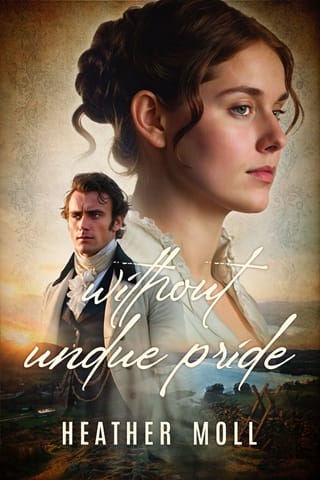

Without Undue Pride

Chapter 1

4%

Without Undue Pride

Chapter 1

4%

CHAPTER 1

January 1811

London

What a pitiful situation,” Lord Fitzwilliam muttered, taking a long drink from his glass. “The foolish boy has to go through with it now.”

Fitzwilliam Darcy stood by the fireplace, gazing into the burning coals. He was uncertain why his uncle had invited him to join Lady Fitzwilliam and their eldest son at the signing of the settlement papers, or even why he stayed with the dour trio. The young lovers had already left to make the rest of the preparations for their approaching union.

The short meeting between the earl and the father of the bride to arrange the money matters had been a tense affair. His lordship refused to give his younger son anything if he married so far beneath him, the son had nothing of his own to settle on his future bride, and the lady’s father offered only one thousand pounds on the death of himself and his wife.

“My son knew his father would not open his purse strings if he formed such a connexion,” the countess cried, “and I would no longer pledge him part of my jointure, either.” Lady Fitzwilliam had been glowering but silent until now. “And he still sat there smiling as he signed the papers. The father must be triumphant to have secured such a match.”

Darcy thought the father a fool for not asking anything for his daughter. His cousin had only a few hundred a year as a colonel in the Foot Guards, but Lord Fitzwilliam had a splendid fortune. It would not have been unreasonable for any father to insist such a man settle a few thousand pounds on the new bride, or at least on any children she might have.

This bride’s father did not even give her anything for her own expenses.

“You did give my brother something,” Lord Milton quipped from his corner of the room. “You will generously present him with plate, linen, and china. Goodness knows the bride is too poor to bring anything of quality of her own.”

Darcy supposed his cousin Milton had come to the signing to try one final time to convince his younger brother not to go through with the wedding. Perhaps that was why his uncle had invited him, too. Darcy scoffed as he kept his back to the room, his gaze still on the flickering flames. How little they understood Fitzwilliam’s resolve. As easy-going as he was, once he decided on a course of action, nothing would keep him from his chosen path.

“What need will he have of linen and plate when he returns to Spain?” Lord Fitzwilliam said. “His battalion deploys again in a month. It is the only reason he is marrying the first pretty face he laid eyes on after he returned to England.” Darcy heard him take another drink. “Damned impulsive boy. She will do nothing for him.”

“She is a mere milk-and-water girl,” his countess agreed. “Hardly fitting for the fashionable world. My son is much to be pitied.”

“He might at least have had money if he chose among the first women of his own rank,” Milton said. “She is pretty enough, but he will bitterly regret his hasty marriage. ”

Darcy agreed in his own mind that it was hasty. His cousin had met this girl, up from the country to visit an uncle in trade, at a public ball days before the new year, and here he was about to marry her by the end of January. The First Regiment of Foot Guards second battalion was returning to the east coast of Spain next month. Knowing one might die reinforcing a garrison currently under siege was enough to make an already spontaneous, unconcerned man act imprudently.

“Last evening was dreadful,” his aunt cried. “I thought the mother would be eat up with the vapours the way she carried on. You know she was tallying the cost of the furnishings and wondering how soon her daughter would have money to spend. She gets nothing!” Lady Fitzwilliam must have risen to pace. Darcy heard her voice move closer and then farther away. “But for fear of the consequences, I would hardly scruple to murder that girl! She has ruined my son.”

His uncle sighed. Darcy supposed a disapproving look accompanied it. “Her entire family is a set of low, impertinent people. But the girl can conduct herself properly.”

Darcy had only met her once before today’s settlement signing. She was nineteen, tolerably pretty, with a lively disposition. In some ways—and with a better situation—she might have been a good match for his cousin. They were both quick to enter conversation, both energetic and fond of people. But Darcy knew if not for his imminent return to Cádiz, his cousin would never have thrown away an inheritance and his family’s approval for a poor girl he had just met.

“Not one good thing can come of this,” Lady Fitzwilliam went on. “I will never speak to my son again!”

That was likely true. His aunt was a woman who spoke in absolutes. His uncle was a more genial man, but a lifetime in Whig politics made him balance holding the line and offering conciliatory motions. With his wife adamant, he would not approve of his son’s unwise choice.

There was a pause before Lord Fitzwilliam said quietly, “He might have a son. ”

A long silence stretched, and Darcy slowly turned round. His uncle looked pensive, perhaps a little melancholy. His aunt pursed her lips in disgust, and Milton crossed his arms over his chest and looked away.

“Well, a son would be heir presumptive after Milton,” Lady Fitzwilliam said crossly, “but his mother would be a low-born plebeian. Milton and his wife have only been married five years. It is far too soon to discount dear Lady Mary.”

“The next heir to that ancient peerage will be of my blood, not my brother’s,” Milton said in a grim voice. He held his current courtesy title a little too dear for Darcy’s liking. He would be insufferable when he actually inherited the earldom. “Mary could… There is still time, so do not suggest my brother’s child with that woman will inherit.”

Lady Mary had presented Milton with one child, and then, much to their joint regret, a stillborn child had followed. Darcy interpreted the whispers, social withdrawal, and averted looks to mean that she had miscarried several times since. It was a great deal of loss for only five years, and for a woman who had only one role as far as Milton was concerned. That the children born had been girls would also weigh heavily on him. Being the next Earl of Fitzwilliam and heir to all the estates annexed to that title was of the utmost importance to Milton—surpassed only by his need to pass them on to a son.

Milton heaved himself from his chair. Making his way to the port, he said over his shoulder, “What are you standing around for, Darcy? You were completely useless.”

“Useless?” he repeated. “I would be offended if I had any idea why I was called upon to attend.”

“You did not even try to dissuade him. If he was going to listen to any of us, it might have been you. Heaven knows why,” he muttered.

How was it possible that one brother was his dearest friend, and the other he could hardly stand to share a room with? “Does Fitzwilliam have a great natural modesty, a stronger dependence on my judgment than on his own? You know how he is. Once he decides, he is immovable. ”

Milton took a long swallow and gave an affected, casual shrug. “Do you even care about the quality of the Fitzwilliam line?”

“I pointed out to him the certain evils of his choice. I described and enforced them earnestly a week ago when he told me he proposed.” He had known why his cousin did it: he was returning to war, and here was a pretty girl who admired him. “I could not honestly say that I thought his chosen bride was indifferent to him, and that was the only thing that might have dissuaded him.”

“But you cannot approve of her,” cried Lady Fitzwilliam. “She is poor, unconnected, and her family cannot behave with propriety. It is a humiliation.”

“I am disappointed,” he said, trying to keep his patience. “It is an unsuitable connexion, and one that brings him no fortune. It was bad enough knowing the uncle was in trade, but at least the aunt and uncle had a sense of decorum.” When the mother and father and sisters came to town, their behaviour had appalled everyone, even Fitzwilliam. It was only a slight consolation that the future bride was nothing like them. “But he has made his decision. The papers are signed, and now all of you have a choice to make. I have made mine.”

He bowed and moved toward the door. From the other side of the room, his uncle said after him, “What choice is that?”

Darcy turned around. “He will marry her in two days. She will be his wife , and due all the respect and notice as the wife of the second son of an earl deserves—what your son’s and brother’s wife deserves. My opinion no longer matters. So you can all choose to never speak to him again. I, however, will not lose my closest friend over this.”

“Darcy, you can stop looking,” Fitzwilliam said as they loitered by the church door. “They are not coming. I have made my peace with it, and so should you.”

How could his cousin be calm about his parents and brother refusing to attend his wedding? He had hoped they would choose differently, but he really ought not to be surprised. He was only saddened .

Fitzwilliam, however, looked buoyant.

“I cannot believe you had me here half an hour early,” Darcy muttered, checking his watch. “You are late to everything. The clerk is not even here yet.”

There was a long pause before his cousin asked, “Do you not like her?”

His tone caught his attention. He had known how much his public appearance of approval meant to Fitzwilliam. He had not realised it mattered that he actually like this woman.

“I like her well enough,” he said with a shrug. “You know my concerns. I have been honest, but I am here.” How wretched that he was the only one to come. “And I will always admire and respect Mrs Fitzwilliam.”

“Do you promise me that?”

Now his cousin sounded worried. “Have you ever doubted my word?” Darcy asked. “I have never had reason to doubt yours, so I hope those are only wedding nerves talking.”

“No, I just—I have nothing to leave her, and my parents choose to give her nothing, and her father cannot. If anything happens to me…” He forcibly eased his countenance. “She will need a man to look to for guidance, to manage her business affairs, to see that she has money and whatever else a war widow is due.”

Darcy’s stomach clenched at the thought of his cousin not coming back from the peninsula. “Mrs Fitzwilliam can rely on me.”

“I am disinherited now. I cannot jointure a wife out of an estate or an inheritance I will never possess. I do not want my wife to have to turn to Milton or my father. They will never provide for her or offer her sound guidance. You would act in her best interests.”

Darcy solemnly agreed. “Time will do much for your finances,” he added in a reassuring tone. “You are only thirty, and can save and invest wisely.” It was not impossible that in ten years their situation would be improved, especially if Fitzwilliam stayed in the army. “Mrs Fitzwilliam might end up well provided for through your own means. ”

“To that end, I have put my funds in a Portsmouth bank. All the soldiers are investing in Cattell and March, and it will be convenient for while we are there.”

His battalion would be there briefly before deploying to Cádiz. Darcy wondered if Fitzwilliam struggled to believe he must return to the battlefield.

“All of it is in a country bank? They tend to be over-traded and give reckless advances. So many of them fail. Will you keep nothing in the Bank of England?”

“I have little to invest in the first place now,” he said with a wry look. “Better it all be in one place. It shall all work out.”

Darcy opened his mouth to say perhaps his parents would come to accept his choice and provide them some money, but he changed his mind. His cousin deserved better than false hope.

They were silent for a while, pacing by the church door. Fitzwilliam asked, “Do you have the ring?”

Darcy smiled at his cousin’s worry and patted his coat pocket. “Have you revised your will?”

Fitzwilliam waved a hand. “I will get around to it. She has the settlement papers, and it is not as though there are children yet.”

Darcy only shrugged. He would have revised his will the day he was engaged, but he was done advising, cajoling, or persuading.

“While we have this moment alone,” his cousin began slowly, “I have a request for you while I am gone.”

Gone, not “in Spain” or “defending a garrison against an ongoing French siege.” “Is it to drink and dance more? Because I cannot promise that, even for you.”

Fitzwilliam chuckled. “No, I have no hope for that. But I want you to be more patient with people, especially with those outside your circle. You never give yourself the trouble to talk, or even to be kind, and I will not be here to smooth the way for you.”

Darcy tilted his head in confusion. “You make it sound as though I have an unyielding temper, the cruellest man on the earth.”

“Cruel?” he repeated, surprised. “Never. Unyielding? Often.” His cousin gave him a pointed look. “Darcy, I will be gone. No one will help you talk to strangers or tell you to smile at a person rather than scowl. No one will stand up to you but me. You can be arrogant and, forgive me to add, a little selfish.”

“You think me selfish?” Here he was, in defiance of his family and good sense, to support his cousin’s foolish marriage, and his cousin thought him selfish?

Fitzwilliam clapped him on the shoulder. “You are my closest friend. There is no one on whose loyalty I rely more. And your wealth and position give you a sense of improper pride that can make you unlikable. I want people, friends and strangers alike, to see the Darcy I know, the one who is here with me today.”

However little he agreed with this assessment of his character, today was a day to be agreeable. “I promise to be more patient and affable, but once you come home, I expect to return to thinking meanly of new people and relying on you to ease my way with strangers.”

His cousin laughed. “Thank you for everything, my dear Darcy.”

Darcy nodded, his throat closing and a burning sensation pricking the back of his eyes. His dearest friend was returning to war. Where were the words to say everything he felt in his heart? Probably hidden behind all the fear that his cousin would not return.

The church door finally opened, and the vicar motioned them inside. Fitzwilliam practically ran to the altar. He was not at all bitter at being disinherited, at being a stranger now to his parents and brother, at being thought a fool by good society. That girl was enough to make him happy, so Darcy had to accept her.

The ceremony took place as they always did. The bride was attended by the least objectionable of her sisters, and her father gave her away. Darcy handed over the ring and payment at the appointed time. The bride bore away the bell on the occasion, outshining any bride Darcy had seen, with her bright eyes and wide smile.

He had no objection to a lady seeking riches or rank—it had only surprised him that Fitzwilliam had succumbed to it. But her visible admiration for Fitzwilliam told him she was not a fortune hunter. And that she had married him even after his parents disinherited him spoke to her character.

Along with the vicar and the bride and groom, Darcy and the bride’s sister went to the vestry to witness the signing of the register. When that was done and the copy made and signed, the vicar handed him the marriage lines. His final responsibility in this ceremony was to, in turn, give it into the keeping of the bride, which would be Mrs Fitzwilliam’s property and proof that she was married.

He looked at her closely for the first time. She was lively and quite pretty, and his rather plain cousin’s vanity had been flattered in a vulnerable moment after he learnt he was returning to war. Still, she loved him—and that was all that mattered now.

She was giving her new husband an admiring look as he spoke with the vicar, and Darcy had to lightly touch her hand to catch her notice. She turned, and their eyes instantly met. He felt a jolt of awareness—he dared not call it an attraction—and his heart beat a little faster as she blushed and held his gaze. He felt an inexplicable bond between them he had not felt the other times they had met.

Strange things may be accounted for if their cause was properly searched out. The emotions of the wedding day, and his loyalty to and friendship with his cousin, must have shifted those same feelings toward his cousin’s new wife.

She puffed a faint breath of air and blinked her eyes, taking the marriage lines and holding them close. He must have imagined the intensity of the look they exchanged.

“Thank you, Mr Darcy. And may I say, I am quite glad to see you today.”

He knew she meant she was glad his cousin had a single friend to stand by him. “My friendship with Fitzwilliam trumps all else.”

Mrs Fitzwilliam held out a hand as the vicar gestured they might return to the chapel. “I hope you and I will also be excellent friends.”

Darcy took her hand, his heartbeat now steadier than it had been a moment ago. “I promise to be your sworn friend to the end of my days.”

February 1811

Portsmouth

Elizabeth Fitzwilliam completed her final daily walk along the ramparts. The town was typically filled with sailors and the harbour full with ships, but now that an entire battalion would embark tomorrow, she passed dozens of soldiers on her short way home.

Their temporary lodgings while they awaited deployment to Spain were what most would call cramped, but Elizabeth generously called cosy. They had spent a week in the most private manner imaginable in Portsmouth, without keeping a servant of any kind. Some might say she was a fool to marry under such circumstances, but then those same people would have called her worse had she broken her engagement after her husband was disinherited. His family’s splendid wealth made no difference to her. Her husband had an income from the Foot Guards, and they would make their own way.

Fitzwilliam would be home by now with confirmation if she would be one of about sixty officers’ wives from his battalion allowed to follow their husbands in the wagon train. If she was not, her friend Charlotte Lucas would come to live in Portsmouth with her until her husband returned.

Elizabeth exhaled nervously. She wanted to go to Spain; she only wished it was not so soon. Adjusting to marriage and coming to know a person took time, time to learn their manners and preferences and needs. She was thankful they had this week in Portsmouth, at least. She could not fool herself that while her husband was training troops or commanding a picket line that he would have time for her.

When she entered their rooms, her husband was already there. He answered her unspoken question with an emphatic “Yes!”

Elizabeth heaved a sigh of relief as Fitzwilliam put his arms around her. There was a lottery the evening before a regiment sailed to determine which families could join their husbands. “How grateful I am that we have such luck! ”

He barked a laugh. “I suspect they arranged the outcome for my benefit as a new husband, but I will not complain.”

Elizabeth pressed a quick kiss to his lips and wrote a brief letter to Charlotte, saying she was leaving Portsmouth after all. Her husband followed her to the table and said, “Why did you ask Miss Lucas to join you and not Jane?”

She smiled. “While Jane was in London, she met a friend of your cousin’s, and my mother did not want to impede that relationship. Mary would not be much comfort to me, and the other girls are too young and boisterous. But Charlotte is my closest friend, and we would be good for one another.” Elizabeth folded the letter carefully. “I will write her a longer letter from Spain.”

As she sealed it, her husband said quietly, “Lizzy, are you ready for life as a camp follower?”

“You assure me I will not be in a tent, at least not the entire time, so I will do well.”

“We will be billeted in a home in Cádiz eventually,” he said slowly, “but when we land in the southeast of Spain, you must march with the other followers, the wives, the children, the doctors, the cooks. It could be fifteen miles a day until we get to Cádiz, and you cannot ride in a baggage cart?—”

She silenced him with a look. “We discussed this. I would rather not be parted. And I am ready for an adventure.”

Elizabeth began packing, but she felt Fitzwilliam’s pensive look. It was too late for him to worry about life on the campaign. “I won’t stay behind,” she said firmly. “And not just because there would be no allowance from the army if I stay. I have access to your pay immediately if I go with you.”

“And a half ration a day. A veritable luxury.”

They always had light, friendly talk. Her husband was easy-going, so ready to laugh. She supposed those weightier conversations would come in time.

“The luxuries will be a long time coming,” he said as she closed her trunk. “All of my money is invested in Cattell and March here in Portsmouth. We will eventually do well for ourselves. ”

“Is that wise, dear, to have it all in one small bank?” she asked. “Perhaps we ought to leave a little invested elsewhere?”

He gave her a puzzled look. “I know what is best for us,” he insisted. With a warmer smile he added, “Besides, nearly everyone in my battalion opened an account there.”

His gentle rebuke stung a little. She had expected that she and her husband would make such decisions together. He had lived more in the world, and likely knew more about banks than she, but she had thought her suggestion sensible. She did not know his manner or expressions perfectly yet, but Fitzwilliam looked as though he would not hear her advice.

But what could a new bride do but cheerfully agree? “See, by the time we return, there could be a small fortune for us.”

Fitzwilliam sat on the bed with a smile. “If I do not return, I expect you to marry a fellow officer within a month.”

She laughed and sat next to him. “I hear most war widows on campaign marry again within a week. You should suggest a man now. I want to consider your preference.”

“I will make you a list. In all seriousness, Lizzy, make your way home if anything happens to me in Cádiz. They will not pay to send you back to England, but there are charity funds among the officers for such things. Do not marry just for your own protection to stay in Spain because it would be easier than getting home.”

The thought of losing her charming husband made her throat close. It was a possibility, of course, but now that the moment was at hand, the threat felt alarmingly more real. “You assured me living in the garrison would be quite safe, as safe as one could be in the seat of war.”

“The French cannons cannot reach it. The siege causes more problems to supply lines than it does to life.”

There was a long pause while he looked into her face. “But?”

“But more battles are coming. Women are chattel, Lizzy, and the chattel of the enemy belongs to the conqueror, and some commanders may not distinguish between officers’ wives and female camp followers. Make your way home to your family if anything happens to me— unless you are already madly in love with another officer by the time I die.”

Elizabeth loved to sport with Fitzwilliam, but she wished he would not make light of this. Still, he was the one leading troops into battle, so it was best to talk in the manner he wished.

Giving him an arch smile, she said, “I will do my best to pick one you approve of. Your commanding officer, Colonel Bushkill, is amiable, and Major Hamilton is handsome.”

“That is a good plan; do not allow Bushkill’s age or Hamilton’s wife deter you.”

They laughed together. They were always laughing. When would they talk about their hopes and expectations, their reflections on politics or books? Perhaps those were not wartime subjects.

“With the little money in the Portsmouth bank, my pension, and maybe help from my father, you could be set up.”

Elizabeth shook her head. She did not want him to labour under false hope. They could sport with one another, but she could not lie to him. “I doubt your father will come around, not with your mother set against me. Perhaps your brother would be the one to relent.”

“Never align yourself with Milton,” he said grimly, “especially if we have children. All my brother cares about are his inheritance and having a son to pass it on to. His dislike of me would make him hate having his nephew be his heir.”

Fitzwilliam put an arm around her and tucked her into his side. “If you have need of anything, turn to my cousin Darcy, not Milton.”

Seated as they were, he could not see the hesitant expression she knew her face made. Mr Darcy appeared to be a stern man the few times she had met him, although he seemed to unbend a little at the wedding. He had even smiled at her when he handed her the marriage lines. That moment when they locked eyes almost made her feel as though there was a connexion between them.

Elizabeth laughed herself out of her silly reflections. She reacted strongly to Mr Darcy because his was the only notice she received from Fitzwilliam’s family, unless she counted his mother screaming at her that she had a heart of stone for entrapping a man far above her .

Mr Darcy may have disapproved of her family and lack of fortune, but he had stood by his cousin when no one else did.

She leant into her husband, hoping that he would not soon be married more to the army than to her and that these gentle moments between them would not be lost. “I promise to turn to Mr Darcy if I ever have need of a friend.”