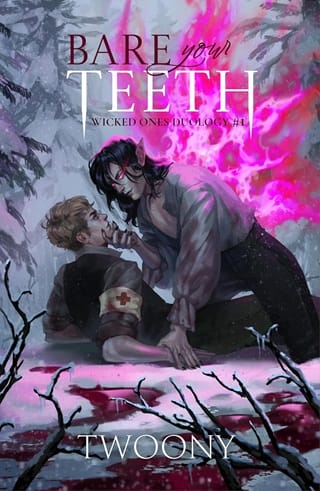

Bare Your Teeth (The Wicked Ones #1)

1. Prologue

1

W illiam Augustus Vandervult was the fourth son of Viscount Robert Vandervult, raised by luxury and love. William’s mother, Lady Matilda Vandervult, brought her boys up to be poised and fine gentlemen. Though they did not want for anything, Matilda and Robert ensured their children took nothing for granted, either.

The Vandervults were known for their charity work spread across the Heign kingdom. Orphanages and clinics mostly, so young William learned not to be disturbed by missing limbs or the sick. He found the work of doctors pure in a sense, crucial and hopeful. They possessed the Sight, a gift of magic from the Holy Soul, allowing them to tug on the strings of the world. In a flick of the wrist, doctors healed the injured, calmed the sick, or made peace for the dying.

After a hot day toiling among the clinics, Matilda often said to him, “There are many less fortunate than us, and so it is our duty to share that fortune and rid the world of a little sorrow each day.”

He thought the world of her, and his father, who shared those beliefs. His parents met in a clinic on a summer afternoon tending to children suffering Shimmer Sickness, in fact. However, the Court of Lords his father was a part of were not all known for charity. Occasionally, he eavesdropped on their conversations over the suffocating stench of cigar smoke and liquor. The court gentlemen laughed over atrocities and barked at those who dared to suggest charity.

“If we took pity on every poor bastard, there’d be more pity than gold,” Lord Hornbill loved to claim.

William found so-called gentlemen such as Lord Hornbill to be awful company and never quite understood why his father invited them over for supper.

“There will always be those among society who do not see past their own desires. Those same could rule this world if we allowed them, so occasionally we must invite them for tea and find compromise,” Robert explained to his boys, the oldest of which understood, but William did not. He found many of his father’s phrases peculiar, though that could be because he did not have the same aptitude as his brothers.

He did not know business like Arthur. He could not charm like Richard. He could not absorb knowledge like Henry. William was sensitive, so others loved to remind him. He preferred the company of flowers and animals over people. He could not stomach a hunt alongside his father or brothers. An act many gentlemen found concerning, though he couldn’t fathom why.

Matilda doted over him, though, their youngest and a spitting image of her; fair skinned, a dimpled smile, hair of spun gold and emerald eyes of promised spring.

“I would not stand another dull conversation of proud men spouting nonsense a moment longer if I had my way,” she proclaimed over an afternoon of knitting. He quite enjoyed knitting, finding the repetitive motion soothing while his brothers would have nothing of it. His mother smiled, comforting as morning sunlight. “You, my sweet child, always have interesting tales and thoughts to share. I find that far more fitting than an overly confident man who can wield a rifle or smoke a cigar.”

Matilda was the singular person who found his interest fitting. Though Robert never spoke ill of his boy, he did not expect William to follow in the footsteps of his brothers.

As the eldest and wisest, Arthur would take the title of viscount. Richard held galas across the kingdom to raise money for their charity ventures because, as Matilda once claimed, the boy could charm the britches off the king himself. At seventeen, the Holy Soul blessed Henry with the Sight. He earned a position within Heign’s Magical Society. To study magic among the most renowned mages of Heign was an honor few Vandervults had been offered before. Then there was William, the fourth son who tended to birds with broken wings and cried over books unbefitting of a boy.

“Do not let others find you reading such things,” Henry chastised after catching William huddled at the back of their house library with his nose in a romance novel. “Such books are for ladies.”

“Why?” he asked. “They are poetic and sweet. They tell of love. Can gentlemen not enjoy love?”

The bridge of Henry’s nose wrinkled. Concern trickled through his words. “Do not speak like that to others, either. They will not treat you kindly.”

“Why?”

Henry ruffled William’s hair. “Because it is not the way of things, my dear brother.”

He thought perhaps the way of things were wrong, for no one should be deprived of a marvelous book. They allowed one to explore a thousand worlds in a single lifetime. What could be more magnificent than that?

He would become increasingly grateful for the many lives spent among books, for the life he knew came to an abrupt halt at sixteen.

“He cannot go,” Matilda argued. Her voice carried through the cracked door to Robert’s office. William kneeled and dared to peek inside.

The fireplace was not lit on the mild fall afternoon and the maids had shut the windows. Dusk light glistened against the glass, revealing the warding spells marking the panes to protect against beasts and unwelcome intruders. Fae placed the wards there long before his parents were born, although his family rarely spoke of them. Many believed anything from fae would cause tragedy, but their wards and spells became necessary evils over the last few decades.

However, William found the wards eerily beautiful. They always gave off a faint glow, like dawn barely waking over the skyline, and had yet to fail in their protections. Matilda weaved stories of days before their lifetimes, where monsters didn’t roam the lands. He couldn’t imagine a world without worry, just as he couldn’t fathom how either of his parents stood the smell of the office. Robert’s guests caused the room to reek of cigar smoke and liquor. A glass cabinet containing a dozen foul tasting beverages lined the wall. He would know after Richard convinced him to taste one and he hardly made it to the open window in time to empty his stomach in the bushes outside.

Deep navy wallpaper circled the upper half of the room, designed with twisting morning glory flowers stretching to the ceiling. Ebony wainscotting completed the lower half, save for one wall where a stack of shelves contained dull books that rotted the brain.

Robert stood at a wide black desk, leaning against the same colored cane tipped in silver. His opposing foot tapped impatiently against the floor. Matilda sat on the sofa, a hand against her heart and the other pressed to her head.

William had never seen her so troubled, never witnessed such horror in her eyes.

“This is not our war,” Matilda whimpered.

“This is everyone’s war,” Robert argued and threw the crumpled letter in his hand onto the floor. “The shadowed disciples have plagued our realms for too long. Their summoned beasts are no longer rats dying in cages. We, and our children, have not known the world without their curse, without their fleshed damnations. Should this war continue, an unholy plane may spill upon ours. Calix Fearworn will cast this world in shadow, ending all life as we’ve known it.”

“Do not speak that name in our house.” Matilda pressed two fingers against her heart, as she taught William.

He begged the Broken Soul not to punish his father and prayed to the Holy Soul to forgive him for uttering a blasphemous name. The name of a murderer like the world had never seen, who would never march through the healing sea of Elysium. The Broken Soul would drag his horrors to the depths and the damned.

“Not speaking the name of evil will not defeat it,” said Robert. “Fearworn, and his shadowed disciples, cannot be ignored. The kings of Terra and the lords of Faerie agree: this is no longer a divided war. Our kings require each family to send one man of their direct lineage to the front.” Red faced and ruffled, Robert slammed his cane against the floor. “Richard and I have been deemed unfit to serve. Arthur and Henry offered themselves, but the king denied their enlistments, arguing Arthur is our heir and Henry is studying magic that our soldiers will use to survive. They’re needed here.”

“Does that not count as serving?” Matilda argued.

“No, as Henry will not see the front lines. William must go, as ordered by the king,” Robert said in the stern tone he used on the boys, the one that wasn’t as authoritative as he needed it to be. His expression was even worse, anguished and guilt-ridden.

Matilda wailed like William had never heard, sharp, bitter, and utterly broken. “He is too young. He is our baby.”

“He is sixteen.”

“William is not like our other boys. By the Holy Soul, Robert, he cannot hunt. How can any expect him to take a life? Why would His Majesty choose our William?”

“You know why,” Robert whispered.

Matilda leaned over as if that would grant her more air to breathe. Robert kneeled in front of his grieving wife. He grasped her hand so tightly William worried he’d cause harm, but Matilda returned that force. Her bottom lip trembled, so did Robert’s.

“William will do what he must to protect himself.” Robert’s voice cracked. A tear fell from the corner of his eye. “He’ll learn to survive. He’ll come home.”

That was the first time he heard his father cry. Both of his parents wept, and once he returned to his room, so did he.

William Augustus Vandervult went to war at sixteen, where he became who he needed to be to survive.