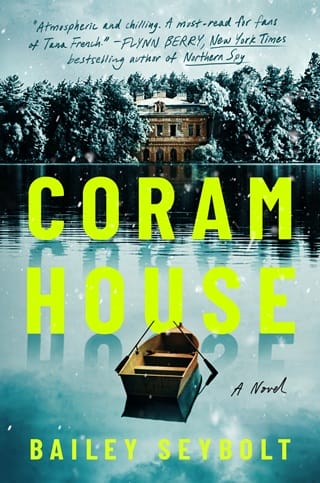

Coram House

August 1, 1968—Coram House

Sarah Dale

There’s a flock of shadows under the old oak. The one that grows at the edge of the graveyard. But no. My sun-dazzled eyes adjust. Not shadows. The sisters, their black habits hanging limp in the humid air. Sister Marguerite beckons me forward. Beads of sweat dot her hairline, soaking her wimple. It’s like she’s melting inside her robes.

“Cook is making lemonade,” she says and points up toward the House, as if I didn’t know where to go. “Bring it here, child.”

The others are playing on the beach, shouting and splashing in the cool water while Sister Ann tries to hush them. But I’m not sorry to leave. A few minutes alone are more precious than even the most perfect summer day. I take the path up the hill through the sumac, which is just starting to put out flowers. They’re still green cones—nothing like the fiery red clusters they’ll be come autumn. The air is thick with growing things. The hum of insects drowns out the sounds from the beach. In here, I’m all alone.

I arrive at the old part of the graveyard. Some headstones go back to 1800, but most of the letters are faded or filled with green moss, so you can’t tell who’s who anymore. Overgrown grass tickles the soft skin behind my knees. The dead here have no one to visit, so Marcus only cuts the grass when Father Foster makes him. Even then, he grumbles about the extra work. But I think it looks nice all covered in feathery scarlet bee balm and purple spires of anise.

I take a roundabout path that leads through the fairy circle of white pines where someone named May Sullivan has a bench just for her. She must have been loved to have such a spot all to herself. On the other side, I follow a line of identical marble squares, each bearing the name of a lieutenant or corporal who died in 1918. The grass here is cut short and the graves usually have flowers or tiny flags on them. There are still living people who care about these poor boys, as the sisters always call them. The dead boys. Not the living ones. We’re never poor boys or girls.

The path curves past a row of mausoleums that look like stone dollhouses, and there, at the top of the hill, is the iron gate leading to the House. A stone angel sits on each gatepost, her face buried in her hands. Why do they weep, I’ve always wondered, if everyone here is in a better place? Unless their tears are not for the dead at all.

Strings of spiderweb stick to my face as I step through the gate. Something crawls down my arm, but when I look there’s nothing there. Today, the yard is quiet. Everyone is down at the lake or playing in the shady woods.

The kitchen door is propped open with a stone, but it’s too dark to see inside. “Hello?” I call, but the word is all breath. The last part of the path was steep.

“Hang on,” Cook’s voice grumbles from the darkness. A dragon in her den. So I wait.

From up here, the whole of the lake shines, smooth as mirror. Way down at the other end of the beach, a rowboat bobs in the shallows. Sister Cecile stands beside it, waiting. Even from way up here I can tell it’s her by the way she stands—straight and still as a statue. Someone must be getting a swim lesson. Worse for them.

“Well, what do you want, then?” says a voice. I jump and turn around.

Cook stands in the doorway, flour up to her elbows like gloves. Hot air billows from the kitchen behind her. “Sorry, ma’am,” I say.

But she doesn’t look angry. She’s nicer than the last one.

“Sister Marguerite sent me up for lemonade?”

“Oh, she did, did she?” Cook’s mouth presses into a thin line. “Wait here,” she mutters and goes back inside.

I turn to watch Sister Cecile down on the beach. The boat bobs up and down, but she never moves.

Behind me, a crash from the kitchen. Before I can move out of the way, a boy bursts through the door, ramming his metal bucket straight into me. I go down in the dusty yard. The pain is sharp. Skin sliced from skin. My knee throbs, but once I look up into that red, freckled face, I scramble to my feet.

Fred holds his hand up to block the sun’s glare. He leans forward, so I can smell his stale breath even over the bucket of garbage. “Watch where you’re going,” he hisses.

“You’re the one who ran into me.” I try to sound hard. He’s worse if you seem afraid.

Fred picks up a stick, thick as my arm. It’s smooth and bleached white as bone. He hefts it in one hand, testing the weight. My body hurts in anticipation of the blow.

But it doesn’t come.

Fred’s eyes catch on something behind me. Then he’s pushing past, knocking me to one side like I no longer exist. I watch as he disappears down the path to the lake, his white shirt blinking in and out of view among the green branches. I count to one hundred to make sure he’s gone. Blood runs from my knee and soaks my white sock.

“Should I just stand here all day, then?”

I turn back to see Cook framed in the doorway, holding a white ceramic pitcher. Beads of water cling to the outside.

“Sorry,” I mutter and fumble to wipe the dust from my hands.

“Oh, drat. Hold on. They’ll want glasses.”

The dark kitchen swallows her again. This time, I stand at attention, waiting for her to reappear. It takes forever. The blood on my leg dries to a crust. She returns with four empty jars.

“Had to wash them up. Here, take them.”

She thrusts the stack into my arms. But I don’t understand.

“Where are the others?” I ask.

Cook’s eyebrows knit together. “The others?”

“The glasses,” I say. Are we all supposed to share?

But she misunderstands. “If Sister Marguerite expects me to send real glasses to the beach where they’ll be smashed to bits, she can come get them herself.”

Then she grumbles off into the kitchen.

Of course. Four glasses, four sisters. How stupid to think that the lemonade would be for us. I turn to go, already deciding to go back the long way. I’d rather walk an extra mile than run into Fred alone on the path.

The rowboat is out on the water now, floating right in the middle of the cove.

Sister Cecile sits in the stern and a boy sits in the bow, tall and lanky, his white shirt glowing in the sun. That’s where Fred was going in such a hurry, then. The pitcher is slick in my hands. I try to get a better grip. Down on the water, the rowboat spins, blown by the breeze. Now I can see another boy, small and huddled, but I’m too far away to make out his face. Sister Cecile casts her arm toward the water, as if throwing a stone. In answer, Fred lunges forward. In a blur, the smaller boy goes over the side. His arms and legs thrash the water to foam. Time stretches forever.

A swim lesson. A swim lesson. The words repeat in my head like a prayer.

The frothing water stills to ripples, then goes smooth.

No small head breaks the surface.

I don’t move. I can’t move. The others in the boat are frozen too. Sister Cecile, a black triangle. Fred, a smudge of white shirt. Only two now. Time stretches forever. Then Fred lifts the oars and begins to row.

Cold needles sting my leg. I look down. They’re wet. Shards litter the ground. I must have dropped the pitcher, but I never heard a smash.

When I look up again, Sister Cecile is watching me from the boat, which is almost back to shore. She can’t possibly see my face from all the way down there, but I still want to hide. She’ll send me back to the attic. I know she will.

A sound escapes my lips and I hold a hand to my mouth, stuffing it back in. The pieces of the pitcher lay in the dirt, jagged and white. I feel as if they might leap up and put themselves back together. As if I can turn back time and do things differently. As if I can know what’s coming and hold on tighter.