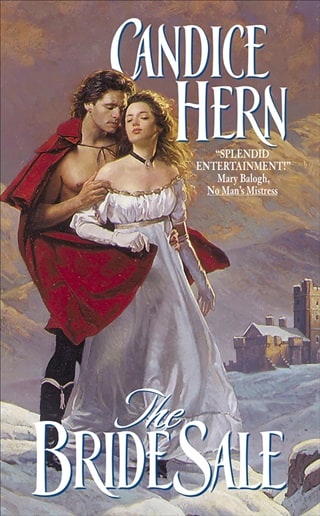

The Bride Sale

Chapter 1

7%

The Bride Sale

Chapter 1

7%

Cornwall

October 1818

“C’mon, me laddies. What’m I bid fer this fine bit o’ flesh?”

“‘Alf a crown!”

Raucous laughter almost drowned out the auctioneer’s rude response to the opening bid. James Gordon Harkness, fifth Baron Harkness, leaned against the rough granite wall of the village apothecary shop just off Gunnisloe market square. The lane and its shops were deserted; most of the villagers and market-day travelers had gathered in the square to watch the livestock auction. James nibbled on the last bit of savory meat pie as his servant loaded the carriage boot with the day’s purchases: several bolts of local wool, a few hammered copper cook pots, two large bags of seed, a brace of pheasant, a basket of smoked fish, and three cases of wine.

“Two pounds!”

James licked the pastry crumbs from his long fingers as he listened to the auction taking place around the corner. The voices of auctioneer and bidders rang clearly in the crisp air of early autumn.

“Two pounds ten.”

“Aw, c’mon,” a female voice shouted above the din. “The poor cow be worth more’n that, you bleedin’ idiot.”

“Not to my man, she ain’t,” another female replied, eliciting howls of laughter from the crowd.

“Two pounds fifteen!”

This was followed by more laughter and the earsplitting din of what had to be the banging of dozens of tin kettles. Village women often took up the old tradition of kettle banging to encourage more intense bidding. It must be some prime bit of flesh indeed, James mused as the rhythmic clanging grew louder.

A stiff breeze chased a flutter of red birch leaves down the lane, and James brushed back a lock of thick black hair blown forward by the wind. He watched the leaves skitter away, but kept his ear to the auction in the square.

“Three pounds!”

As he listened, James savored the fragrant scent of freshly baked cinnamon buns and meat pies, of roasting pig and rabbit shank, of fresh cider and ale. The delicious smells and the sounds of gaiety and fierce bartering inevitably drew his thoughts to earlier times, when he might have enjoyed such a day, when he would have been a welcome participant. Now he would not willingly walk into a crowd that size, a crowd of people who knew him, knew who and what he was.

He seldom ventured into Gunnisloe at all, though it was the closest market town. He preferred the larger, more distant markets of Truro or Falmouth, where he was not as well-known. But he had business in Gunnisloe today. Taking advantage of market day, he had sent his footman into the stalls to purchase a few household goods. While the markets bustled and thrived in the village square, James had kept his distance. He was in no mood to endure the strained silence, the wary glances, the hushed whisperings that would inevitably follow his entry into the public square.

The footman closed the boot and locked it, then opened the carriage door and stood aside. James pushed away from the granite wall and walked toward the open door. He replaced his curly brimmed beaver on his head and tugged it low against the wind.

“Four pounds!”

“Don’t ’ee dare bid on her, Danny Gower, lest ’ee want yer heart ripped clean outa yer chest.”

Peels of laughter and more banging of tin kettles followed this interesting pronouncement. James halted his ascent into the carriage. What on earth was going on? He had never before heard a crowd behave in such a strangely boisterous manner at an auction. What the devil was so special about this particular cow?

His curiosity got the better of him, and he stepped away from the carriage. Just one look was all he wanted. Just to see for himself what all the fuss was about. Just one quick look and he would be on his way.

“Five pounds!”

James walked the few steps to the end of the lane and peered around the corner, hoping no one would notice him. He quickly removed his beaver, realizing the tall, elegant hat would act as a beacon, drawing the attention of the simply dressed villagers and miners. But he needn’t have worried. When he moved to the edge of the crowd of perhaps two hundred people or more, no one paid him the least mind.

For a moment he savored the once-familiar hustle and bustle of Gunnisloe on market day. Makeshift pens lined one side of the square where cattle and sheep were exhibited for auction. Many were already being rounded up and led away by their new owners. In one corner, several dozen individuals and families sat at long trestle tables and benches that were lined up in a herringbone pattern and sheltered from the wind by a temporary awning of striped canvas stretched over wooden poles. The substantial figure of Mag Puddifoot threaded her way among the tables, ladling out portions of her famous furmity pudding, just as she had done since James was a boy. Colorful carts and stalls selling all manner of goods and produce dotted the rest of the square’s perimeter. Sweet and pungent aromas from the food vendors—stronger and more seductive here than in the adjacent lane—caused James to forget for an instant why he had made so bold as to enter the square in the first place.

“Six pounds!”

James’s gaze darted warily through the crowd as he moved closer. No one had yet noticed him. All eyes were on the stone plinth next to the market cross where the auctioneer, old Jud Moody, stood with one arm raised and stirring the air, punctuating the banging of the kettles and urging the crowd on to higher bids. In Jud’s other hand was a leather harness attached to the neck of a woman.

A woman.

What in blazes was going on here?

The men in the crowd were actually offering up bids of purchase for a woman. Not a prized bit of livestock after all, but a flesh-and-blood human being.

A wife sale.

He had read of wife sales among the lower classes who could not afford a legal divorce. He knew, too, that the courts turned a blind eye to such illegitimate proceedings, and even the subsequent remarriage of either party. Yet there appeared to be no prearranged buyer here, as was normally the case. This poor woman was being offered up for bid like a broodmare or a common packhorse.

His own disgrace almost paled when compared to such an infamous transaction. Almost. But here were the good people of Gunnisloe, steeped in their salt-of-the-earth Methodist prudery, now sunk so low.

And they dared to judge him? The self-righteous, hypocritical prigs. These same people who dashed into doorways at the very sight of him, clutching their terrified children to their breasts, unwilling to forgive his sins, obviously had no scruples about subjecting one of their own to such a sinful public display.

But as he looked more closely at the woman on the plinth, she did not appear to belong to one of the local mining or farming families. She wore a heavy blue cloak that appeared, even from a distance, to be a high-quality, well-tailored garment, along with a bonnet lined in a matching blue fabric. Both garments seemed to identify her as something other than a common laborer, or even a tenant farmer’s wife. Could the clothing have somehow been procured to bring a better price at auction? To make her appear more attractive?

“Seven pounds!” a man shouted. He was a stranger to James. He looked to be a tinker or peddler of some kind, standing next to a large draft horse laden with packs overflowing with tin utensils. James supposed that the sanctimonious locals would blame this whole iniquitous business on foreigners and itinerants, or even the recent influx of new workers for the copper mines. Surely their high-principled and upstanding neighbors and acquaintances would never become involved in such a shocking affair. Not the fine moor folk, who owed him their wages from the mines and the tenant cottage roofs over their heads, but who would not so much as doff their hats in his direction. Not these stolid Cornishmen, so full of Christian charity and human compassion.

“Seven pounds ten!” This bid came from Sam Kempthorne, one of his own tenant farmers, who leered at the woman with a distinctly lascivious glint in his eye. So much for Christian charity.

“Eight pounds!” the tinker retaliated.

“Eight pounds ten.”

The woman stood stiff and unmoving on the old stone platform. Her head was bent, the deep poke brim of the bonnet shadowing her features. Despite her outward immobility, James did not miss the slight contraction of her shoulders at each shouted bid. He was reminded of a soldier he had once watched being flogged for some minor infraction, stoically submitting to each stroke of the lash.

He looked behind her and saw a well-dressed young man standing to the side of Jud Moody. The man’s eyes were wide with what might have been fear. They scanned the crowd and then pinned Moody with a frantic look of desperation.

“C’mon, lads,” old Moody shouted to the crowd after nodding at the young man. “Her may be a stranger an’ all, even a foreigner from up-country. But tedn’t no common hedge whore, she. Her be quality, I’m tellin’ ’ee. Can’t sham breedin’ like that. Goes down to the very bone. Wife of a gen’l’mun, too. Worth more’n a piddlin’ few quid, by God. Gimme a real bid, a reas’n’ble bid.”

“Give us a better look at ’er, then!” a man’s voice shouted.

Old Moody tugged on the halter attached to the woman’s neck, causing her head to jerk up for a brief moment. “C’mon, dearie,” he said. “Show ’em wot yer offerin’.”

She looked younger than James had expected, perhaps in her mid-twenties. Darkish hair was just barely visible beneath her bonnet. Her eyes appeared to be dark as well, though James was not close enough to be certain. She again lowered her gaze, and appeared to be terrified. No, not quite terrified, he decided as he studied her further. Fear drained her face of all color, but there was also the merest hint of defiance in the tight jaw and in the square set of her shoulders when Moody pulled on the halter. And in the way she jerked her neck and pulled right back, causing Moody to bobble, unbalanced, for a moment. Good for her, James thought. Good for her.

“See wot a fair one her be,” Moody continued. “Fine-lookin’. Still got all her teeth,” he added as he chucked her chin. “Young, too. An’ built just right to warm one o’ yer beds. See here.” The auctioneer pulled away her cloak and ran his hand suggestively over the front of her dress, stretching the fabric of the bodice taut across her bosom.

James took a step forward just as Mag Puddifoot, distracted from her furmity, scowled and shook a long wooden spoon toward the auctioneer. “Here, now!” she shouted in an outraged tone. But the well-dressed young man had already slapped away Moody’s hand.

“Don’t you touch her,” the man said. The wind had whipped the open cloak over the woman’s shoulder. The husband reached over and gently pulled the cloak around her again. She shrugged away his touch.

How odd, James thought, that a man who would so callously offer up his wife as mere chattel should exhibit even that small act of consideration.

“Ah,” Moody said. “See wot a lady her is. Worth a good deal more’n a scrubby handful o’ coins, an’ this here gen’l’mun knows it. Ain’t likely to let her go fer a measly few yellow boys, is ’ee, sur?”

The husband stared at Moody for a moment, then dropped his gaze and shook his head.

“C’mon, then, lads,” Moody continued. “Who be willin’ to pay fer a real lady to wive? Who’ll tip me twen’y pounds?”

“Twen’y quid? That be a price fit fer a fine dollymop, not a wife!”

The crowd burst into laughter.

“Then buy her fer yer dollymop, Nat,” old Moody replied.

Nat Spruggins, one of James’s own tributers from Wheal Devoran, stood grinning like a fool as other men pounded him on the back with encouragement.

“Naw,” Nat replied above the laughter. “Me wife wouldn’t like it!”

“Nor an’ I wouldn’t!” replied Mrs. Spruggins, who stood nearby. “Gor, Nattie, y’ain’t got ’nuff wind at night to plow yer own field, much less ’nother man’s.”

More laughter followed.

“Best ’ee should find a bach’ler, Jud Moody,” another female voice cried out. “Ain’t no wife gonna like it no more’n Hildy Spruggins.”

“C’mon, then, all ’ee bach’lers,” Moody continued. “Who among ’ee needs a fair, young wife, then? Already broke in by this here fine gen’l’mun. Knows her way about a man’s bed, I reckon. Don’t she, sur?”

The young man glowered angrily at Moody, but then looked away and said nothing. The bastard.

“I’ll give ten quid!”

“Cheelie Craddick, don’t be insultin’. A real lady to warm the bed o’ the likes of ’ee? An’ fer a piddlin’ ten quid? Don’t make me laugh! God’s teeth, man, her be worth at least as much as yer best horse! A’right, then. Who else’ll bid? C’mon, boys. Tip me a real bid. Who’ll go twen’y quid?”

“So why he be sellin’ her, anyway?” another man’s voice rose above the hubbub. “Does her be some kinda shrew or sumthin’? Wot fer be this here feller so hell-bent on gettin’ rid of her?”

“Now, Jacob,” Moody replied. “’Ee knows how the quality be. Gets tired o’ the same woman ever’ night. Wants variety and all. An’ so, this here fine gen’l’mun is willin’ to give her up fer a fair price, and let one o’ you lucky lads have a go at her. So, who’ll it be, then?”

James frowned at the coarse words, even as the notion crossed his mind that he might enjoy having a go at her himself. But he was, of course, an even bigger bastard than this diddling husband, so it was no surprise that such a foul notion would enter his head.

He looked more closely at the tethered female. Was she truly a woman of quality? A woman of his own class? James had never heard of a wife sale among the gentry. The husband’s appearance was that of an affluent, well-tailored young man about Town. His manner was slightly skittish, even a little embarrassed.

What kind of man would do this to his own wife? How could he discard her so easily, humiliate her so publicly? What about his vows? What about his honor?

Brought up short by the absurdity of such a harsh appraisal, James chuckled mirthlessly to himself. Who was he to question a man’s honor? What right did he have to pass judgment on another man’s treatment of his wife? So what if the young man was prepared so casually to abandon her? So what if he decided to humiliate her in so public a fashion? So what if he was imbecile enough not to realize how lucky he was to have her, and how empty a man’s life could be without a wife by his side? So what? It was nothing to James. It was no concern of his.

“Wot ’bout Big Will?” a female voice shouted. “He could use a wife, an’ fer certain ain’t no one else’d have him!”

The crowd erupted in laughter once again. James followed a sudden movement toward the opposite edge of the square, where the hulking figure of Will Sykes, Gunnisloe’s smithy, stood staring at the harnessed woman on the plinth. His beefy arms—bare to the shoulder and covered with thick black hair, soot, grease, and God only knew what else—were crossed over his broad chest.

“How ’bout it, Big Will?” Moody said as several men pushed the huge man forward. “Wot else yer gonna spend yer blunt on? Here be a nice, soft female jus’ waitin’ fer yer tender touch.”

The blacksmith glared slack-jawed at the young woman, who kept her eyes averted. Big Will Sykes had lived in Gunnisloe his entire life and had always been a competent blacksmith. But his size, his general lack of intellect, and his peculiar notions of personal hygiene had made him the butt of local jokes for years. The women teased him from afar, but none would go near him.

“Wot says ’ee, Will?” old Moody cajoled. “A woman of yer own at last. A real lady, too.”

Big Will licked his lips and James felt a momentary tightening of his stomach. Did he pity the woman? Did he care? No. He did not. It was none of his concern what happened to her. It was none of his concern if the young husband happened to be a cad of the first degree, who allowed his wife to be ogled by that great slobbering animal, and who was ready to toss away his responsibilities to the highest bidder. Was James so confident of his own sense of honor? Did he honestly believe that he was himself incapable of such perfidy?

What a foolish notion, when he was in fact guilty of much more.

Urged on by the other men, Big Will edged closer to the plinth.

“She be yers fer twen’y pounds,” Moody said. “A bargain she be, too. God knows ’ee won’t never do no better.”

“That be a lotta money,” Big Will said, shaking his large head slowly side to side.

“Ah, but not fer the likes of ’ee, Will,” Moody replied. “Got plen’y of the ready stashed away, ’ee does. Make decent money at forge. And all the district knows ’ee ain’t spent a ha’penny in years. Besides, look at her, man. Look at her!”

Big Will continued to stare while the women in the crowd snickered and began beating their tin kettles once again. “Will! Will! Will!” the men shouted in time to the banging kettles. Will turned to the crowd and grinned, obviously pleased at being the center of attention.

“Will! Will! Will!”

The square throbbed with the hellish din until James could feel it through the soles of his boots.

“Will! Will! Will!”

With each shout and clang of kettles, the crowd surged forward slightly, closing in on the plinth. More revelers entered the square and James was jostled from behind. He had to scramble to keep his balance as the mob continued to push, push, push ahead in rhythm with the pounding of kettles and the pulse of a hundred chanting voices.

“Will! Will! Will!”

The big man nodded at last and turned to the auctioneer. Old Moody held up his hand for silence, and the kettle banging gradually ceased.

“Aw right,” Will said in his thick, toneless voice. He continued to leer at the woman who stood as still as Lot’s wife. She had not raised her head once during all the commotion. “Twen’y quid, then.”

Cheers and laughter rose from the crowd, and were soon drowned out by more kettle banging. James looked around him, astonished that these people, many of whom he’d known his entire life, were so eager to see this unknown, unsuspecting young woman thrust into the filthy, beefy arms of Will Sykes. They were going to let it happen; in fact, they were encouraging it to happen with no little enthusiasm.

James’s glance darted between the woman and her husband. She stood ramrod straight against the rising wind, her head still bent down. Her hands were clasped tightly in front of her, their trembling the only outward sign of her anguish. Rarely had James witnessed such courage, even on the battlefields of Spain. And the wretched husband was going to let this thing happen. The young fool made no move to stop it.

It took Jud Moody some minutes to coax the raucous crowd to quiet. “Twen’y pounds from Big Will Sykes,” he said at last. “Does I have any more bids, then?”

The silence following the auctioneer’s question sliced through James’s gut like a French bayonet. Good Lord, what was wrong with him? He did not know this woman. He did not care what happened to her. It was none of his affair. If a young woman was about to be sold—sold, for God’s sake!—to the most repulsive man in all of Cornwall, then so be it. It was nothing to James.

Still, she had not raised her head. She had no idea what fate awaited her. No idea at all. James wrenched his gaze from her and looked at the husband. The man had paled and looked as though he was about to be ill as he stared wide-eyed at Big Will. But he said nothing.

It was time to leave. James had no wish to remain for the last act of this hideous little drama.

But he could not seem to turn away.

“No more bids, then?” Moody repeated.

A knot began to form in James’s stomach. His gaze raked the grinning, laughing crowd, whipped up by the wind and the excitement of the bidding like participants in some frenzied pagan ritual.

He looked once more at the tethered woman, rigid and trembling before the impassioned mob.

Damnation.

“If I has no more bids, then, the lady be sold—”

“I’ll give one hundred pounds!”

A collective gasp rose from the crowd, followed by an ominous hush. Verity Osborne Russell looked up for the first time since mounting the plinth.

The gathering in the market square appeared incongruously small compared to the monstrous horde she had imagined. She had seen them, of course, when Gilbert had first led her into the square. But once the halter had been placed around her neck, everything had changed. The crowd had swelled and swelled into a hostile, taunting mob. To acknowledge them would have been to acknowledge what was happening, which Verity could not bring herself to do. And so she had resolutely refused to look up.

But she had felt thousands of sneering eyes raking her from head to toe, groping her with their prurient regard as surely as the auctioneer had with his wretched hands. And the rhythmic chanting had risen to such a pitch that Verity had felt herself shrinking beneath the enormous weight of that one hideous, united voice.

And the ear-shattering din of a hundred metal drums. For one irrational moment, she had believed they might take those sticks and spoons and whatever else they used to pound their kettles and turn them on her. She had actually feared for her life.

But Verity no longer interested them. All eyes had turned toward the tall, dark-haired man who stood at the back of the crowd. The man who had, apparently, just offered one hundred pounds for her.

He placed a high-crowned black hat upon his head, and it served as some sort of signal to the crowd. They parted before him like the Red Sea before the staff of Moses. He did not move forward, but seemed to glare straight at Verity. An uncontrollable shiver of apprehension danced down her spine. Her moment of terror was not yet over.

“Well, then,” the auctioneer said into the silence. No longer that of the eager, bantering pitchman, his voice had become hesitant, almost strained. “One hun’red pounds from Lord Harkness.”

LordHarkness? He was a titled gentleman? A nobleman? A small bubble of hope rose up in Verity’s chest. Perhaps he had come to put a stop to this unspeakable exhibition. Perhaps he was a true gentleman who was not about to allow this nightmare to continue. Perhaps he meant to bring Gilbert to his senses.

But no. His unwavering gaze was fixed on her. Not on the rowdy crowd that had tormented her. Not on the loathsome auctioneer. Not on Gilbert. His interest was all on Verity. This nobleman was not her savior. He had bid on her. He meant to purchase her.

“Don’t suppose any o’ the rest of ’ee can outbid His Lordship, eh?” the auctioneer said. After only the briefest of pauses, he continued. “The lady be sold, then, to Lord Harkness fer the gen’rous sum o’ one hun’red pounds.”

Sold.

A renewed and heart-pounding panic engulfed her. She had been sold. Sold.

The word reverberated in her head, louder than the crash of ten thousand metal drums, overpowering everything that had gone before. Sold.

It was impossible. This was the nineteenth century, for God’s sake. Such things simply did not happen in these modern times, in this modern, enlightened Britain. Did they?

And yet she had just been sold. Like a horse at Tattersall’s. Like a bonnet in a milliner’s window or a sweetmeat from a confectioner. Like a slave.

Verity heard Gilbert’s sigh of relief behind her. She had been sold and her husband was relieved. Was it because he was rid of her at last? Because he could now turn her over to a nobleman instead of the local blacksmith? Because he would receive one hundred pounds for her rather than a mere twenty?

It did not matter. Nothing about Gilbert mattered anymore.

Verity concentrated on the dark stranger now advancing through the crowd. The hat shadowed his face, so she was unable to get a good look at him. But something in the way he moved was arresting—an almost threatening kind of animal grace, an imperious arrogance. The unnerving silence of the crowd gave way to hushed whisperings as he walked toward the plinth. Those he passed watched him with eyes wide and mouths agape, stepping back as though afraid to get too close. Neighbor nudged neighbor and whispered in each other’s ears. Children clung to their parents. Some pointed and giggled nervously.

The man ignored their reactions and strode ahead with a haughty arrogance that implied they had every right to be afraid.

Verity watched his maddeningly slow approach and every muscle in her already tense body tightened until she began to quiver like a bow string. She made a tiny, instinctive movement toward Gilbert—but her husband was no longer available to her. He never had been, really. Whatever tenuous ties bound them had been loosened the moment he put the halter around her neck, then severed completely with the single word “sold.”

Verity clenched her hands tighter, locked her elbows and knees in an attempt to control her body. But the tighter she held herself, the more she trembled. She could not stop shaking.

The man continued his slow progress through the square. She overheard several muffled exclamations of “Lord Heartless!” But surely the auctioneer had called him Harkness. It was only her own anxiety that twisted the name into something more sinister.

But, dear Lord, how the people seemed to fear him. Who was he? And was she truly to be turned over to him like some prime bit of horseflesh, to this strange man who seemed to strike terror in the hearts of those who knew him?

Sold.

She could not stop the trembling. It overtook her completely: down into her belly until she felt queasy, and up into her throat so that she could not seem to swallow. She tried to stop it, to hold herself still, but it only seemed to get worse. Every muscle was held so taut she began to feel the sticky dampness of perspiration from the effort. Her petticoat clung to her legs and a trickle of moisture inched down the back of her neck. The wind against her damp skin chilled her. And still she trembled. Her whole body shook uncontrollably. She could not seem to stop it.

She must get hold of herself. She must not show her fear to this man, for perhaps he was one of those men who thrived on it. With slow, jerky movements, she reached up and grabbed the edges of her cloak and pulled it close about her, twisting her hands into the fabric to disguise their shaking.

When he reached the plinth, Verity saw the man’s face clearly for the first time. It was harsh and angular and frowning. Heavy black brows beetled over intense blue eyes that skewered her to the spot, rapier sharp. When at last he jerked his glance away toward Gilbert, Verity let out a ragged breath. Her heart thundered in her ears. Surely he would hear it and know her fear.

“Are you the husband?” he asked in a deep, cultured voice.

She heard a shuffling movement behind her. “Yes.”

“You wish to be rid of your wife?”

“Yes.”

A wave of white-hot anger swept through Verity at that moment, almost smothering her fear. If she could have managed it, Verity would like to have swung around and slapped her husband full across the face. How dare he wish to be rid of her? It was not as though she had ever wanted him. Their marriage had been arranged by their fathers before they had even laid eyes on each other. If truth be told, during these last two interminable years she had often wished to be rid of Gilbert. But she had not been allowed to do so, simply because she wished it.

“You will sell her to me for one hundred pounds?” the dark man asked.

Gilbert moved forward so that he was standing beside Verity. Without moving, she slanted her eyes toward him. He removed his hat and ran his fingers through his fair hair.

“Well, as to that…” He paused, smoothed his hair, and replaced the hat upon his head, adjusting it to a cocky angle. He darted a glance toward Verity. “A hundred pounds will get you the woman,” he said. “Another hundred will get you her things.”

Verity heard a sharp intake of breath from the dark man. “Another hundred pounds?” he said in a voice edged with steel.

“It…it’s a bargain, you see,” Gilbert said. “I have her trunk of clothes and personal things in my coach. For a hundred pounds she can take them with her. ’Tis a fair price. It would cost you more than that to outfit her, would it not?”

The dark stranger fixed Gilbert with a look of such fury she thought he must be scorched by its intensity. She shuddered and tightened her grip on the cloak.

After what seemed minutes, the man reached into his coat and brought out a velvet sovereign purse. He fingered it briefly, then flung it roughly at Gilbert. “Take the whole bloody thing,” he said. “There’s over two hundred pounds in it. Take it and be off. Leave her trunk behind.”

Gilbert pocketed the purse and stepped closer to Verity, who had not yet been able to move a muscle. “All right,” he said. “I’ll go. Verity, I—”

“Hold on, there, gen’l’mun,” the auctioneer interrupted. “Can’t just take the money an’ be off like that. There be papers ’ee both got to sign first.”

“Ah. Yes. Right,” Gilbert said, still looking at Verity. “I had almost forgot.”

“Follow me, then,” the auctioneer said.

He and Gilbert turned toward the rear of the plinth. Verity was obviously meant to go with them, but she could not move. The trembling had subsided somewhat, but she could not move. She stood stiff as a statue, her feet screwed to the spot. If she could take but one step, then she might be able to take another, and then another, until she was running away. Away from this nightmare.

But she could not move.

“Wait!” The dark stranger strode up the two steps and stood directly in front of Verity. He reached out for her, and Verity’s heart lurched in her chest. But then his hands circled the leather halter around her neck and began to unfasten it. “There is no need for this,” he said. He slid the halter from her neck and tossed it into the crowd below.

Verity closed her eyes and let out a long, shuddery breath, then flexed her neck. After one more deep breath she eased the tight hold on the muscles in her shoulders, her back, her arms, her legs. Inch by inch, the tension in her body was gradually released until she stood composed and still. The trembling had stopped. She slowly untangled her fingers from the folds of the cloak and stretched them wide, then reached up to touch her throat where the halter had been. Panic no longer paralyzed her. She could move now. She could walk. She could walk away.

But she did not. The dark man looked at her with an unreadable expression. Inexplicably, she wanted to smile at him, but he stepped behind her to join Gilbert and the auctioneer. Verity pressed her fingers to her lips and wondered what had got into her. She turned and walked toward the men as they leaned over a small table at the rear of the plinth. She stepped closer and saw that they examined a parchment sheet. A deed of sale, no doubt. The disposition of her future.

Gilbert wrote a few lines on the parchment and handed the quill to the dark man. He dipped it in the tiny inkwell and scrawled something quickly. Verity leaned in closer for a better look—a glimpse into her fate.

I, Gilbert Russell, doth agree to part with my wife, Verity Russell, née Osborne, to James Gordon, Lord Harkness, for the sum of two hundred pounds, in consideration of relinquishing to him all rights, obligations, property claims, services, and demands whatsoever.

And so she was to be transferred from one man to the next like a plot of land.

Verity did not for one minute believe that such a document legitimized the transaction. It could not possibly be legal. Could it? She watched as the auctioneer prepared a second copy of the document. Gilbert and Lord Harkness signed this one as well. The auctioneer sprinkled both documents with sand and handed one to each gentleman. Gilbert folded his copy and tucked it into his jacket. Lord Harkness stared at his copy, frowning, as if the words were incomprehensible to him.

He looked up and caught Verity’s eye. For the briefest instant, their gazes locked. An unexpected hint of emotion—was it pity?—flickered across his eyes, but was gone in a blink. She might have imagined it, for he was scowling again before he turned away to speak with Gilbert.

After a few terse words Lord Harkness looked toward Verity again, but did not meet her eyes. “Let us be on our way,” he said. “I believe we are quite through here.”

Indeed, she was quite through. The life she had known, all that was familiar and routine, was over.

Lord Harkness stepped down from the plinth. He did not touch her, did not take her arm, but made it clear that he expected her to follow. Verity took a deep breath and moved to do so.

“Verity, wait.”

She stopped at the sound of Gilbert’s voice but did not turn around. She would not look at him. She never wanted to look at him again.

“I…I’m sorry, Verity,” he said behind her in an uncertain voice. “It was the only way.”

She did not understand how it could be so, but did not care. She was as anxious to be rid of him as he apparently was to be rid of her. She wanted to be gone. She wanted this to be over.

“Well,” he continued, “at least now you are free of me.”

Verity said nothing, and walked away from her husband for the last time.

She took two hesitant steps toward the edge of the plinth, and stopped. Lord Harkness waited below. After a moment, he reached up a hand to her, silently offering to help her down the steps.

Verity looked at that gloved hand and knew that if she took it, she would be tacitly accepting his protection. She had no idea what role he had in mind for her—mistress, servant, prisoner, slave? He may have a deed of sale, but she would never belong to him. He may own her body, but he would never have her soul. Never.

She clasped her hands at her waist and thrust out her chin. Slowly and cautiously, for her muscles had begun to seize up again with tension, she descended the steps on her own, ignoring his proffered hand. Lord Harkness quirked a brow, and his mouth twisted into what looked like a smirk. But he had turned around and walked on before she could be sure.

He did not turn back to see that she followed. He apparently had no doubt that she would do so. He had removed her halter and turned his back on her, making certain that she knew she was free to stay behind, and knowing that she would not. How could he be so sure of her? How could he know that she would not run away?

Verity’s eyes darted about the crowded square, and she knew there was nowhere else to go. Not among these people, who had mocked her, tormented her, insulted her. At least Lord Harkness had done none of those things.

She would go with him. For now.

The whispering began as the crowd parted for them, as they had done for him earlier.

“…Lord Heartless…”

“Ea! Poor thing.”

“Wot’ll become of her?”

“How long will she…”

“Lord Heartless…”

“…her, too?”

“Do you suppose he will…”

“The poor creature, her…”

“…another victim?”

“God help her.”

Shaken by the half-heard whispers and concerned frowns, Verity clasped her hands together so tightly her fingernails dug painfully into her palms. Dear Lord, what was she headed for? What did these people believe he was going to do with her? Determined not to let the crowd see her fear, she kept her head high and followed the tall figure striding ahead. Yet for all her outward composure, she might as well have been riding through the square in a tumbril headed for the scaffold. She did not care to consider how close to the truth such an end might be.

Horrible, disjointed images invaded her mind, whispered childhood memories as incomprehensible now as then, but frightening in their implications. Hushed secrets from the last century about the Hellfire Club, about the Marquis de Sade, about white slavery.

Was this to be her fate? To be sacrificed to the whims of this dark stranger, to suffer unspeakable acts at his hand? To be tortured or even killed?

For some unaccountable reason—pride? stubbornness?—she did not want to die. Though she had nothing in particular to live for, she wanted to live.

With a determined tilt of her chin, she followed Lord Harkness to a plain, unmarked black carriage waiting in a nearby lane, blessedly removed from the market crowd. A coachman in white leather breeches, striped waistcoat, and dark jacket held the horses’ heads while a footman opened the carriage door.

Once again, Lord Harkness offered his hand to assist her into the carriage, but she ignored him and he stepped aside to speak with the coachman. When the footman, a strapping ginger-haired fellow with an open, friendly face, offered to hand her up, she did not hesitate to accept.

Inside, the coach was elegant but not opulent. The seats and walls were upholstered in tufted blue velvet, the trimmings plain brass and mahogany. Its comfort was a blessing after the poor equipage Gilbert had hired for the journey to Cornwall.

But she must not allow a friendly footman and comfortable coach to confuse the situation.

The carriage began to bounce slightly. They must be loading the boot. Verity prayed that her trunk was intact, for it held practically everything she owned. She understood now why Gilbert had told her to pack so thoroughly: He had known she would not be coming back.

The carriage door opened and the young footman stuck his head in. “Pardon me, ma’am,” he said. “But we had to unload these here cases o’ wine to make room for yer trunk. Nuthin’ fer it but to stack ’em here.” He proceeded to pile three wooden crates on the seat opposite.

Dear God, was Lord Harkness a drunkard, too? Her father had seldom taken more than a glass at mealtime. Three cases of wine would have lasted him a year. How quickly would Lord Harkness drink his way through it? And was she to play some role in his drunken debaucheries?

The subject of her thoughts launched himself into the coach, seated himself next to her, and pulled the door behind him. His thigh brushed against hers, and Verity flinched as though singed. She scooted across the bench as far as she could and pressed up against the side panel. She fixed her gaze out the window, studying the plain granite wall that faced her.

“Are you…quite comfortable?” Lord Harkness asked.

Verity nodded without turning to look at him.

“Pendurgan is less than five miles away,” he continued in an awkward-sounding tone. “We should be there in three-quarters of an hour or so.”

Pendurgan. Even the name was frightening. She was going to a place called Pendurgan with a man called Heartless. Heaven help her.

The carriage lurched and pulled away. Verity grabbed the strap and hung on for her life.