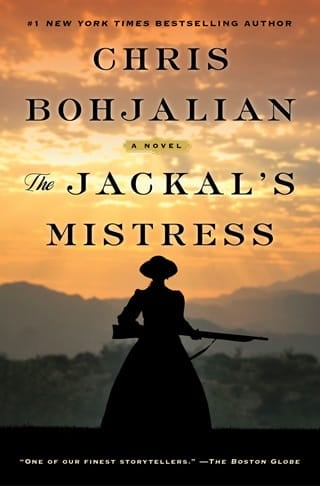

The Jackal’s Mistress

Chapter 1

1

She took the carving knife from the pumpkin pine table and pointed it at the stranger, the handle hard in her hand. He was not young: she appraised him to be just the far side of forty, at least a decade and a half her senior. He had deep bags beneath eyes the color of cornflowers and crow’s feet around them so dark they looked dug into the skin or drawn with a pencil. Though he was wearing Confederate uniform trousers with suspender buttons inside the waist and a forage cap awash in high-summer dust, she could tell he wasn’t part of the Army of the Valley. At least not anymore. He was alone, and when he exhaled, he perfumed the kitchen with the scent of whiskey—which in itself didn’t suggest he wasn’t a part of the regular army, but it was barely nine in the morning, which did. He had neither pack nor kit. He hadn’t a rifle. From the window near the table, she had seen him limping along the path that led to the gristmill, and now here he was. Inside her house. He hadn’t knocked. Just climbed the front steps, direly in need of a fresh coat of paint, like so much else around here, and pushed open the front door into the main room and kitchen.

He held up his pistol. “Lady, I don’t mean you trouble, and I will only shoot you if you come at me with that knife. I am in no hurry to shoot a pretty girl.”

“My man will be back any minute,” she said, hating the quiver she heard in her voice.

“No. He won’t.”

She froze, their eyes locked. Had he killed Joseph? It was possible. Joseph was sixty, at least. He was strong and capable, the reason she could still manage the gristmill and feed herself and her niece and Joseph and his wife. But she couldn’t imagine how Joseph could defend himself against a white man with a gun.

“Are you with John Mosby?” she asked. She believed he probably was, but now had deserted even Mosby’s partisans, or been exiled by them. A brigand or straggler. Or—the term masking the utter reprehensibility of such dereliction and betrayal—a blackberry picker.

“I am.”

“Why aren’t you with them now?”

“Because I’m here,” he said, which wasn’t an answer. Moreover, being with Mosby during daylight was never likely. The guerrillas melted into Northern Virginia during the day, blending in with the community. The Yankees couldn’t defeat Mosby’s Rangers because they couldn’t find them. And you couldn’t beat an enemy you couldn’t see. His eyes moved slowly around the room, pausing at the slab of cooked ham on the table. The meat was a gift from neighbors, the Crawfords, who had killed their last hog before leaving Berryville and heading further south. She hadn’t had ham in months. She hadn’t had meat in months.

“If you go, you can take the ham,” she offered.

“If I go? Now why would I want to go, miss? I think it might be nicer to stay right here, where I won’t get myself kilt. Here, I can avail myself of your company.” Then he smiled, a lopsided grin, and he was upon her, dodging the knife she thrust at him, the blade getting caught in the billowing cotton of his shirt, and he was hurling her to the floor, the back of her head hitting the boards with a thud that stunned her. Left her breathless and dizzy. He tossed the knife toward the unlit lantern that sat by the stove. Then he pinned her neck to the floor with one hand while reaching up and under her dress with the other, his fingers clawing their way through her petticoat and drawers. She tried to roll away, but he was heavy and strong, and it was as if her muscles had palsied. She wasn’t sure where his pistol was now.

And then a shovel slammed down onto the back of his head, the metal blade a paddle, and first he fell onto her, dazed, but he rolled over and bolted upright onto one elbow. There, standing over them, was Joseph, gripping the shovel before him as if it were a musket with a bayonet.

When the intruder saw Joseph, he rubbed the back of his head, saw the blood on his fingers, and said, “Put that down, boy.”

“Move away from the lady,” Joseph ordered.

“Boy,” he said again, the ugly tone of a fallen patriarch, “you just got yourself a noose. Guaranteed. Hitting a white man with that shovel? Yer as good as dead.”

The invader was moving his arm now, and she saw the Colt on the floor. Before he could grab it, however, Joseph took the shovel and jabbed the blade as if it was indeed a bayonet into the invader’s throat, just below his jaw, thrusting it so hard that he snapped the man’s neck, the gash spraying blood onto her face and dress, and sending him onto the wooden floorboards on his back. His eyes were open when she looked down at him, but they fell shut fast and his breathing seemed to stop long before the bleeding.

She had not forgotten her husband’s face, the deep cleft in his chin, the eyebrows so pale they disappeared in the long days of summer. She had not forgotten the feel of the stubble on his cheeks or the unexpected softness (and blackness) of the hair on his chest. But the memories were like the steam off the river when the weather changed: real but something she could no longer grasp. If she were a painter, which she was not, how would her portrait of him have differed from the man she married and whom she recalled loving with a fire that would have made her blush if she ever tried to give it words? Once there had been a tintype, taken for no other reason than that all the men had posed for them when they signed up, including her older brother, but the chemical fixer, potassium cyanide, had been defective and the image had deteriorated days after Peter had left the Valley.

His voice had faded, too. His laugh. She conjured them in her dreams, but when she struggled in daylight to manage a gristmill, work that was never among her labors in even her nightmares, she could not hear him. She remembered his words, but the inflections, the ripples of bemusement that marked them, were out of reach when she was awake.

What remained most real was the feel of his arms around her, the way in bed she would curl into him and he would cradle her, an arm under her knees, her head on his shoulder, and they would talk of tomorrow and children and traveling the Mississippi from Memphis to New Orleans. Perhaps a grand tour that would take them to the ocean, where they would visit Charleston and Savannah. The world was bigger than what had been his father’s gristmill or her father’s law practice in Charlottesville.

There were days when she supposed she never would see either the calm waters of the Gulf or the waves that she had heard marked the Atlantic, because she feared she would never see Peter Steadman again. Her prayers had been unanswered for so long that she no longer bothered to pray. She categorized this as a personal failing: the Bible was clear. Lamentations. But prayer? She no longer had the time. The world, most days, was a dour place, and if she was going to shoulder these ceaseless burdens, she would do it with ferocity and cracked skin on her fingers, with broken nails and a lower back and shoulders that ached. She would manage.

No cause for alarm.

An expression Libby Steadman’s father had used when she was a child. It had comforted her when she was young, though, the truth was, growing up there seldom had been cause for alarm. These days? The last three and a half years? There had only been cause.

As late as the spring before last, there was a Union garrison no more than four miles away with easily a thousand Yankees. There were another six thousand holed up in forts in nearby Winchester, a town that seemed always to be changing hands, control swaying back and forth like a pendulum. The Yankees left her alone, and the few times she saw Federal soldiers, they were civilized. But until General Ewell sent them all scurrying back to Harper’s Ferry, clearing the Northerners out on his way to Pennsylvania in June 1863—routing them over two days and a night—she awoke each morning expecting to see Peter’s and her land a battlefield. It never was, thank God. Since then, most days (but not all days) this part of the Valley had been back in Southern control, where it belonged. Still, just last week there had been a skirmish at Smithfield Summit, a hill visible from the village of Berryville.

But that control also meant that her mill had been beholden to the Army of Northern Virginia, and they swallowed whole, a great leviathan, whatever flour she and Joseph could produce. For now, they’d let her keep two plow horses, a cow, and some of their chickens, but it was only a matter of time before they confiscated them, too.

Today she had worked alone inside the gristmill since just after first light, the Opequon River high and loud because of the rains, the air inside—in the shade, amidst the stones, some darker than thunderclouds—cooler than outside. She had spent the last hour downstairs pulling a muculent paste from the turbines, a plaster of leaves and twigs and mud that sluiced its way down the raceway and into the mill, and the sleeves of her dress were wet to her elbows and her fingers were cold. This was not work that she had ever envisioned would be something she could—or would—do. She barely knew how to plant a kitchen garden when she and Peter had wed, and though she approved of his decision to free his family’s servants, she was grateful that two had chosen to stay on because she didn’t know how else she would have managed when the war had come and Peter had left. The pair, a husband and wife, lived now in what had been the overseer’s place, four rooms on two floors. The overseer had skedaddled as soon as Peter had freed the family servants: Peter had no interest in managing a farm with slave labor. He was confident that with a gristmill in this corner of the Valley, he could make a good living capitalizing on the needs of the neighboring plantations, and no longer have to work to maintain the sprawling fields of corn, barley, and wheat on his family’s land. He’d planned to sell the acreage and the six two-room huts—the slave quarters, now empty—but then came the war. After the war, very likely he would.

Assuming he returned, which daily had grown from expectation to chimera.

Now she was beside a first-floor window in the mill, the glass long gone, the revolver clutched in both hands. It was a six-shot .44-caliber Colt that had belonged to one of Mosby’s rangers, and it was her freedman, Joseph, who’d killed him with a shovel when the bastard had had her pinned to the floor in the kitchen and was struggling to pull up her dress. That had been a week ago, and ever since then, she and Joseph and Joseph’s wife had been expecting either more of Mosby’s men or even a detachment from Jubal Early’s army to search their property. They wouldn’t suppose that she or Joseph had killed the soldier or partisan, at least not at first; they’d be looking for a deserter, assuming either that he was hiding here or that she was harboring him. The trespasser had been alone, but he still could have told someone in which direction he was going or been seen by Libby’s nearest neighbors, the Covingtons, a mile and a half to the east on the Berryville Road. She and Joseph had buried the body as deep as they could in the brush at the edge of the south woods, far from the two horses and their last cow, Joseph remarking as they worked that they would actually have been better off if the bluebellies had arrived and there’d been a skirmish with the nearby Confederates: they could have left the corpse among the dead. Let folks assume he had died in battle.

It seemed that moment of reckoning had now arrived. No cause for alarm? Of course, there was. There was always a reason to fret. Even as a little girl, she had thought the idea there was a divine presence guiding the world suspect. This autumn, years into the war, her husband lost in a Union prison for fifteen months—perhaps, by now, dead—it was clear to her that there wasn’t.

As soon as she’d spotted the three cavalry soldiers galloping across the meadow where her own two plow horses were grazing, she’d grabbed the pistol off the ledge. The men were wearing nearly identical gray slouch hats with braiding the color of yellow squash around the crown, but only one was dressed in a full Confederate uniform. The other two could have been farmers with Confederate hats. She was relieved they weren’t Federals, but until she knew why they were here, she wasn’t about to put down the gun. She didn’t figure she could count on the miracle of Joseph appearing out of nowhere a second time and rescuing her. He was in the barn, repairing a wheel on the wagon. Their last wagon. Their only wagon. His wife and the girl, Libby’s twelve-year-old niece, were at the house.

The horses stopped outside the building and she listened to the men’s conversation.

“Who’s running the mill?”

“No idea, sir, since Steadman’s in a prison camp somewhere.”

“Or dead, in that case.”

“Yessir. Very possible in one a them camps.”

“Maybe his servants? Maybe his wife?”

“Could be.”

“Let’s go to the house.”

She had heard enough: the last thing she wanted was for them to go to the house. Joseph’s wife and her own niece would be easy pickings if these men were pillagers. And if they were searching for the man Joseph had killed, then she was prepared to lie her way through this if it meant that she could send them on their way. Moreover, at least one of them knew enough about her husband to know he was a soldier who was captured, and that was promising. That gave her some assurance. Perhaps even comfort. She lowered her arms, relaxing, and peered through the empty window frame. “Hello,” she said. “I’m Libby Steadman. Do any of you know my husband? Peter Steadman? He was in the Second Virginia. Captured at Gettysburg.”

As one, they doffed their hats when they saw her, but it wasn’t merely, she knew from experience, because she was a woman. There was a deep reverence for the Second Virginia in the Valley, because it had been part of the famed Stonewall Jackson brigade. Jackson had died from wounds at Chancellorsville in May 1863, shot by Confederate sentries who had mistaken the general and his staff for Union cavalry. While the rest of the South mourned the man, convincing themselves they might have defeated the Yankees two months later at Gettysburg if he’d survived his wounds, all she thought now when she recalled Jackson’s death was that, perhaps, her own husband might never have been captured if there had been a better man commanding those boys.

The solider in full uniform continued to hold his hat in his hand as they spoke.

“Ma’am,” he said, “I’m a grandson of one of your neighbors, Leveritt Covington. I’m Henry Morgan. Sixth Virginia Cavalry. Colonel Harrison’s. I don’t know your husband, but my grandfather says mighty kind things about the man.”

She studied him: yellowish beard, tall in the saddle, eyes that almost were black. One of the other two was scrutinizing her horses as they grazed in the distance. Morgan had blond hair the same color as hers, and almost as long. These men were definitely regular army, not Mosby’s partisans, and she felt a great waterfall of relief. There were people in the Valley who revered John Mosby’s men for their daring—their exploits in the small hours of the morning behind Union lines were legendary—but the one ranger who’d set foot on her land had been a drunk who’d attacked her.

“Have you heard something about him? Please tell me you have. I haven’t gotten a letter in months. I don’t even know if he’s still alive.”

“No. I’m sorry. All I know is what my grandfather knows—which is less than you know, I’m sure.”

She took this in. “Wait one moment,” she said, and she walked from the window to the door, emerging from the cool of the stone building into the sun. “Well. How can I help you?”

“You can begin by taking your finger off the trigger and putting that gun away,” said Morgan. “We’re not a threat.”

She glanced at the pistol, surprised it was still in her hand. She smiled and tucked it into the sash she wore around her waist to keep the dress in place when she worked the mill. She and Joseph had buried the dead man’s holster with the corpse. The gun was one thing, but they wanted as little evidence as possible that the fellow had ever been on the property.

“You hoist them bags?” asked one of the other men. There were a dozen bags of flour under an awning that she and Joseph had ground yesterday. An army quartermaster was due tomorrow to retrieve them.

“I can. I do.”

“Little thing like you?”

There was something dangerous in the short sentence. She responded with a firmness she wasn’t feeling. “No choice these days. Someone’s got to feed the army.”

“We thank you,” said Morgan.

“Tell me: Why are you here?”

“Union Army’s approaching Berryville again,” he said. “We’re scouting for ground.”

She absorbed this. She was relieved they weren’t looking for the dead man. But the idea they were reconnoitering this part of the county was ominous. “The battle will be brought…here?”

“Don’t know that. And, looking around, don’t think so. At least not if we fight where we choose. But I recalled the Covington property runs along the river, like yours, and I wanted to see how far the ridge stretched beside it.”

“Not very far. There’s just Walker Hill,” she said, nodding in that direction.

“No. I expect you’ll be lucky. But the Yankees now are different from the Yankees we whipped in these parts last year. There’s more of ’em, and they don’t just want to fight us. Rumor is, they want to burn this valley down. Turn it all to campfire ash.”

“I know. I’ve heard those rumors.”

“Now, the army does need hands. We need all the hands we can get. Even if you do, as you say, lift those bags, you must have help. How many slaves you all have here?”

“None. I have one freedman and his wife. I have my niece. It’s just the four of us.”

“Freedman. We’ll still take him.”

“He’s over sixty.”

“If he can help here, he can—”

“And if you take him, Mr.Morgan, it will be that much harder for me to feed you. He runs the wheels, he gets the grain into the hopper and the garner bin up top. You take him, next time your quartermaster comes through, he’ll leave empty-handed.” She hoped that she sounded reasonable, not antagonistic. She did need Joseph. She needed Joseph and Sally and even her niece, Jubilee. She needed everyone. Her husband had freed Joseph and Sally in January 1860, a few months after his father had died and he’d inherited the mill. His father had owned twelve slaves, and Peter had freed them all. Only Joseph and Sally had chosen to remain and be paid whatever wages Peter could provide. She and Peter had married a few months later, just before her twentieth birthday. Then, barely a year after that, had come the war, which led to a deeper, more pronounced level of need: Joseph and Sally were now her family. Since her husband left, she had had almost no one but this older couple with whom to commiserate and, on occasion, to laugh. To play cards with and cook. Her life would have been unbearably lonely without them.

The fellow put his hat back on and rested both hands on the horn of the saddle, digesting what she had said. “It’s Lieutenant Morgan,” he corrected her, his tone colder, and she understood that he had heard mostly antipathy in her response. “Not Mr.Morgan.”

“Lieutenant,” she repeated obligingly.

He stared down at her from his horse, and she was aware, for the first time, that the day was utterly windless. The moment when no one spoke stretched long, a lanky braid. Finally, the lieutenant informed her, “Ma’am, we will be back—when we need something. Or your…freedman. Or those horses. We know where you are.” Then he turned his own horse and spurred it across the field toward the road, his two men studying her—not leering, this was different, they seemed more puzzled by her presence, as if she were a flower too rare for this valley—for lingering seconds before following him.