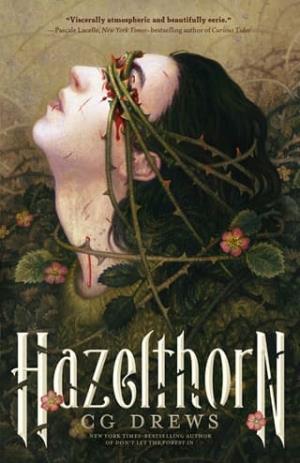

Hazelthorn

Chapter One

ONE

He knows what it is to be buried alive, the feeling of dirt in his mouth and the quiet fitting around him like a well-tailored grave.

Sometimes Evander still tastes it under his tongue, that rich earth clotting between his molars.

He should have grown out of the memory by now, but he belongs to it, and not in a gentle way.

Sometimes he feels like he’s still outside, moldered down to the bone with roots woven through the soft tissue of his lungs and rot spilling from the remnants of his rib cage.

No one saved him in time. He was never dug back up.

Maybe all that’s truly left of him are white bones in the garden, and his ghost is the thing now rattling around the hollow expanse of this bedroom in the ancient, moth-eaten manor of Hazelthorn.

Except ghosts don’t develop blood blisters along their arms after being viciously pinched, and Evander has just given himself his fourth welt of the evening. A little shock of pain for proof of life.

The grim sky has brought on an early twilight, and the gloom has put his mood through the floor.

It gets to him, sometimes, how lonely he is.

Only the elderly butler flits in and out of his room every day, bringing doses of thick, milky medicine that makes Evander feel sluggish and dulled.

He’ll flop onto his bed and stare at the wallpaper until the pattern of dead-eyed fauns and bloody thorns stops spinning and the loneliness passes.

Then he wakes.

And it begins again.

the same and the same and the same

He gave up screaming a long time ago.

All that’s left is to let the quiet thicken about him like a shroud as it runs a tongue around the rim of his ear, forcing him to listen to every noise he hates drifting in from the cracked-open window.

The hushed whispers of trees, the trill of night birds and cicadas as they flitter between the many walled gardens, the humid breeze riffling the laurel hedgerows.

The smell of summer is relentless, an unfettered punch of evergreens and florals, overturned soil and tree sap and life life life.

He could slam the window shut, but then the garden wins. Seventeen years old and afraid of the outdoors? Pathetic.

But it’s just that when he looks at the garden he thinks of blood.

He thinks of the shovel coming down.

He thinks of dirt hitting his face.

He thinks of the “accident,” as his guardian calls it.

it was an attack and you know it

His position in the oriel window seat isn’t exactly helping his spiral.

He’s in a slouched U-shape with a book one inch from his nose, his legs halfway up the engraved scrollwork and his neck at a crooked angle against the velvet upholstery.

The cushions are over a hundred years old, the emerald dulled to a decayed black that matches everything else in his musty room.

It’s all rotting, the Hazelthorn Estate.

And he’s rotting along inside it.

From his second-story vantage point, he has a fair view over the dense expanse of the gardens—the old stone walls and massive trees and hedges gone rogue as thorny vines steal over everything with writhing malevolence.

The word overgrown doesn’t do it justice.

The gardens are unmatched, unmanageable, terrible in their wildness.

Even the cobbled path around the house is half-vanished, gnarly weeds sprung up between the stones and brambles clawing up the manor’s ivy-choked walls.

Sometimes Evander will sit in this window seat and watch Mr. Byron Lennox-Hall himself stomp out there with hedging shears, still wearing his creased dress pants and waistcoat, his shined oxfords soon flecked with grass clippings.

He doesn’t hire gardeners or any kind of staff aside from Carrington, choosing to manage the grounds himself with irregular, though brutal, efficiency: snapping green throats, pruning vine arteries, glowering the shrubbery into submission.

He’s an austere man, quiet and stern. But if he’s outside, he always glances at Evander’s window and raises a hand to say hello.

It’s what a father would do.

Not that Evander would know; he doesn’t remember his parents’ faces.

Mr. Lennox-Hall has been his guardian since he was ten years old, though he’s often on business trips for interminable stretches.

When he returns, he’ll visit Evander for a game of chess, a brief pat on the shoulder, and a promise of new books.

Maybe he’s this brusque with his real grandson, but Evander wouldn’t know.

He isn’t meant to think about that boy, but still likes to put the wretched name in his mouth and roll it around like bitter hard candy.

“Laurence Lennox-Hall,” he whispers to the garden. “Laurie.” And, because his throat feels rusty from disuse, he adds, “I hate him.”

There is a morsel of heat to it, just enough to scald the underside of his tongue and make him think of how it would feel to etch that name on the window glass with his teeth.

He doesn’t remember what it was like before, when the two of them were children, the best of friends just as their parents were, living out of each other’s pockets while their laughs echoed between the garden walls.

But it’s common to forget things after almost dying.

An unmistakable thunk sounds from the heavy oaken door to his bedroom.

Key in lock. Evander sighs and lets his legs slide bonelessly down the wall before he pushes upright.

Eight p.m. sharp. Time for meds and then he’ll watch a documentary on his ancient laptop until he falls asleep.

Hazelthorn has barely dragged its decayed corpse into the twenty-first century, and installing internet was apparently a step too far.

But he has recordings. He has books. He’s safe here.

They’ve put him in the partially closed-up north wing.

His room is neat and comfortable with a behemoth four-poster bed surrounded by dark velvet drapes and wallpaper imprinted with poison oaks and moths and feral little fauns.

There’s no fireplace, though he always wishes for one when winter grows bitter.

Bookshelves line the walls, a writing desk is tucked into the corner, puzzle and logic games are stacked in piles, and there’s a worn track in the carpet from the window to the door thanks to his pacing.

The blood in the carpet is imperceptible now. He hardly ever thinks about it.

He waits for Carrington to bustle in with his meds, but the door doesn’t open.

Evander frowns. He heard the lock turn—didn’t he?

Careful, as if this is a forbidden act, he edges across the room and presses himself against the hard oak of the door. His fingertips rest lightly on the brass knob.

He starts to twist it, slowly.

The knob gives with an old groan. The door swings open.

Beyond it, the inky dark of the hallway stretches like a diseased throat, no butler in sight.

Someone unlocked his door and then left.

Confusion pools in his gut, liquid anxiety that has him tapping his fingers against his thigh as he peers into the hall. The last time he left his room was—

He can’t remember.

The door is locked for a purpose, for his safety.

He didn’t understand it as a child—newly ill and orphaned and traumatized—but now the boxed-in perimeters make sense.

If he has an episode there is the safety of his bed, the restriction of these walls, the familiarity of everything in its place. To leave is unthinkable.

He lingers in the mouth of the doorway, anticipation raising gooseflesh along his arms.

“Carrington?” It comes out thin, echoing down the long hallway like a plaintive child. He coughs, deepens his voice, tries again. “Um, Carrington?”

The dark stares back, mouth wet.

He steps into the hallway, not quite breathing, no idea where he pulled this daring from.

His bare toes curl on the worn carpet, his hand running lightly along the wall for balance since no lights have been turned on.

Gilded-framed art lines the dark wallpaper and every door is shut.

He tests a few knobs out of curiosity. Locked.

No one uses the north wing except him, and the quiet is so dense that he never hears a single sign of life from anywhere else in the mansion.

The rabbit warren of twisting halls leads to a steep, narrow staircase that curls down to an odd landing, and he crouches to peer through the banister railings to the floor below. His legs feel ridiculously coltish, his chest full of hummingbird wings.

Faint voices drift up the staircase, muted and indistinguishable.

There are people in Hazelthorn.

Evander can’t breathe. His stomach is full of curdled cream and rotted violet stems and he can’t wrap his mind around the wrongness of this.

Aside from Carrington and himself, no one else is allowed onto the estate—the sole exception being Mr. Lennox-Hall’s grandson, but even he’s only permitted when school is out and his grandfather is home.

Which he isn’t. Mr. Lennox-Hall is still on his latest business trip.

That is the ironclad rule: Evander and Laurie can never again be left alone together.

Evander must have lost his goddamn mind, but he slips downstairs, his bare feet silent on the carpet. Go back to your room, something inside him hisses, but he can’t stop himself.

He blinks to adjust to the moody light flickering from chandeliers that line the hallways as he passes an ornate dining room and stuffy library, everything drenched in shadowy shades of deep green. The voices, the music, have sunk hooks in his throat and he is helpless as he is drawn in.

“… happens when you get yourself expelled.”

“I was not expelled, Carrington.”

“—your grandfather won’t take this kindly.”

“Since when does he ever take anything about me kindly? I hate the old bastard. Long may he rot.”

“That’s enough—”