difficult position into which he was thrusting me. He thought only of himself. And that I cannot forgive,” Philippa said. “I have kept myself chaste for marriage. I have never even allowed a boy to kiss me, as you well know, although others have. You have! Soon enough my mother will find some propertied squire, or my stepfather will bring forth the son of one of his Scots friends. I shall have to marry, and I shall have had no fun at all! And worse, I shall have to leave court. So what if I am a little bit naughty now. What matter if I gain a slight reputation for myself. The squire or the Scot will never know. I will retain my virginity for my husband, whoever he may be.”

“Well,” Cecily allowed, “you have really been far better than the rest of us. And now that the king’s minions are out of favor thanks to Cardinal Wolsey, I suppose it is safe to trifle with a few of the young men here at court.”

“Starting with Millicent’s Sir Walter,” Philippa replied. “I shall teach the little bitch to talk behind my back. And the best part is that while she will be angry at Sir Walter, she will still have to wed him, and she will want to for the prestige such a marriage will bring her.” Philippa chuckled.

“Poor Sir Walter,” kindhearted Cecily said. “He is marrying a shrew.”

“I do not feel sorry for him at all,” Philippa responded. “He is in the midst of a negotiation to marry, yet he will be easily tempted by just a glimpse of my breasts. I do not think him an honorable fellow at all. He and Millicent deserve each other. I expect they shall be extremely unhappy together.”

“Have you no pity then?” Cecily asked.

Philippa shook her head. “None. If a man cannot be honorable, then what is there? My father, they say, was an honorable and gentil knight. So is my relation, Lord Cambridge, and my stepfather, Logan Hepburn. I would certainly not settle for anything less in a man.”

“You have become hard,” Cecily responded.

Philippa shook her head. “Nay, I have always been exactly what I am.”