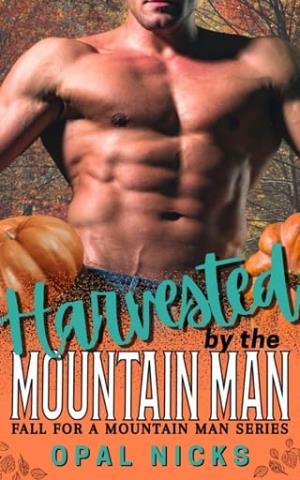

Harvested By The Mountain Man (Fall For A Mountain Man #3)

Chapter 1

Hannah

“J ust one more page, mommy,” Ivy says. I’m holding a book that has exactly thirty-two pages, and we have already negotiated for the last four.

“Two,” I say, because I’m a pushover for good-night bargains and I like the way her eyes light when she wins things she didn’t expect to win.

We’re reading Cinderella. I’d tried to steer her toward the hedgehog one, the story where the prickly creature saves a village with his cleverness, but there were pumpkins on this cover and that was the end of that argument.

I start the next page, balancing the book on my knees and lowering my voice for the fairy godmother. Ivy presses her palm to the page like she can absorb the story better that way. She’s admiring the new gown the fairy godmother has created out of thin air.

“Do you think the dress itches?” she asks.

“Probably,” I say. “Anything that sparkly has to be itchy.”

“What about the shoes?”

“Those are definitely delicate being made of glass,” I say. “And slippery.”

She considers this as I watch her mind absorbing the tale. “If I had a fairy godmother,” she says, matter-of-fact, “I’d ask for the kind of shoes that don’t hurt. And a pony that knows how to count.”

“Those are good requests,” I say. “Very practical. Your godmother would be proud.”

We keep going. I read the part about magic transforming mice into coachmen and a pumpkin into a carriage.

Ivy makes a small surprised sound every time the picture changes.

I have the words memorized, but tonight they sit in my mouth like a truth I don’t know how to tell.

Happy endings are a page turn away in books like this.

In real life, sometimes the clock strikes midnight before you ever get to the dance.

Ivy points at the prince. “Does he really love her? He doesn’t know her very well.”

“That’s a very smart question,” I say, stalling for time. “Maybe he loves how he feels when he’s with her. Sometimes you know people fast.”

“Like when I met Miss Carla at school and I just knew I wanted her to be my teacher forever?”

“Like that,” I say, because that answer is kinder than the ones I hold close. People can love you fast, and they can leave you fast too. The mind is a funny thing. It holds the memory of a slammed door longer than the sound the door made.

We reach the last page. Ivy sighs with satisfaction at the twirling gown, the glowing castle, the happily-ever-after stamped in a cursive font like a promise.

I close the book and wedge it onto the crowded shelf.

There are crayons in the gap where it used to reside, along with a plastic bracelet and a sock that has been missing its partner for two laundry cycles.

Life here has edges, yes, but it’s mostly soft. It’s mostly ours.

“Can we go get pumpkins tomorrow? I want two – a big one and a small one … just like you and me” Ivy asks.

She says tomorrow the way other people say Christmas. I tuck the quilt around her shoulders and smooth the hair from her forehead. “We can do that,” I say. “We’ll go to the ranch out in the valley. They have hayrides and hot cider.”

“And goats?”

“Yes,” I chuckle. “Very hungry goats.”

She giggles, satisfied. “Okay. Goodnight, Mommy.”

“Goodnight, Goose.” I kiss the warm spot above her eyebrow and switch on the small moon-shaped nightlight. Stars scatter across the ceiling in a faint spray of plastic glow. I stand in the doorway for a minute, listening to her breath settle into a slower pattern.

In the kitchen, the sink is full of dinner dishes.

The counters are clean in the way you clean when you’re tired.

They’re wiped but maybe not completely clean.

I load the dishwasher and stare through the window over the sink.

The sky outside is the color of blackberry jam.

Somewhere in the distance, a dog barks. Somewhere closer, a car door closes hard and a porch light clicks on.

It’s a neighborhood soundtrack I’ve grown used to, an ordinary chorus of people living their life, doing their best.

My phone vibrates on the counter. Marcy’s name brightens the screen with a confetti of text bubbles before I can even unlock it.

MARCY: How’d bedtime go? Did the princess get the prince or did our girl unionize and demand fair wages for pumpkin mice?

I smile and hit call.

“Hey,” she says, picking up on the first ring. “Tell me you survived Cinderella.”

“Barely,” I say. “I made it itchy. The dress, the shoes, the whole situation.”

“Good. Someone has to add grit to the narrative.” I can hear clattering in the background on her end, the cheerful chaos of three boys and a Labrador. “So what’s your beef tonight, Mama Bear?”

I lean my hip against the counter and watch the porch light next door blink off. “I keep wondering if I’m doing her a disservice. Filling her head with magic. Setting her up for disappointment.”

“You mean stories?”

“I mean happy endings.”

Marcy’s pause is short and not unkind. “You wanted happy endings once too.”

“I also wanted a partner,” I say quietly. The words scrape on the way out. “Someone who shows up when the sink clogs and the car won’t start and the kid is home with a fever and you haven’t had a proper haircut in eight months.”

“Do you want me to remind you of the many, many ways in which the sperm donor failed the partner test?”

“No,” I say, a laugh catching me by surprise. “I was there.”

“Right,” she says. “So maybe the lesson isn’t not believing in magic. Maybe it’s being choosy about the magician.”

I open the fridge and stare at the shelf where the milk should be. “We’re out of milk again.”

“Which is why you’re going to the ranch tomorrow,” she says, undeterred. “Maybe they’ll have milk there.”

“They have a little market,” I say. “I promised her pumpkins.”

“Ivy deserves pumpkins the size of small planets,” Marcy says. “And you deserve to let yourself have a nice day that doesn’t feel like a test. That’s not illegal, you know.”

I sit at the small kitchen table and trace a finger over the nick where Ivy banged a spoon into the wood while we made pancakes last Sunday. “Sometimes the stories make her ask questions I can’t answer.”

“Like?”

“Like does the prince love her forever. Will he help with dishes.” I rub my forehead. “She doesn’t use those words, but that’s what I hear.”

“And you’re worried that if you say yes, you’re lying. If you say no, you’re stealing something.”

“Exactly.”

Marcy sighs in that way she has that sounds both wise and tired.

“You don’t have to answer the future. You can answer the moment.

You can say real love looks like showing up.

Some people don’t. Some do. And then you show her the ones who do.

The librarian who stayed late so the kids could finish their pumpkin crafts.

Mr. Jenkins who fixed your leaky faucet because he was a genuine nice neighbor.

The world is not short on magic. It’s just not always wearing a ball gown. ”

“You’re irritating when you’re right.”

“Then it’s a good thing I’m nearly always right.

” A crash on her end, then muffled voices.

“Okay, I have to go stop my middle child from inventing fire. But promise me you’ll take pictures tomorrow.

And have the hot cider. And for the love of all things autumn, do not buy the pre-carved pumpkin with glitter eyebrows again. ”

“That was one time,” I protest. “And Ivy loved it.”

“Because it had glitter eyebrows,” she says. “Go to bed at a reasonable hour. Tomorrow is for fun and making memories.”

“Goodnight, Marcy.”

“Night, Han.”

The call clicks off. I put the dishes in the dishwasher and start it, the hum filling the quiet like a cat purring.

I set out Ivy’s sneakers by the door and her favorite yellow sweater.

I fish my own sweater from the back of a chair and shake out a crumpled grocery receipt from the sleeve.

There’s a peace in these small preparations, like I’m laying down breadcrumbs to lead us somewhere better.

In the bathroom, I wash my face and catch my reflection in the foggy mirror.

The woman looking back at me could pass for pretty if pretty had dark circles and a ponytail that gives up its fight by noon.

I pat moisturizer into my skin and think about the way Ivy’s hand felt in mine when we crossed the street this afternoon.

It’s so small. It trusts so completely. I can carry that trust. I can be the place it lands.

On the way to bed, I pause by Ivy’s door.

She has kicked the quilt into a mountain between her knees and the headboard and is sprawled like a starfish in a puddle of silver light from the window.

Her stuffed rabbit, Queen Lettuce, is wedged under her arm.

I tiptoe in and ease the blanket back over her, tucking it under the curve of her shoulder. She sighs and burrows down.

Back in my room, I crack the window. Cool air slips in, carrying the faint scent of woodsmoke.

Even from here, in this rental with the thin walls, I can feel autumn gathering itself.

Kids will be bringing home construction-paper bats any day now.

The coffee shop has already offered fall favorites.

The grocery store will shove canned cranberry sauce onto an endcap and pretend we’re ready for all of it.

I climb into bed and pull the covers to my chin.

The book on my nightstand is not a fairytale.

It’s a collection of photographs and poems about urban gardens and the way plants find cracks to grow in.

I don’t open it. My eyes are heavy. But I silently wonder how something grows wild …

beginning in the dark, only to make its appearance in unpredictable places.

“Maybe magic still exists,” I whisper into the dark.