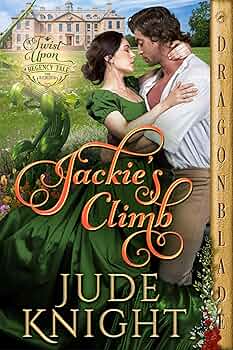

Jackie’s Climb (A Twist Upon a Regency Tale #9)

Chapter One

Tissingham, a small village in the Midlands, 1820

J ackie was late, and he was going to be in trouble. She was, rather. At her morning job, everyone thought she was a boy, but in the afternoons, Jackie went back to being a girl. A girl who sat inside on a glorious day like today and sewed, dammit. To be sure, since it was fine, Madame might permit her to sit in the little garden at the back of the cottage, with sheets spread out on the ground and over the garden seat to protect the precious gowns she and Madame were making.

Or shirts. Jackie was currently sewing two dozen white shirts for the viscount. Horrid man, and horrid shirts. Shirts were so boring.

That was not why she was late. One of the squire’s horses had come up lame. Jackie had applied a poultice first thing this morning and needed to change it for another before she came home. But someone—Dan Whitley, she was prepared to bet—had hidden the epsom salts, and no one could tell her where they were. She eventually found the jar tucked into the feed trough in one of the empty stalls. By the time she’d made the poultice and applied it she should have been home already.

Dan Whitley was a problem. Ever since he’d been threatened with dismissal for tripping Jackie up, he’d been out to make Jackie’s life harder. Of course, he’d thought Jackie was a boy and didn’t know why Tom Harris, the stable master, made a fuss about a little bit of rough housing.

For the moment, the bigger problem was Madame La Blanc, the dressmaker, who had expected Jackie home thirty minutes ago. And Jackie still had to change from trousers into skirts without anyone seeing her!

Some days, even Jackie was confused about who she was. In the little cottage just outside of the village where she lived with her mother, she had two identities. During the afternoon, she was Miss Haricot, the dressmaker’s apprentice. But when the customers had all gone home and Madame La Blanc had shut all the curtains and locked the doors, she was Mademoiselle Jacqueline de Haricot du Charmont, and Madame was Madame la Comtesse de Haricot du Charmont and her Maman.

Maman spent the evenings in the thankless task of transforming Jackie into a lady fit to be presented at court. In Maman’s daydreams, someone would one day appear at the door of their cottage with the fortune that Maman and Papa had left behind in France twenty-six years ago, one step ahead of Madame Guillotine.

“And then we shall leave this village and brush its dust from our shoes. We shall go to Paris, and you shall be presented at court, Jacqueline, ma cherie , where I fancy the name of de Haricot du Charmont will still command some respect. You shall make a grand marriage, Jacqueline.”

Jackie had no desire to live in France. She had been born in England and had spent her entire life here. And she did not want to be a seamstress or a lady of the court. As for a grand marriage, she would not know what to do with such a thing. She much preferred her morning job, as a stable boy in the stables of Squire Pershing, but if she could have anything she wanted, she would have a home of her own from which no grasping landlord could eject her, a husband who cherished her, and children to love.

At Squire Pershing’s place, she was Jackie Bean. Nobody except Squire Pershing and Mr. Harris knew that Jackie was a girl. They both went along with the ruse because she was useful.

“Young Jackie has the best hands with a horse of anybody, man or woman, I’ve ever seen,” Mr. Harris said to Squire Pershing eight years ago when Jackie was fourteen, after she’d managed to deliver a foal that both men had given up on. And Squire Pershing replied, “You can keep him then, as long as no one finds out that he is a she.”

The Pershing stables would do, since she loved working with animals. For the dream of home, husband, and family was just about as likely as her mother’s triumphant return to the French court. The village men avoided her as too educated, and the upper-class men had only one use for a seamstress, and it did not involve marriage. Well, too. They were not, after all, going to sew their own shirts.

Jackie also had a fourth identity. A year ago, she had begun to go out at night, disguised as a young man. Not every night. Once a month. More recently, once a week.

Jack Le Gume played the games of chance that Jackie’s father had taught her. The games of chance with which her father had supported them and ruined them. But the rheumatics had seized Maman’s fingers so she could no longer sew for hours at a stretch, and what Jackie could earn at the stables did not make up for Maman’s diminished income.

Jackie was careful. Unlike her charming, irresponsible, impossible father, she never gambled with money she did not have. When the luck went against her, she left when she was empty-handed. When the luck smiled on her, she left when she was still winning. She won more often than she lost, and she had managed for the past few quarters to pay the rent, even to save a bit to pay for a doctor.

Rent day was coming round again, and the rent jar held nearly enough money. If the viscountess once again withheld the money she owed Maman, Jackie would put in the pound that Jack La Gume used for stake money. One way or another, they would meet the rent, thank goodness. The viscountess would not hesitate to turn them out of their cottage, and her son the viscount—Jackie shuddered. What Viscount Riese wanted from Jackie he would never have. She would kill herself first.

No. If it came to that, she would kill the viscount.

Even as she had the thought, she came within sight of the cottage and stopped. She recognized the curricle standing outside, the high-bred pair in the traces shifting impatiently as they waited under the groom’s firm hand. Viscount Riese was just entering the cottage. Surely, he had not called for his shirts? They would be delivered to him at the end of the week, as Maman had promised.

Whatever his errand, Jackie did not want to see him. She went back around the corner out of sight, climbed over a stile into the field where they kept their cow and ran alongside the hedgerow, keeping low enough not to be seen over the top.

At the far end of the field, another stile allowed access to the Haricot’s back garden. Jackie made her way to the back door and let herself into the workroom, being careful to make no noise. She could hear voices from the front room. Maman and Viscount Riese.

“Double the rent?” Maman was saying. “But that is not what was agreed, Monsieur.”

“You were told at the last quarter.” That was Lord Riese, sounding bored. “Five pounds. On Lady Day. Or you will be evicted.”

“ Impossible! ” Maman exclaimed, giving the word its French pronunciation. Maman always reverted to French when she was upset. “ Non . That is not what was agreed.”

“You are not, I hope, calling me a liar, Madame La Blanc.” Riese’s tone had changed to low and dangerous.

“ Comment allons-nous payer ?” Maman’s low mutter was to herself, but Riese answered.

“How are you to pay? Do you know what, Madame? I have an idea. You have something I want, and I am prepared to pay to get it.” Now he sounded amused.

“ Monsieur , I think it is time for you to leave,” Maman said. She had guessed what the viscount had in mind, as had Jackie.

He said it anyway. “Dismiss your seamstress, Madame. I will make sure she can find no other work in the district. Except the work I have in mind for her.” He chuckled. “On her back.”

“Out, Monsieur ,” Maman told him, her voice taut with anger and distress.

“Better yet,” said the viscount, “Convince her to be my mistress, and I will allow you to live rent free for as long as the arrangement continues. I will even give you a sum of money for yourself. I cannot say fairer than that.” He sounded very pleased with himself.

“ Monsieur !” Maman’s voice was sharp. Jackie wanted to peek, but she did not want the viscount to see her.

The viscount’s voice was harsh in response. “I will leave, but remember what I have said. If you cannot pay me, one way or another, you will be out on your ear. You, and your seamstress.” The last word was cut off as Maman shut the door with a bang.

Jackie opened the workroom door just as Maman sank onto their parlor chair—the white one with the ornate carving and luxurious padding that was just for customers. When she caught sight of Jackie, she held out her hand.

“Jaqueline! Ma cherie . Did you hear that? That cochon !” She moaned. “Double the rent!”

“I am sorry I was late home, Maman. There was a horse…”

“ Ca ne fair rein . The cochon searched for you. It was good you were not here, ma cherie . Double the rent!”

“Can he do that?” Jackie asked. “Surely we can appeal to the law?”

Maman turned to French entirely, which Jackie recognized as a measure of her distress, for though her English still echoed with the intonations of her birth language, and she peppered her speech with French expressions, she generally insisted she and Jackie spoke English unless they were alone in the evening. It was a habit she and Papa had adopted during the long war with France, to stop some villager from denouncing them as spies because they said things that others could not understand.

“Who is to stop that cochon ?” she asked, in French. “He and his mere —they own this village. Will the magistrate believe me instead of the viscount? He is an English nobleman. What am I? A Frenchwoman and a seamstress. Never mind that my family and your father’s are far more noble than his. Besides, the magistrate is friends with the viscountess.”

The magistrate, if village gossip told true, was the viscountess’s lover. But Maman would never mention such a thing to any unmarried girl, let alone her daughter.

“What of Mr. Allegro, Maman?” Jackie asked. Mr. Allegro was the viscount’s cousin, secretary, and assistant to the steward. But if he had any influence with either the viscount or his mother, Jackie had never heard of it, and apparently neither had Maman, because she dismissed the secretary with a shake of her head.

“How much do we have, Maman?” Jackie asked.

“Not enough, Jacqueline. Not nearly enough. Even at the old rate, the quarter’s rent depends on Lady Riese paying her bill, and each time I present it, she complains, or orders something else, or makes another delay.” She shrugged, her shoulders slumping in despair. “Double it, in just five days? It cannot be done.”

Well then. They would need to make up the difference. Jackie knew how and where if she could just nerve herself to do it. The Crown and Pumpkin had a high stakes gambling room once a week that attracted the gentlemen of the district. Jack Le Gume had been avoiding it, because they were dangerous men, and if they recognized her as a woman, she was unlikely to escape an even worse situation than the one Viscount Riese intended.

“We must sell the cow,” Maman decided.

“Bessie, Maman? Sell Bessie?” They had bought the cow as a heifer when they first moved here, when Jackie was fourteen, shortly after they’d lost Papa. Bessie was not just their cow; she was Jackie’s friend.

“She is giving less and less milk, Jackie. She needs to be put to a bull, and no one will allow us to rent theirs.” Because of the viscount, Jackie was sure. Ever since she refused his first offer, he had been finding ways to make it hard for Maman and Jackie to make ends meet. Though at least he had not been able to prevent the ladies of the district from employing Maman, who was the best modiste for at least a day’s journey.

“Nor can we afford to have her eating the grass and giving us nothing in return,” Maman pointed out. “She needs a new home where there is a bull with the herd, and we need the money. Then, when the rent is paid, we can perhaps buy a goat or two.”

Jackie argued, but Maman would not be moved. “Enough. Tomorrow, there is a market in Civerton. Jackie Bean shall take Bessie to market, for a boy shall be safer than a girl. Get the best price you can for her, cherie .”