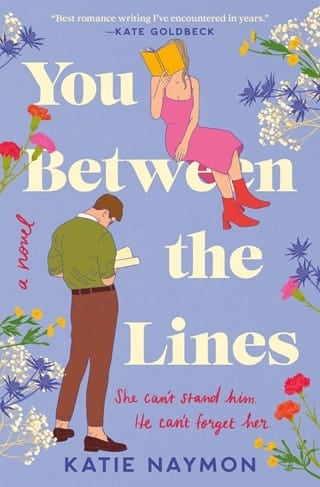

You Between the Lines

Prologue

10 YEARS AGO

W HEN W ILL L ANGFORD DRAGS HIS pen over each line of my poem, slowly, as if to not miss a single word, I feel the movement scraped over my legs.

He’s the kind of student Mrs. Lincoln’s creative writing elective was made for. The class is a big deal to get into. You had to apply with a short story or three poems, and there’s only room for ten students, to create an intimate feel. As one of the only two juniors selected, I feel a need to prove why I’m here.

But Will doesn’t. He’s a senior, the president of the Rowan School Literary Club, the editor in chief of Expressions , our student literary journal, and next semester, he’s graduating and going to Middlebury to study English. Will wants to be a writer when he grows up, and if you know him, you know that .

I want to be a writer, too. In middle school, I won all sorts of local writing competitions. I scribbled short stories under a timer in drafty auditoriums and felt like a pop star when my name was called hours later, accepting gold plastic and certificates like they were Grammys. I liked the way they glinted along my bookshelf’s edges, obfuscating the actual books behind them. I wasn’t the most popular or the prettiest, but I did write Cuyahoga County’s third-best short story for a seventh grader.

Writing’s my escape. As an only child, I never grew up playing house or doctor or any of the other games siblings play together. Instead, I made things up, just for me. And now, while other kids are first-kissing and kicking soccer balls over summer break, I go to creative writing camps, exchanging poems with braces-clad boys who look at me like I’m the kind of girl who knows how beer tastes.

In a poem, I can be whoever I want to be, even if it’s just for six stanzas.

So yes, I want to be a writer. But not the annoying kind. It feels like most writers are very, very annoying—particularly the population of straight, white literary men. The kind that everyone hates but craves approval from anyway. You know the type. The guys with three names—David Foster Wallace, Jonathan Safran Foer. I haven’t read anything by them and I won’t. Maybe because I’m in high school and, quite frankly, have better things to do than read Infinite Jest .

But it’s not just the contemporary guys. I SparkNoted my way through Ernest Hemingway in ninth-grade English. I skimmed The Sound and the Fury and suffered through Madame Bovary (in French, no less). I love reading, I swear. But I’ve never been able to sink my teeth into these lauded literary classics—the ones written by men, the ones set in wartime, with stream of consciousness as their stylistic mode of choice, the poverty and depression of men as their focus. Give me Bront?, Austen, Lorde. John Steinbeck, though? Ralph Waldo Emerson? I’m good.

But Will is different, I’m sure of it. On the first day of this workshop, when Mrs. Lincoln asked who our favorite writer was as an icebreaker, Will said the poet Mary Oliver. Everyone else said Sophocles, Ayn Rand, Charles Dickens. I was going to say Erica Go, a young poet who plays with pop culture, but I got intimidated and lied, saying F. Scott Fitzgerald instead. (I did dress up as Daisy for Halloween, but that’s only because I look amazing in a flapper dress.)

That’s the problem with me. I constantly read the room and cater my movements, words, thoughts, which-comma-goes-where to other people.

Because he’s a year older, I’ve never been in class with Will before. I’ve only watched from afar—Will, making a call for submissions to Expressions during morning assembly, Will, reversing out of the school parking lot, his hand on the back of the passenger-seat headrest. The curlicue of caramel hair he can never seem to get off his forehead, a stark contrast with the perfectly symmetrical bunny ears of his boat shoes, the knot of his tie. While the other popular senior boys are going to party schools for football or planning senior pranks, Will Langford writes poetry in faultless cursive in his Moleskine notebook in a Middlebury crew neck and khakis.

Absolute catnip for girls like me.

Outside of class, we’ve spoken exactly once. It was at this year’s homecoming dance, when my best friend Gen (who snagged the second junior spot in this class) tried to orchestrate a meet-cute by steering me in his direction. I bumped into him mid “Mr. Brightside” and spilled Sprite on us both. He apologized even though it was definitely my—well, Gen’s—fault. He couldn’t even look me in the eye as my hot-pink dress clung to my body, soda-wet and sticky.

“Oh my god, I’m so sorry,” I’d said.

He shook his head. “No, it’s my fault.” He ran his eyes across my body. “Here, maybe paper towels in the bathroom…” He set off in the direction of the accessible bathroom right outside the gym, and Gen violently shoved me once more, to get me to follow.

“I’m really sorry.” I watched soda drip down the chest pocket of his light-green button-down. He handed me a paper towel and we dabbed ourselves, not making anything better.

“I actually…” He looked through the bathroom’s open door toward the mass of students. “I don’t mind the interruption. I’m not sure I can really dance.”

In the yellow-tinged light of the bathroom, his eyes were a choppy mosaic, twinkling with shards of copper, sage, and seafoam.

“I’m Leigh, by the way.”

He nodded. “I know. I’m, uh, Will.”

A wildfire erupted in my stomach. “I know.”

We stared at each other like we didn’t know what to do next. I hugged my arms around me, suddenly cold in my wet dress. How awkward it is to have a body.

“Okay, well. Sorry again.” I smiled, my face heating up.

“Should we, should we, uh—”

A gaggle of freshman girls catapulted into the bathroom for a lip gloss refresh. Will and I walked silently back to the gym, where the music had moved on to Usher’s “Yeah!”

“Should we what?”

But he had already slipped into the crowd. The interaction ended there, to Gen’s dismay.

So last night, when I emailed everyone my poem ahead of class, all I could think about was what Will would write on the poem I’m about to present.

Most of the class is hesitant to critique, even when Mrs. Lincoln reminds us that this is a safe space and constructive advice is always appreciated by the author. But from day one, Will’s comments have been direct and helpful. They’re so good, I feel like he’s reading different works than the rest of us. While I get the shallow stuff, the fluffy layer of foam on top, Will’s able to envision what the writer intended to do and provide notes to help them get there. After each workshop, we pass our comments around the table to the author, and every time I pass Will’s, I see long blocks of cursive in the margins, squiggles throughout stanzas and paragraphs, underlines and exclamation points.

“Go ahead.” Mrs. Lincoln nods at me to begin reading my poem. I glance across the table at Will. He is already underlining, and my stomach swoops in anticipation.

“‘Introduction to Feminist Blogging,’” I begin, and take a deep breath. “‘Step One: Write a think piece / 37 Reasons Why We Need Feminism .’”

Pause. I look up. Everyone is staring at the paper except Will, who is looking straight at me, his hazel eyes dark and unreadable, his hands clasped neatly on his desk, pen down. A current of electricity flashes over my skin with every second of his focus. I cross my legs and then uncross them.

My pause grows, and Gen gives me an encouraging smile. I start reading again.

First comment: Shelton from Arkansas:

Women should keep their legs together , sparking

Guest: Don’t get your panties in a bunch!

Pam1992 informs the group that feminism

just means equality

(that didn’t go over well)

I continue with the rest of the poem, taking idiotic comments from a recent article and pairing them with my imagined “steps” of the woman journalist. Step one, write a think piece. Step two, get doxxed. Step three, get a death threat. I thought it was provocative, and there was so much good material in the comment section, the poem basically wrote itself. I was especially proud of the last line, “Simone de Beauvoir is spinning in her grave,” when I wrote it last week.

“Great, Leigh,” Mrs. Lincoln says. “Now, class, let’s open it up to discussion. What is working well in ‘Introduction to Feminist Blogging’?”

Gen raises her hand first, almost too on cue, but I appreciate it nonetheless. “I think this is such a clever idea, combining the words of female writers with the nasty male commenters. It’s a really cool juxtaposition.” I grin in her direction.

A senior, Michaela, raises her hand next. “I agree. The title pulls you in, and I like how Leigh structured the lines into step one, step two, step three. Like a how-to guide to being a woman on the internet.”

I breathe easier now, but the conversation starts to stall, and Will is still silent. Mrs. Lincoln asks the class what they think my poem could expand upon or revise for more clarity. I’m okay with taking constructive criticism—as long as I agree with it—but my stomach tenses anyway, as if in anticipation of a punch.

To this question, Will raises his hand. While I know he’s chosen to include his comments in the criticism section of the workshop, I somehow think this is maybe all a misunderstanding, that he just has to find something minuscule to criticize out of his otherwise glowing feedback lest anyone think he’s not the literary wunderkind teachers say he is. He’s going to recommend separating my block stanza into couplets for more flow, maybe. Or a title change. Some small cosmetic fix.

“I’m just not really sure what the speaker is saying in this poem,” Will begins, and like his slow pen dragging over my lines, I feel these words raze over me, too, harsh and spiky across my chest. “It’s found poetry put together in a fun way, I guess, but what is it trying to say? It feels very surface-level.”

I’m not sure what my face is doing but Gen’s jaw drops, and she jumps in first. “The message is that men on the internet are dangerous and that female journalists have a lot to put up with.”

Will shrugs. “That’s nothing new. Where’s the turn? The complication? There’s no vulnerability from the speaker here, and while I acknowledge that there’s good momentum and speed in the poem as the male commenters keep interjecting, I don’t understand the speaker’s opinion of all the back-and-forth. What’s going on between the lines here?”

I can’t look at him anymore, or at anyone else in this classroom, so I stare at my page until the words blur into a black-and-white pattern, like hieroglyphs with no obvious meaning.

“Okay,” Mrs. Lincoln says, “but we need to be more constructive here. The point of this class is to revise these workshopped poems, and I think we should delve into the specifics of why you’re confused so that Leigh can identify which parts of the poem to revise.”

“I’m not confused by any of the lines. They all make sense.” Will’s voice is slow and measured. Not angry, just flinty and pointy and frustrated. “My feedback is more overarching. When I get to the end of the poem, I don’t feel anything. It’s all style, no substance.”

And that’s the kicker. That’s the thing that coaxes the tears in my eyes to start bunching up, threatening my Maybelline Great Lash.

All style, no substance.

I want to stand up, shove my chair back, and leave the classroom, but I don’t have it in me. Because how would that look? What would the seniors or Will or Mrs. Lincoln think? Sensitive. Dramatic. Takes things too personally.

Instead, I sit there, keeping my eyes down until I can blink back the tears. The class has moved on to other points of feedback, but I hear none of it, just a lull of white noise.

Eventually I receive everyone’s comments, passed to me from both sides of the circle. Will’s are on top, and while his perfect blue cursive with absolutely no slant is lovely and legible, I can’t seem to read any of it, and I don’t want to. I put his comments at the back of the stack and shove them into my backpack while we move into the week’s reading material.

I don’t plan on reading them. I don’t want his feedback. Any semblance of a crush I had feels irreconcilably snapped. Evaporated. No evidence it was ever there at all.

All style, no substance , I hear once again in his low, sure voice.

And that’s the thing about straight, white literary men. They’re all the same at the end of the day. Even the boys who’ve barely yet learned what power they have.