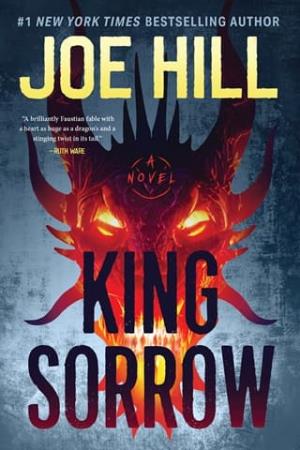

King Sorrow

Chapter 1

One

On the first weekend in September, Arthur Oakes drove west to see his mother in the House of Correction. It was a trip of

more than two hundred miles, across the southern half of Maine, the chimney pipe of New Hampshire, and into Vermont, and it

ended, as it always did, in a line of cars waiting to pass through a twelve-foot-high gate topped with barbed wire.

Arthur always thought the House of Correction looked like a high school: a three-story block of sandstone brick, with narrow

slots for windows. He slowed to a stop behind a Ford Ranchero disgorging oily black smoke from the exhaust pipe. A bumper

sticker read: no free rides—gas, grass, or ass. There was a bumper sticker a man could respect. Arthur’s VW had been his mother’s ride before it was his, and the Rabbit

had bumper stickers too . . . a lot of them.

His mother hadn’t let a square inch of the rear end go to waste.

One said are you following jesus this close?

Another showed a picture of Gandhi and said an eye for an eye makes the whole world blind.

They should’ve locked her up for crimes against her own car.

It grated on him, parking his inherited Christmobile in a lot

full of vehicles that had probably seen action as getaway cars.

If the exterior of the Black Cricket Women’s House of Correction looked like a big public high school, the lobby resembled

a cramped ER waiting room. Fluorescent lights buzzed and cast a dispiriting, impoverished glow. A TV set played daytime talk.

A guard, a heavyset woman with a butch haircut, piloted a rolling office chair behind a scratched, dirty window.

Arthur joined the queue, behind a couple in their mid-twenties and a teenage girl.

The guy wore black jeans, tight to his stovepipe legs, a sleeveless black Harley tee, and a do-rag.

His lady leaned against him, a woman with hard, bony features that she had tried to soften with blusher and bubblegum-pink lipstick.

The teenager stood close by, head down, face hidden behind her own unwashed yellow hair.

She had on a Guns N’ Roses tee that was too small for her, exposing her midriff.

Her acid-washed jeans sagged to reveal the top of her shiny black thong.

Arthur looked away, felt somehow it was indecent to have noticed.

“She can’t go in there wearing that shirt,” said the officer behind the window. She pointed at the teenager.

The girl craned her neck to peer down at her GN’R shirt, as if to hunt for an offensive stain, and Arthur realized, with a

jolt, that he knew her . . . not by name but by profession. She delivered pizzas for Shut-Up-And-Eat-It Pizza in Podomaquassy—and

marijuana or ’shrooms as well, if you knew what to order, and Arthur’s roommate, Donovan McBride, did. She turned up at their

off-campus student housing once or twice a month to bring Van a sausage pie and a baggie of green. Arthur figured she hooked

half the campus up with weed and indigestion.

“What’s wrong with it?” the pizza girl asked.

“No references to firearms. Cover it up or take it off.”

“You’d like that, wouldn’t you?” the older sister asked. She put the pizza girl in a headlock and squeezed one breast. “Get

an eyeful of Tana’s melons.” Tana shrieked and twisted free.

The guard let her bored gaze drift away. “The rules are right there on the wall.”

Tana rubbed her breast and said, “It’s a concert shirt.”

“I see a pair of crossed pistols. Garments displaying drugs, weapons, or obscenities are not allowed in the House of Correction.

Volpe, Nighswander, you’re cleared to enter. Your sister will have to stay here.” The guard tipped her head toward the double

doors on the left.

“My sis is coming with us, lez,” said the older sister.

“What’s that?” asked the officer. She cocked her head, turning her ear to the glass. Arthur thought it possible she genuinely hadn’t heard.

“Jayne,” Tana said, “I’ll wait in the truck. Whatever. You and Ronnie can talk to Mom. You don’t need—”

“Don’t start tellin’ me what I need. You’re the whole reason we’re here,” Jayne Nighswander said. She turned her attention

back to the officer. “I hadda get up at six in the goddamn morning to drive Tana here so she could explain her latest fuck-up

to our mother. And you’re gonna make her sit in the truck because you don’t like her shirt?”

The officer stood. One hand fell to the baton on her belt.

“You want to spend time with your mother,” she said, “keep running your mouth. We might be able to arrange a cell right next

to her.”

“Six in the mornin’,” Jayne went on. “Three-hour drive and I gotta knock heads with a fascist dy—”

“She can have my hoodie,” Arthur spoke over her before she could say dyke and get her pointy, narrow head knocked in.

It was the girl, Tana, who impelled him to pipe up. She had shut her eyes, lowered her chin to her chest, and hunched her

shoulders like a kid listening to Mom and Dad fight. In that moment, she looked not nineteen, but a terrorized nine, and Arthur

couldn’t bear it.

Jayne Nighswander looked Arthur over. Arthur couldn’t quite track the emotions that flickered through her pale blue eyes.

He saw something like curiosity, an instant of cold reptilian calculation, and finally, a gleam of amusement.

The ugly color began to drain from the security guard’s face and she settled back into her chair. “As long as I don’t see

guns, I don’t see a problem.”

Arthur wriggled out of his hoodie and slipped it off. It had belonged to his mother and he still sometimes imagined it smelled

of her, the smell of the chapel: old hymnals and pine pews. On the back was an outline of Africa with Steve Biko’s face peering

out from within.

Tana Nighswander didn’t thank him. She kept her head down as she pulled it on, never even looked at him. The boyfriend, Ronnie Volpe, admired the back of the sweatshirt and then said, in a hoarse, smoker’s voice, “Eddie Murphy! I love that absurd motherfucker.”

The security officer jerked a thumb at the door. “Go on. Next.”

As the three of them moved away, Jayne Nighswander looked back at him and flashed a wolfish grin. “That was damn big of you,

bud. We’ll have to pay you back someday.” She ushered Volpe and her sister through the doors and out of sight.

The guard behind the Plexiglas window was shaking her head, her jaw tight.

“I’m here to see my mother, Dr. Erin Oakes,” Arthur said.

“Yeah, I know who you’re here to see. The holy mother.” She pushed a clipboard at him. “Sign here, dumbass.” She muttered

this last bit to herself, but Arthur caught it all the same, and then wondered if he had misheard.

“What?”

“Why’d you do that?” she asked him. She sounded genuinely aggrieved. “Why’n’t you mind your own business?”

“Oh,” Arthur said, “I don’t know. Just trying to help. It’s what my mother would’ve done.”

“Buddy,” said the security guard, “if your mother made such great choices, do you think she’d be in here?”