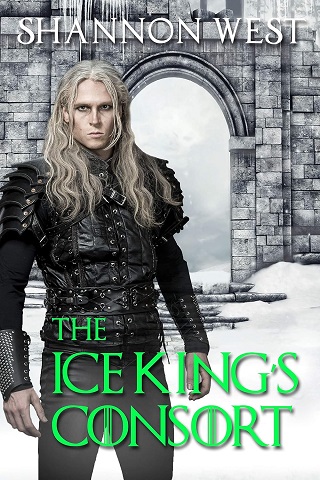

The Ice King’s Consort (The Ice King Chronicles #1)

Prologue

My history with the Quendi Elves had all the elements of a fairy tale—a love potion, a brave king, a bold and handsome hero, and even a touch of magic.

All it needed was a happy ending.

But I don’t want to get ahead of myself.

I need to go back to the beginning so I can try to make sense of it all.

It all started one bleak, cold day in December.

It was not yet as cold as it would be in January and February, when the icy winds off the Bering Sea would sweep in heavy, snow-laden clouds that turned the skies into a dark gray canopy over our heads.

Still, the fresh snow lay deep on the ground and piled up in drifts against the trees.

It had been a hard winter already, with no signs of the cold weather letting up, because winter came early and stayed long this far north.

Scattered along the edge of the vast, frozen pine forest that signaled the beginning of Elven land were massive poles of ice that we called the Quendi Ice Poles.

The Quendi Elves owned all the land between the frozen forest and the Bering Sea, a distance of perhaps three hundred and sixty kilometers, and these Poles stood like silent sentinels, glittering and shining in the pale, morning light.

They were a warning to go no farther, for if you ignored this boundary, your life was surely forfeit.

Our tiny village had been in the shadows of the Poles for as long as anyone could remember.

The sound of laughing from the village boys who sometimes came to play by the edge of the forest distracted me as I stacked the wood early that December morning, and I stopped for a moment to catch my breath and watch them.

They were daring each other to run up and touch the nearest pole or throw a rock at it to see what would happen.

They carefully stayed a few yards away, darting close and then jumping back again, shouting with laughter and ready to flee if a Quendi might suddenly take offense and come charging out of the woods.

It had never happened, to my knowledge. Their high-pitched voices drifted over to me where I stood leaning on my axe.

My father came out the back door to see what was taking me so long to cut wood.

I had been up late the night before with my little brother, Sergey, who had been ill with a hot fever and a wracking cough.

Using my grandmother’s book of recipes, I had prepared a healing potion for Sergey in the afternoon when I noticed how listless and flushed he was.

I had spent most of the night beside him, singing to him when his sleep was restless, and then toward morning, a pink rash had broken out along his thin ribs, with more of it sprinkled across his chest and stomach.

By morning, his fever had finally broken, and I had sent up a quick and fervent prayer to God, thanking him that it wasn’t more serious.

I’d had the same rash myself when I was younger, so I recognized it. Still, sometimes a more serious disease could disguise itself and lay in wait to suddenly worsen and kill you if you weren’t vigilant and watchful.

So all things considered, I had slept later than usual, and though I’d banked the fire, it was almost out by the time I got up.

It left the old, drafty house dangerously cold.

There was barely enough firewood to get a flame started, and I knew I needed to cut more, or we’d all freeze to death.

That meant I hadn’t yet made my father’s breakfast.

He was angry and querulous now as he stood beside me in the deep snow that came up over his boots, his face pale with the headache that came after drinking too much the night before.

“Hurry up, Pavel.

I’m starving,”

he whined at me.

“And it’s cold.”

I held onto my temper, took a deep breath, and managed to give him an answer without shouting at him.

“I’m trying, Father.

Go in and sit down and I’ll be in soon.”

God forbid he should actually give me a hand.

He grumbled under his breath at me but started back inside, pausing near the worn, wooden step.

Pointing down at the snow, he turned to me, looking shocked.

“Quendi tracks in the snow,”

he whispered, his voice hoarse and his whole body going stiff with fear.

“They lead up to the house. Look!”

I had already noticed them when I first came out.

One or more men wearing boots with the long, curled-up, pointed toes—a fashion the Elves seemed to prefer.

Their footprints had made only light indentations in the snow, despite the fact that the Quendi were a tall, muscular tribe.

One set of prints led up to my little brother’s window. A Quendi ice soldier must have stood there in the dark, silently looking in. Had one of the soldiers watched me while I sang to Sergey in the candlelight? To what purpose? A shiver traveled down my spine at the idea.

“There are more tracks behind the house,”

I said softly, trying not to alarm my father any more than I had to, but it didn’t work.

“What does it mean, Pavel?”

he cried, looking behind him into the dim, twilit woods.

The shadows beneath the trees seemed to thicken and grow darker the longer we watched.

"Shh, Father, calm yourself.

It may have only been curiosity.

Don't attract attention.

They could be watching."

The prints of the long, pointed-toe boots trailed all along the back side of the house and over to the hen house.

One of the cloven-footed stags the soldiers traveled on had stood by the coop, leaving faint hoof prints in the snow where the beast had impatiently stamped its feet.

The marks in the snow weren’t deep enough to be someone else snooping around or trying to play a trick on us.

None of the hens were missing, either, but when I’d gone in to check them, they’d all been huddled together in a panicked, feathery heap.

“But what are the Quendi doing here?”

my father said, his eyes wide and frightened, glancing back over his shoulder at the forest.

“We have nothing of value—nothing they’d want.”

“Who knows what the Quendi might want?”

I glanced over at him and saw him shivering.

“Go back inside, and I’ll come build up the fire.

You and Sergey eat some bread and drink tea until I can make the porridge.”

He nodded but still hesitated, his wide-eyed, terrified gaze fixed on the forest behind me.

The sun suddenly slipped behind one of the snow clouds that had been gathering all morning and a frigid breeze blew across my neck and slipped an icy finger down the back of my shirt.

Nervously, I peered deeper into the shadows, thinking I may have seen something moving in the darkness under the snow-tipped evergreens.

Beside the trees, the Poles stood, majestic and massive.

It was said that the Poles once stood at the top of the world.

Legend said the Ice Giants came to steal the Ice Poles because of their magical properties and take them to the tsar in St.

Petersburg.

But the Poles belonged to the Quendi, and the Elven Ice King had come with his army, and they prevailed in a battle against the Giants. In the end, the soldiers couldn’t move the massive Poles all the way back to the North, so the Elven king found a wizard to stand them up, all along the perimeter of their land, as a warning and a beacon to any trespassers who might be foolish enough to try to steal from the Elves again.

There was no account of what happened to the wizard.

The house where we lived was on the outskirts of Latva, the tiny village closest to Quendi land.

And our house was closer still, on the edge of the ice forest, where few dared to live.

We weren’t brave—we simply had no choice.

The house had been standing empty when my father gambled away our old home and had to go looking for another. This house, in the next village over from ours, had been the only one my father had been able to get, because the owners had been frightened away—no one seemed to know by what—but even more importantly to my father, the house had been dirt cheap.

The Quendi didn’t usually come near the families in our village.

We were all far too poor for them to bother with, and we all knew better than to anger them by even thinking of hunting the white game on their land.

It was said that years ago, some young brothers who belonged to a desperately poor family had crossed over into the Quendi forest to poach a few of the white rabbits that lived there.

Their bodies were found the next day, just outside the boundary lines marked by the Poles, bloodied and torn to bits. Some said a bear had killed them. While it was true that from time to time the white bears came as far south as the Novaya Zemlya islands in northern Russia and even down into a few of the villages on the mainland, most of us knew it hadn’t been bears that had killed the young hunters.

They had run afoul of the Quendi and paid the price.

Other tales of their savagery were more inexplicable.

In a nearby village, they told of a Quendi ice soldier who had been found by hunters with terrible, bloody wounds, on the edge of the forest, next to his huge reindeer who stamped his feet and snorted at the hunters to keep them away.

They had managed to get a coil of rope over the stag’s neck and tied him to a nearby tree.

They had bound the soldier’s wounds and given him food and ale to revive him. Yet as soon as he regained his strength, he took up his sword and slaughtered all of them. Only one man had survived long enough to stumble back into the village and tell the others what had happened.

There were also tales of the Quendi kidnapping beautiful young women and men from time to time and taking them back to their Ice Kingdom to become wives and husbands.

But that had been in the time of our great-grandparents, and no one had gone missing like that for many years.

Only one woman had ever returned to my knowledge.

She had suddenly shown up at the front door of her old family home one morning before dawn, wrapped in thick, rich furs, and still lovely and youthful, though she’d been missing for over twenty years.

Her family had all grown old since she’d been taken, while she hadn't aged a day.

She told them the old Quendi king had died, and taking mortals was not anything the new king had any interest in.

“Mortals are too fragile,”

the new Ice King had decreed, "and far too much trouble." The woman’s husband, one of the Quendi ice soldiers, had been killed in battle, so the new king had sent her back home.

Her family had found her odd after so many years among the Elves, and though they tried to be kind to her, she had pined for her dead husband and her old home with the Quendi, eventually passing away one night in her sleep not too long after her return.

I’d heard these and other stories about the Elven tribe all my life.

Stories of their fierce beauty and their frigid cruelty.

The fairies, who were also capricious, might still do you a good turn if you did them one first, but not the Elves.

They were much colder and more unfeeling if you were unlucky enough to ever run across one. My grandmother used to say that Elves were dangerous and powerful beings who were never to be trusted. They could at times be friendly to humans but could also be callous and heartless. Never, ever put your trust in one, she said.

Too bad I hadn’t listened to more of her stories.

I shivered as I gathered up an armful of wood and hurried inside.

My brother was sitting at the table beside my father, and I was glad to see my father had at least shifted himself enough to give him a mug of last night’s cold tea and a piece of bread.

Sergey stared at me with rosy cheeks, but eyes that were at least clearer.

I touched his head and found it cool, so I stirred up the fire to get breakfast started. I made a tisane from barley and some healing herbs—some I grew myself and some I gathered in the fields—using one of my grandmother's old recipes, and I made Sergey drink it down. Meanwhile, my father grumbled and complained, as I boiled two more pans of water—one for the morning tea and the other for the porridge.

I played my panpipes for Sergey while we waited.

My grandmother had first given me the instrument when I was really small and had painstakingly taught me how to use it.

It was very old, consisting of six tubes, made from the canes that grew by the river.

They were fastened together with flax and candle wax and carried inside them a sweet, haunting melody that you could coax out only if you were patient, my grandmother told me. I used to practice for hours while I tended her small flock of sheep that she let graze on the hills above her house.

After breakfast, I washed up the dishes and set the pot to soaking.

Sergey said his throat was better and not as sore after drinking his tisane, and he hugged me around the waist as I stood there with my hands in the water I'd heated over the fire.

I had tried desperately to get my mother to let me do a healing for her before she died, but she'd clutched the tiny silver cross around her neck and shook her head, her eyes wide and dark.

I might not have been able to cure her. She may have been too far gone. But I might have eased her pain and helped her breathing had she not been so superstitious and afraid of the “dark magic”

as she called the healing my grandmother practiced and had passed on to me.

It had been heartbreaking to see her struggle for each breath.

I had nursed her the best I could, but with not enough money for a doctor, she had passed away despite my efforts to heal her.

She was already ill by the time we moved here, with the morbid sore throat that would soon take her life.

Traveling in the old, open wagon my father hired to move our furniture and clothing, bouncing along the rutted road between our old village and Latka so soon after her symptoms first appeared, served to make her fever worsen.

Only a few days later, the gray caul so typical of the disease covered her throat and her nose completely and smothered the life from her, despite everything I tried to do. I had fashioned a small cross to go on her grave out of pieces of pine wood. It was covered by the snow now, but I would go on Sunday if the snow stopped to try and clear some of it off her grave. She'd always suffered so much from the cold.

My grandmother had been a wisewoman in our old village before she passed, the village where we used to live—before my father gambled away our home.

My grandmother had taught me how to make healing potions and play the haunting, old tunes on the panpipes, and she left me all her books.

But my mother had called her "witch" and said her magic was dark.

It simply wasn’t true. My grandmother only ever helped people her entire life.

Her small book of “recipes,”

as she called them, were for potions that healed the sick, helped people who were down on their luck, and eased the way of true lovers.

Sometimes she had advice to the farmers for killing the blight or bringing the rain for their crops or for easing the pain of any living creature, but how could that be a bad thing? She never caused ill for anyone, but my mother refused to let me visit her, until I got old enough to stop asking for permission and would go to see her on my own.

It caused no end of trouble between me and my mother, but I couldn’t regret it.

I loved my grandmother.

She was my mother's mother, yet they'd had a falling out not long after I was born, and my mother never forgave her for whatever it was they'd argued about.

I thought part of it must have been about my father, whom my grandmother called a wastrel.

She'd predicted my mother would live to regret the day she married him, and I think, in those last days, she did.

Later, as my own healing skills began to develop, I had to wonder if my mother hadn't somehow blamed my grandmother, though she shouldn’t have.

Other than teaching me how to make the infusions from plants and herbs and showing me how to coax out the melodies from the pipes, she'd never taught me any of the other things I had learned to do.

I found out about them all on my own.

Well, mostly.

I'd walked in on the last argument the two of them had before they stopped speaking altogether, and my mother had looked absolutely terrified about something.

She had been telling my grandmother to stop "filling his head with dangerous things." I knew they'd been talking about me, yet they both looked guilty and stopped their arguing when I walked in and refused to answer me when I questioned them.

I did know that my mother had been deathly afraid ever since a wise woman in Kabrelnick, a large market town some seventy kilometers from us, had been hanged in the town square for witchcraft.

It had been unlawful, of course, and the killing had been carried out by an angry mob, but it was frightening, nonetheless.

No one in mother’s tiny village had ever indicated in any way that they thought my grandmother was anything but a good midwife and a wisewoman, though.

When she died, the whole village came to her lying-in and lit candles for her. Everyone, that is, except my mother and father. They only came when the man they'd sold her belongings to wrote to them they could come and pick up the money.

“There was talk yesterday at the tavern about the tracks seen all over the village,”

my father said, breaking in on my thoughts, as he sat at the table, nursing his tea and worrying over the tracks we'd found outside our house.

“They must be after something.

What could it be?”

I shook my head, knowing he really didn’t expect an answer.

Outside, the snow was falling down in white flakes so thick and fat I could barely see our closest neighbor out the windows.

I was supposed to go to work that day, but the storm sweeping in would prevent that.

After my father lost our house and we'd had to move from our old village to Latva, I'd had to leave school to find a job as a blacksmith's helper to buy food for our family.

It was a dirty, backbreaking job, but at the time we needed the extra coins I could earn.

Instead of going to my job that day, I worked on keeping the fire going and sweeping the heavy snow off the roof of the hen house, so the tin wouldn’t collapse in on itself.

All that long day, the snow never slackened.

In the late afternoon, I started some potatoes baking in the coals for our supper.

The clouds were so heavy, it was like nighttime outside, and the candlelight didn’t seem to be able to penetrate the dark corners of the room.

Late in the afternoon or early evening, my father started drinking krupnik out of a jug he had hidden under his bed.

He even toasted me with it when I glanced over at him and gave me a slow wink and a drunken leer.

Tonight, I would have to be on my guard and sleep in the room with my little brother.

He’d only started drinking so much when my mother died, but since then he had worked it like it was his job.

I kept a close eye on my father, who sat on his bed that evening, drinking from his jug.

I hated it when he was like this because that was the most dangerous time of all, when he was drunk and alone with just his thoughts and his grief, and no one would see him when he tried to use me to lessen his pain.

I would take no more attempts from him though.

I greatly resembled my mother, with a slight build and the same blue-black hair and eyes, but I had warned him the last time that if he put his hands on me again, I would find a way to make him stop, and I meant it.

He would have to sleep sometime, and I was through taking his abuse.

A few hours after a supper my father didn’t eat, but instead only drank from his jug and watched me from across the room with gleaming eyes, I lay down on a pallet beside Sergey’s bed, in case either of them came looking for me in the night.

The last time, my father had stopped when I shouted at him and pushed him off my bed, but I wasn’t taking any chances.

At least, I’d be harder to find if he came looking for me in the dark tonight, and I might hear him stumbling around looking for me.

I had brought in extra wood to stoke the fire since the snow was so unrelenting.

I’d never known it to snow so hard for so many days in a row.

I lay there shivering as the house settled around us, the old timbers popping and cracking, and listened to the wind rattling the windows, looking for a way to get inside.

I’m not sure what it was that woke me.

I knew I’d been asleep for a few hours, and the wind was still moaning and howling, making so much noise that even the moon had hidden itself behind the clouds.

In the freezing, pitch black darkness, I got up and felt my way to the fire, which had burned down to glowing embers.

I threw on more logs, which shifted and startled my father awake. He saw me crouched by the fireplace in the dark and lurched up, saying, “Pavel. Come here.”

I scrambled to my feet with my back to the fireplace and my fists clenched beside me and firmly shook my head.

“No.

Leave me alone.”

He stood up, a tall, hulking figure in the dark as he took a step toward me.

My breath rose in a faint cloud in front of my face as I reached for a stick of wood.

A loud, imperious crack landed suddenly on the door.

The noise was so loud it reverberated through the house, and my father cried out in alarm.

“What? Who is it? Who comes knocking on my door in the middle of the night?”

One more loud crack against the wood was his only answer.

He rushed over to the wood pile beside me and picked up his own stick of firewood, then stumbled across the room to fling open the door.

There on the doorstep stood a Quendi warrior, his eyes like silver daggers.

He was tall and lean, but no one who saw him would make the mistake of thinking him weak.

Power fairly rippled off him. He had no beard, though he was fully grown, and he wore his hair long, in a pale sweep across his shoulders. He was inhumanly beautiful, in the way an ice sculpture is, and he looked every bit as unmoving and cold. A huge stag, standing as tall as a small horse but with a much heavier body, waited impatiently behind him, stamping and snorting its frosty breath in the cold night air. It had twelve pronged antlers, bedecked with holly and hung with dark green jewels that twinkled even though there was no moonlight. On its back was a fine, white saddle.

The Quendi looked at my father with his head cocked to the side as if trying to decide what to make of him and his stick of wood.

He pulled out a purse of dark leather—dark like the rest of his clothing—and he held it up in the air in front of him.

“What-what do you want?”

my father asked in a trembling voice.

“Him,”

the Quendi answered, looking past my father and pointing straight at me.

“I came to buy him.

These golden coins should be more than sufficient.”

I gasped and thought my heart might stop.

“No! Don’t take it, Father! Whatever you do, step away and close the door!”

My father and the Quendi both turned to look at me.

The Quendi soldier looked surprised and forbidding, as if not understanding how I dared enter the conversation at all.

As for my father, he still looked dazed, not fully awake.

“It’s a good price,”

the Quendi said, shaking the small leather purse and ignoring my interruption to address my father again.

“The boy does belong to you, doesn’t he?”

“Y-yes, Pavel is my son.”

“Then take it.”

My father reached for the purse, opened it and poured out at least ten golden kopeks into his palm, some of the money spilling and falling to the floor.

I watched a coin roll across the floor toward me and took a step backward before it reached my bare toes, heartsick and shaking my head in disbelief.

“You’ve accepted the coins, so the boy is mine.”

The Quendi held out a gloved hand to me impatiently.

“Come now.”

I shook my head violently and raised the stick I already held in my hand, intending to strike him with it if I could.

“Come, I said,”

he ordered imperiously, “or I will kill this man.

He has taken my coins, and we have struck a bargain.”

My father fell backward and whirled to look at me, his eyes wide with terror.

“Pavel, please! Don’t fight him—h-he means it.

Look at his eyes—he’ll kill me!”

The Quendi stood, still as a statue, but I could see the wicked long sword strapped to him, and I knew he wouldn’t hesitate to do as my father feared.

He’d probably finish the job by killing all of us, so I lowered my stick and with a shaking hand, shoved my hair back off my face.

“All right, then.

I’ll come.

But you must promise to leave the rest of my family alone.”

The Quendi stared at me a moment and then inclined his head once.

“Very well, though the bargain has already been struck.”

He shook the hand he held out to me impatiently.

“Hurry now.

We have far to travel.”

“I-I have to get my things.”

“Now!”

the soldier shouted at me, so I stepped toward him with bare feet and only the clothes on my back, and with one last, despairing glance at my father, I took the soldier’s cold, hard hand and followed him out into the snow.