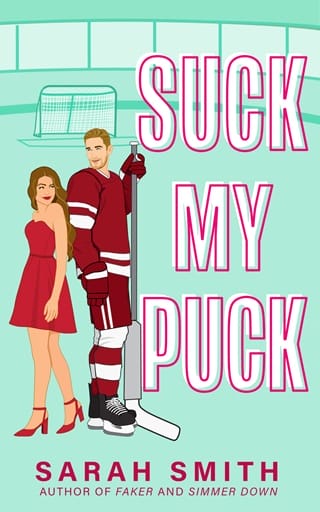

Suck My Puck (Denver Bashers Series #3)

1. Braden

Chapter 1

Braden

T he puck sails past my head, sinking into the back of the net.

That familiar dread slices through me. I mutter a curse as I reposition my glove and try to refocus.

It was just one goal. This is practice. It doesn’t count.

Except I know it does.

I look over at Coach Porter, who’s standing a dozen feet away. He’s the head coach of the Denver Bashers, the professional hockey team I play for. Next to him is Coach Sadler, the team’s goalie coach. They’re staring at me, studying me. Undoubtedly noticing how off my game I’ve been this entire practice.

This morning we’re doing stick and puck, and it’s kicking my ass. I don’t normally let in this many goals, even during practice. But my performance has been dog shit today. I was a mess even before I got here.

I huff out a breath when I think about how I overslept this morning. I was in such a rush to make it to practice on time that I forgot my phone. I left it on my bathroom counter with the music blasting. That’s always been my normal pump-up routine before practice, playing music while getting ready. But I was so out of it that by the time I realized I had forgotten my phone, I was halfway to the arena, and it was too late to turn around and get it.

My neighbors probably hate me right now.

God, I hate feeling so off. I hate playing like shit.

But I’ve been like this ever since I lost the playoffs for my team last season.

That dread inside me expands, tightening around my lungs and seeping all the way down my chest. It settles in the pit of my gut, burning like gasoline.

I think back to the moment I fucked it all up. We were tied in the series with Boston. We had three wins, and so did they. It was game seven, and we were tied, so we went into overtime. We were minutes away from making it to the final round of the Stanley Cup playoffs.

I was laser-focused. I tracked that puck as it flew across the ice, like a cat tracking a mouse. Never once did I let it out of my sight.

And when Boston’s best player took possession and headed for me, I was ready.

At least, I thought I was.

But then he faked me out. He pulled his stick back like he was going to shoot to the right side of the net, and I dove. A split-second later, the puck flew past my left shoulder into the net. And it was all over.

We lost. Because of me.

It’s been months since it happened, but I still can’t stop thinking about it, still can’t stop feeling like the biggest failure on the fucking planet.

My teammates were cool about it. Not one of them blamed me for the loss. Even the coaching staff didn’t come down on me for fucking it up.

They didn’t have to, though. Because the second I let that puck into my net, I’ve been silently blaming myself.

I was the last line of defense when everything was on the line. And I fucking blew it. I’m the one that let my team down. I’m the reason we lost out on our chance at the Cup.

My dad’s voice echoes in my mind.

You’re not good enough. Not even close.

My throat aches with that familiar pain I’ve felt almost my entire life.

Most hockey dads would be thrilled that their kid made it to the pros. Not my dad.

I think about how I was drafted in the last round of the NHL when I was eighteen. I was pick number two hundred. It wasn’t an impressive showing. I know it wasn’t. There were plenty of guys who were better than me, who were drafted earlier than I was, who earned more lucrative contracts.

But still. I had made it to the pros. Other guys around me who got drafted that same round, their families were excited and proud. I remember how they hugged and cheered as their names were announced. Not my dad. He didn’t even look at me, didn’t even stand up from his seat to shake my hand or hug me when my name was announced.

Because it wasn’t good enough for him. I was never good enough for him. I don’t think I ever will be.

That familiar pain radiates through my chest. I take a second to breathe through it.

I haven’t spoken to him in over a year. All he ever does is talk about how much I suck and what I need to do to be better. That’s the shitty part about having a hockey coach for a dad. Even when he coached me in college, he never complimented me. He always zeroed in on my weaknesses. It didn’t matter if I played my heart out or if I had two shutouts in a row. In his eyes, I always did something wrong.

I take a second to breathe through the pain. Forget him.

I force myself to refocus on the moment, on trying to salvage my performance during this practice. Xander Williams, the team’s star center, skates up to me with the puck. He takes a shot, and I catch it in my glove. Theo Thompson, our team’s top left winger, is up next. He slaps the puck to the right side of the net. I dive and manage to block it.

Del Richards, the team’s two-way center, is up next. I tense. He almost always gets a shot past me in practice.

And that’s exactly what happens when he shoots. He aims high, just over my left shoulder. I try to grab it with my glove, but I’m a half-second too late. The puck lands at the back of the net.

I mutter a curse and try not to pay attention to the way Coach Porter and Coach Sadler keep looking at me.

Practice ends, and we circle up around the coaches.

“Solid practice, gentlemen,” Porter says. “We’re always a bit rusty after the break. There are some areas we can improve on.” He glances at me. That uneasy feeling claws deeper into my chest.

“I know we can get it into gear though in time for the first game of the season,” he says. “We always do.”

He says a few more things before dismissing us, and we head for the locker room. On the way out, Coach Sadler stops me.

“Blomdahl, can we chat for a sec?” he asks.

I nod. He waits until we’re the last ones on the ice before he turns to look at me.

“How are you feeling?” he asks.

“Fine. ”

He frowns. “You look stiff when you’re in the net. It’s been like that these past few practices. And the first preseason game we played.”

The muscles in my neck and shoulders tighten as I try to gauge how honest I want to be in this moment. I don’t want to lie to my coach, but I don’t want him to know how shitty I really feel. I don’t want him to think I can’t handle being the starting goalie for the Bashers anymore.

He crosses his arms over his broad chest and sighs. His frown doesn’t budge. “I can tell you’re still holding on to what happened in the playoffs.”

I start to shake my head, but he stops me with a stern look. “Don’t lie to me. I know you. We’ve worked together for four years, ever since you were traded to this team as an eager and energetic twenty-four-year-old. You can take a while to shake things off. You always have.”

My shoulders sink with the breath I let out. I force myself to straighten back up. Goalies are supposed to have nerves of steel. We’re supposed to be gritty and tough and bounce back when we have a bad game or a bad practice.

I used to be able to do all of that.

“Look, I know I haven’t been playing my best,” I say. “But it’s the preseason. It’s like Coach Porter said, we’re all a little rusty.”

Coach Sadler studies me. “Have you tried other ways of processing what you’re feeling? Like meditation?”

I shake my head. “I never last more than a few minutes. I guess I’m bad at quieting my brain.”

“There are apps you can use. Or you could go to a class. I can recommend some really good meditation instructors.”

“Yeah, okay. Maybe.”

“You could see a sports psychologist.”

“That’s not really my thing.” I try not to sound as off-put by his suggestion as I feel. Just the thought of talking to a stranger about my insecurities and problems makes me want to crawl out of my skin.

Coach Sadler hesitates for a second. “Look, I don’t want to stress you out, but you know what will happen if you can’t get out of this rut.”

That dread from earlier resurfaces, gnawing at the pit of my stomach.

I nod. “I know.”

Rumors that I’ll be traded because of how I choked during the playoffs have been all over sports news and social media for the past few months. Thankfully, no official talks have happened, at least that’s what my agent tells me. But if I can’t get my shit together, if I can’t start playing well again, I have no doubt I’ll be dropped from the Bashers for a worse contract with a worse team.

My dad’s voice sounds at the back of my mind again.

You’re not good enough. Not even close.

Coach Sadler pats my shoulder. “I’m here to support you. So whatever you need to do to get over this slump, do it. No matter how off-the-wall it is, it’s worth trying.”

“I will.”

I head to the locker room, my anxiety spiking despite how certain my tone was when I spoke to Coach Sadler.

I need to blast through this rut. My entire career is on the line. But I have no idea how to do it.