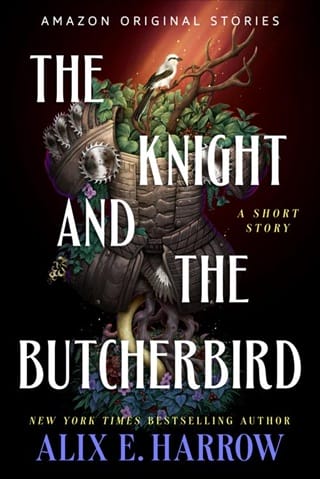

The Knight and the Butcherbird

Start Reading

O nce upon a time, a knight came riding into the holler.

This was early August, three hundred and some odd years after the apocalypse, during one of those heat waves that dries up the creeks and kills the corn. Only the cicadas were happy, crooning like a funeral choir from the trees.

We waited for the knight in the mouth of the valley. The grown folk gossiped. The kids lay in their shadows, cross and sticky. I stood among them like a tumor at a birthday party: silent, uninvited. Likely fatal.

Around me, a gasp. The knight, riding through the heat haze at last.

It didn’t matter that his armor—sewn of fine black tire treads, steel corded—was cracked with age, or that the lapped saw blades of his pauldrons were badly rusted. It didn’t even matter that he was old—crazy old, maybe even fifty.

He was a Knight of the Enclaves! A legend! A hero, probably! He was tall, raised on multivitamins and clean meat, and he wore a band of ancient bullets across his chest! Even I felt a faint, stupid awe.

Laurel Boss swept her cap from her head and said, in polite commontongue, “Welcome to Iron Hollow, stranger. Wasn’t sure my message made it, or if anybody would answer it, but I’m damn glad someone has.”

The knight said nothing.

Laurel cleared her throat. “Your name and enclave, sir?”

But the knight wasn’t even looking at her; he was looking up at the sky, where the sun hung white and awful. He whistled once, sweetly, and a hawk’s cry answered him. The knight lifted his right arm at a funny angle, as if asking a girl to dance.

Then: a sleek feathered body, falling fast. The sudden snap of great wings. Talons curling around the knight’s fist, biting deep into the black rubber vambrace.

I knew the name of every bird along the Red River, but not this one. Too dark to be a red-tailed or a goshawk, too heavy to be an osprey, too big to be anything else. It wore fine leather jesses, caught now in the knight’s glove, and an odd little hood with smoked-glass lenses over each eye.

It was as the knight turned to speak softly to his bird that we saw the scar: a knotted white welt that stretched from clavicle to temple. The hinge of his jaw was misshapen, and his left ear was missing entirely.

Another gasp. This time, I gasped with them.

Even here in Iron Hollow, way up the Red River, two hundred miles from the nearest enclave, we knew his story. I knew it better than most, as a Secretary: Once upon a time there was a brave knight who was set upon by a demon. In the battle he lost his left ear—and his young wife. The knight vowed on her grave to rid the world of demons. He never again returned to his enclave, but scoured the outlands ever after, a hawk on his arm and hate in his heart. The hawk, they said, was specially trained to hunt demons.

Laurel Boss swore. “I’m sorry—I didn’t recognize—I mean, if we’d known—”

But Sir John of Cincinnati said, in the stilted, old-fashioned manner of the enclaves, “Be easy, good lady.” He had a good voice, carrying but calm. I felt his authority settle gently over the town, tucking itself around us like a quilt in winter. “I am come to slay thy demon. Only tell me where I may find it.”

“We don’t exactly know, but it’s not far.” Laurel spoke quickly, with relief. Boss was never an easy name to bear, but this summer must have been hell: the heat, the demon, the death of the beloved old Secretary and the bad attitude of the new one (me). “There’s been a few sheep taken, and the iron crews are too spooked to work.”

“Who saw it last?”

“Well—that’d be Shrike. Shrike Secretary.” There was, for the first time, a little hesitation in her voice, as if, in saying my name, she’d remembered May’s. It wasn’t possible to separate the two of us, even now.

The townspeople pulled away from me, so that I stood alone.

Sir John saw me, and I knew what he saw: Another underfed outlander girl, thin and brown in homespun coveralls. Pretty, in the way that anyone who isn’t sick is pretty, but not striking; clever, to be a Secretary at seventeen, but not remarkable. May had always said my name suited me: no one ever notices a shrike.

The knight smiled kindly down at me. “Come forward, Lady Shrike. I shan’t bite. Now tell me: Where did thou last see the demon?”

I made my chin tremble, the humble country girl overawed by the grand enclave man. “North, sir, not far from the dam,” I lied. And then—for one clumsy, careless second—I met Sir John’s eyes.

He blinked. “North,” he repeated, mildly, but of course he didn’t believe me. In my eyes he’d seen the truth: that I hated him, and would kill him if I could.