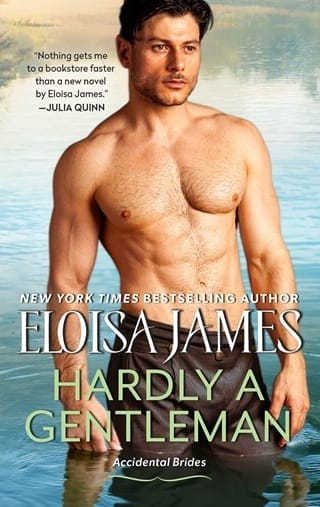

Hardly a Gentleman (Accidental Brides #2)

Chapter 1

April 10, 1803

Scotland

Caelan Eneas MacCrae, Laird of CaerLaven, was up to his thighs in freezing water, his bollocks flinching with every splash.

Spring was finally fighting off winter: the heather was turning purple, and he had a hatful of wild garlic sprouts waiting for the two trout he’d already caught.

Aware of a dim feeling—icy bawbag or no—that life didn’t get much better, he flipped his long rod forward and let the silk spin out, his fly splashing down with a sound better than bagpipes or trumpets.

His sister’s voice interrupted the delicate process of snapping his rod just enough to set his fly bobbing. “You’ll catch your death, standing in that loch like a naked gowk.”

Caelan bit back a curse, turning his head to find Fiona on the bank in a muddy dress, hair blown out around her face like red clover. She must have walked across the two fields separating his estate from that of his brother-in-law, Rory McIntyre.

“Turn around if you dinnae want to see me in the altogether,”

he said by way of greeting, beginning to reel in his line. Fiona wouldn’t pay him a visit unless she wanted something, and she wouldn’t leave until they’d argued it out. He was stubborn, but his sister was twice as obstinate.

She threw a dramatic hand over her eyes. “What would Mother say?”

Mother would have ranted. The poor woman had waged a relentless, failing campaign to civilize her family.

“She’d be calling on the world, the flesh, and the devil,”

Fiona said, answering herself. “All of them in one package, when the laird himself is naked in the out-of-doors, teasing local lasses with his muscled thighs and burly chest, with nary a fig leaf covering the family jewels.”

“There’s naught but my crofters between here and the village,”

Caelan said, tossing his rod onto the bank. “They have more to do than gawp at me.”

“My better half wants one of those newfangled twirly things,”

Fiona said, pointing to Caelan’s reel. “I suppose I might get him one for his birthday, except I wouldn’t want the maids admiring Rory’s naked arse in a stream.”

“As I said, there’s no one to see. I have only Mrs. Baldy, and she—”

“I regret to tell you that I had a dispute with that woman over rotten mutton, and she’s left in a huff.”

“Bloody hell.”

He plucked his kilt from a bush, buckled it on, and turned to pull his creel out of the stream. “She’s the first housekeeper who stayed more than a few weeks.”

“I threw the mutton over the wall,”

Fiona said, “thereby saving you from a nasty death by dysentery. According to her, she’s been feeding you porridge—”

“Nothing wrong with that.”

“Porridge, cabbage soup, pigs’ thinkers—which she clarified as brains—and mutton stew.”

“Sounds right,”

Caelan said, going down on his haunches next to the flat boulder he used for cleaning fish. “I cook trout myself, and otherwise I don’t care much what I eat.”

A fact his sister knew perfectly well.

“How’s the Bean?”

“You have to stop calling him that. Alfie is seven years old and tall for his age.”

Fiona squatted down beside him, pulling a knife from her skirts and slicing open a trout while he started on the other.

“And?”

“He’s a pain in the arse,”

she said darkly.

“He seemed fine at the kirk last Sunday.”

“He’s obsessed by his pet chicken, Wilhelmina. He says that he can tell from her expression that laying an egg is hideously painful, ‘like passing a shite the size of a boulder.’”

Caelan’s bellow of laughter echoed over the water.

“Aye, you can guffaw,”

Fiona said. “You don’t have a son who refuses to eat chickens or eggs.”

“What kind of chicken is Wilhelmina?”

Caelan asked, still grinning.

“A silkie, so called: a chicken with a mop of white feathers on top of its head. A grifter at the market rooked Alfie into believing she is half rabbit, half chicken.”

Caelan groaned. “That’s so wrong.”

“Rory offered to turn her into rabbit-chicken stew, which resulted in tears and screaming accusations of cruelty, capped by Alfie being sent to bed with bread and milk for supper.”

“Happened to you many a time without stunting your growth.”

“And to you,”

his sister retorted. “I do understand the appeal of the carnivorous wilderness, Caelan. But—and I mean this—would it emasculate you to live in a sanitary dwelling? With a pantry that had more than a few withered carrots and some flyblown mutton?”

“There’s a partridge hanging off a hook in the courtyard,”

Caelan objected. “And these fine trout. What more do I need?” He meant that sincerely. The castle was merely a place to live and food just something to eat.

“A housekeeper, a cook, two housemaids, and a scullery maid,”

his sister said, flipping gills into the heather.

He hated fuss and noise, which servants brought along with them. “Mrs. Baldy was no bother. She made a cup of tea when I shouted for one and didn’t mind serving me outside.”

“Aye, but she’s gone, remember?”

“I’ll have to hire another housekeeper,”

Caelan said, resigned. “And a maid or two.”

“You’ll have to start wearing a shirt. Decent women aren’t used to seeing brawny chests. A pair of smalls under your kilt, as well.”

“I don’t see any reason to stain a shirt with fish guts if I can avoid it.”

Fiona sighed. “You can’t live like this.”

“All signs are that I can.”

“The castle is filthy.”

“That’s an exaggeration,”

he said, wondering if it was. He didn’t tend to notice dirt.

“Your study is littered with books, fifteen dirty teacups, piles of horsehair, and drifts of foolscap around your desk. I assume from the horsehair that you’re still writing a guide to fly-fishing?”

“That, and a book about Scottish whisky.”

“I dinnae know how you survive without an estate manager. Father was besieged by crofters on open days.”

Their father had refused to make repairs of any kind and had spent open days brawling with his tenants. Caelan considered himself lucky to have escaped his father’s red hair and temper, along with his tightfistedness. The former laird would have exploded with rage if he knew about the money his heir had sunk into improvements.

The upshot was that CaerLaven crofters could support themselves and their children, not merely by farming but also by brewing small batch whisky. “I don’t find the crofters unreasonable.”

Fiona tossed two fillets into the creel, rinsed her hands in the stream, and carefully wiped her knife on the moss.

“Lunch?”

Caelan suggested.

“I’d be taking my life in my hands eating anything from that kitchen.”

“I do my cooking on the courtyard hearth. Look, I found wild garlic.”

“All right,”

Fiona said, shaking out the skirts of her riding habit. “I can’t believe you’re using that fireplace. I remember Mother refusing to allow the cook to go near it on the grounds that we were no longer living in the dark ages.”

“It works,”

Caelan said, leaving it at that. “Why are you paying me a visit, Fiona? The Bean’s not the first nor the last laddie to be obsessed by shite.”

“I mean to talk to you seriously about your future,”

his sister declared.

“Ah, bloody hell,”

he muttered, picking up the creel and his rod. Sure enough, she lectured him about the benefits of marriage all the way back to the castle, not even stopping when they got home.

“There’s a good example of what I mean,”

she said, pointing at some large stones lying under the south tower.

Castle CaerLaven was one of the smallest castles in the country, but it was one of the oldest as well. To Caelan’s mind, it had everything a castle should have: two towers linked by a stone rectangle set at right angles, and an interior courtyard with room to house fifty crofters if the MacCraes were ever besieged.

Which they never were, being as his ancestors had been quick with a claymore and more than capable of fending off aggressive clans and stray Englishmen who thought to steal CaerLaven land.

“What do the rocks have to do with this wife you’re proposing?”

“CaerLaven is going to rack and ruin,”

Fiona declared, crossing her arms over her chest. “You’re letting our ancient holding decay inside and out.”

“I am not,”

he said, stung. “Those stones were left over from repairing the battlements in the north tower, and they’ll be used for the south in the summer. I’ve had the stonework repointed and most of the beams replaced. Remember how the nursery ceiling was always sifting wood rot?”

“The nursery won’t be the same without that frightful creaking during windstorms,”

Fiona said nostalgically. “I always pretended that I was sailing the seven seas, not realizing I was in mortal danger.”

“Mortal danger is an exaggeration. Magnus got up in both towers and tapped the beams. The termites haven’t weakened the structure.”

Fiona rolled her eyes; their mother’s injunctions against graceless gestures never caught on with her. “The castle is decaying inside, if not outside. There’s a foul, boggin smell in the kitchen. I swear our chicken coop is in better shape.”

“You already made your point about a housekeeper.”

“Yes, but a wife keeps a housekeeper. You rattle around like a pea in a pod, not even noticing your surroundings. I worry for your sanity.”

Caelan pushed open the front door, refusing to dignify that foolishness with an answer. Fretting over nonsense like a smell in the kitchen was a waste of time.

“And your body as well,”

his sister continued, walking into the castle before him. “Eating little more than porridge and pigs’ thinkers. Did’ya never wonder what happened to the rest of the pig—which you undoubtedly paid for?”

He frowned.

“Mrs. Baldy was selling some lovely bacon out the back door, I’ve no doubt,”

Fiona declared. “I know you hate fussing, but bow to the inevitable, Caelan: I’ve decided you need a wife. What kind of lass would you consider? I’m not talking about the women down at the tavern.”

“I will not marry again,”

he said, as firmly as possible.

Fiona turned and put a hand on his cheek. “Caelan, dearest. I ken you fear losing another wife, but that’s no reason not to live.”

Fire burned under the surface of his skin because he hated it when people talked about Isla.

His sister rattled on. “Don’t I know how much you loved Isla? But it’s going on two years. You’re twenty-seven next month, and the time has come to move on.”

Jesus. She had no intention of giving up.

“You need an heir,”

she announced, “and for that you need a wife.”

She was like a damned dog with a bone. Aggravation curled in Caelan’s gut as he lit a fire in the old stone hearth and threw the trout on the rack. “I have an heir. The Bean.”

“Alfie is Rory’s heir, not yours. Remember how he got that name? The Bean was born far too early, and it’s been seven years since he was conceived. I’m thinking the chance of me producing a spare for you is slim.”

“I don’t give a damn about having my own heir. Our lands adjoin, which would make Alfie the only laird in these parts to brew two different whiskies.”

“Sometimes I see that square chin of yours, and I feel as if Father has risen from the grave. You got the best of him otherwise,”

Fiona said. “You got his jawline, thick hair, and those gray-blue eyes.”

Thankfully, the trout were cooked to crispy perfection. He dropped them onto a bed of wild garlic. Mrs. Baldy had left a stack of tin plates and some forks on the hearth.

They ate outside at a stone table that had reportedly been used by their ancestors to gut their enemies. More prosaically, in the last two years, he’d got in the habit of eating there unless it was raining or snowing.

“I’ve no plans to marry again,”

he stated.

“You have to—”

“I do not have to do anything I damn well don’t want to do. And I don’t want another woman. Ever.”

Fiona looked so shaken that Caelan tried to lighten the mood. “No lady knows how to clean a fish the way you do.”

Fiona wrinkled her nose. “Me? I never would have caught a man if Rory hadn’t been right next door, bent on seducing me in the barn.”

“I don’t need to know that!”

Fiona laughed with the confidence of a woman whose husband had fallen in love with her at the age of fourteen. “My point is that I’m rawboned and better suited to being a lumberjack than dancing a quadrille.”

“What’s a quadrille?”

“A new dance that’s all the rage in Edinburgh. Thank God the Bean isn’t a girl. I despair to think what a mess I’d make rearing up a young lady.”

She put down her fork, her eyes softening. “I know how you’re feeling, Caelan. You may never fall in love again, not after Isla. She was lovely as a rose in June. The world knows you were desperately in love with her, but it’s been two years.”

He took a bite of trout. “Aye.”

His sister’s smile wobbled. “I’ll never forget when the two of you left the kirk together. The sun came out from behind a cloud, and apple blossoms blew across the churchyard as if the world itself was celebrating how lovely the two of you were together.”

He stood up, picking up his plate and Fiona’s.

“I can’t help worrying about you,”

she burst out. “Living alone, turning into a curmudgeonly widower with no one to share your kitchen or your bed.”

Caelan turned around and scowled. “I’m happy as I am, Fiona. Leave it be.”