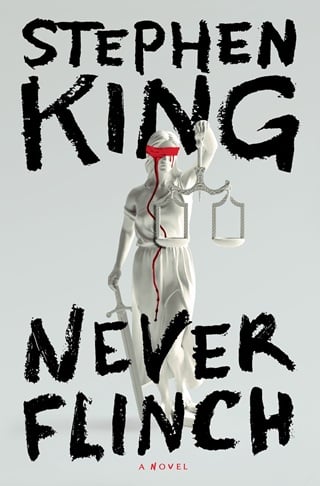

Never Flinch (Holly Gibney #4)

Chapter 1

1

It’s April now. In the Second Mistake on the Lake, the last of the snow is finally melting.

Izzy Jaynes gives a one-knuckle courtesy knock on her lieutenant’s door and goes in without waiting. Lewis Warwick is tilted back in his chair, one foot resting on the corner of his desk, hands loosely clasped on his midsection. He looks like he’s meditating or dreaming awake. For all Izzy knows, he is. At the sight of her he straightens and puts his foot back on the floor where it belongs.

“Isabelle Jaynes, ace detective. Welcome to my lair.”

“At your service.”

She doesn’t envy him his office, because she’s aware of all the bureaucratic bullshit that comes with it, accompanied by a salary bump so small it might be called ceremonial. She’s happy enough with her humble cubicle downstairs, where she works with seven other detectives, including her current partner, Tom Atta. It’s Warwick’s chair that Izzy lusts after. With its high, spine-soothing back and reclining feature, it’s meditation-ready.

“What can I do for you, Lewis?”

He takes a business envelope from his desk and hands it to her. “You can give me an opinion on this. No strings attached. Feel free to touch the envelope, everybody from the postman to Evelyn downstairs and who knows who else has had their paws on it, but the note should maybe be fingerprinted. Partly depending on what you say.”

The envelope is addressed in capital block letters to DETECTIVE LOUIS WARWICK at 19 COURT PLAZA. Below the city, state, and zip, in even larger capitals: CONFIDENTIAL!

“What I say? You’re the boss, boss.”

“I’m not passing the buck, it’s my baby, but I respect your judgement.”

The end of the envelope has been torn open. There’s no return address. She carefully unfolds the single sheet of paper inside, holding it by the edges. The message has been printed, almost certainly on a computer.

To: Lieutenant Louis Warwick

From: Bill Wilson

Cc: Chief Alice Patmore

I think there should be a corollary to the Blackstone Rule. I believe the INNOCENT should be punished for the needless DEATH of an innocent. Should those who caused that death be put to death themselves? I think not, because then they would be gone and the suffering for what they did would be at an end. This is true even if they acted with the best will in the world. They need to think about what they did. They need to “Rue the Day.” Does that make sense to you? It does to me, and that is enough.

I will kill 13 innocents and 1 guilty. Those who caused the innocent to die will therefore suffer.

This is an act of ATONEMENT.

Bill Wilson

“Whoa,” Izzy says. Still being careful, she refolds the note and slips it back into the envelope. “Someone has donned their crazy pants.”

“Yes indeed. I googled the Blackstone Rule. It says—”

“I know what it says.”

Warwick puts his foot up on the desk again, hands this time laced together at the nape of his neck. “Elucidate.”

“Better for ten guilty men to go free rather than for one innocent man to suffer.”

Lewis nods. “Now for Double Jeopardy, where the scores can really change. What innocent man might our crazy-pants correspondent be talking about?”

“At a guess, I’d say Alan Duffrey. Shanked last month at Big Stone. Died in the infirmary. Then that podcaster, Buckeye Brandon, blowing off his bazoo, and the follow-up piece in the paper. Both about the guy who came forward to say he framed Duffrey.”

“Cary Tolliver. Got hit with the cancer stick, late-stage pancreatic, and wanted to clear his conscience. Said he never intended Duffrey to die.”

“So this note isn’t from Tolliver.”

“Not likely. He’s in Kiner Memorial, currently circling the drain.”

“Tolliver making a clean breast was sort of like locking the barn door after the horse was stolen, wouldn’t you say?”

“Maybe yes, maybe no. Tolliver claims he fessed up in February, days after he got his terminal diagnosis. Nothing happened. Then, after Duffrey was killed, Tolliver went to Buckeye Brandon, aka the outlaw of the airwaves. ADA Allen says it’s all attention-seeking bullshit.”

“What do you think?”

“I think Tolliver makes a degree of sense. He claims he only wanted Duffrey to do a couple of years. Said Duffrey going on the Registry would be the real punishment.”

Izzy understands. Duffrey would have been forbidden to reside in or near child safety zones—schools, playgrounds, public parks. Forbidden to communicate with minors by text, other than his own children. Forbidden to have pornographic magazines or access porn online. Have to inform his supervising officer of an address change. Being on the National Sex Offender Registry was a life sentence.

If he had lived, that was.

Lewis leans forward. “Blackstone Rule aside, which really doesn’t make much sense, at least to me, do we have to worry about this Wilson guy? Is it a threat or empty bullshit? What do you say?”

“Can I think it over?”

“Of course. Later. What does your gut tell you right now? It stays in this office.”

Izzy considers. She could ask Lew if Chief Patmore has weighed in, but that’s not how Izzy rolls.

“He’s crazy, but he’s not quoting the Bible or The Protocols of the Elders of Zion . Not suffering Tin Hat Syndrome. Could be a crank. If it isn’t, it’s someone to worry about. Probably someone close to Duffrey. I’d say his wife or kids, but he didn’t have either.”

“A loner,” Lewis says. “Allen made a big deal of that at the trial.”

Izzy and Tom both know Doug Allen, one of the Buckeye County ADAs. Izzy’s partner calls Allen a Hungry Hungry Hippo, after a board game Tom’s children like. Ambitious, in other words. Which also suggests Tolliver may have been telling the truth. Ambitious ADAs don’t like to see convictions overturned.

“Duffrey wasn’t married, but what about a partner?”

“Nope, and if he was gay, he was in the closet. Deep in the closet. No rumors. Chief loan officer at First Lake City Bank. And we’re assuming it’s Duffrey this guy’s talking about, but without a specific name…”

“It could be someone else.”

“Could be, but unlikely. I want you and Atta to talk to Cary Tolliver, assuming he’s still in the land of the living. Talk to all Duffrey’s known associates, at the bank and elsewhere. Talk to the guy who defended Duffrey. Get his list of known associates. If he did his job, he’ll know everyone Duffrey knew.”

Izzy smiles. “I suspect you wanted a second opinion that echoes what you already decided.”

“Give yourself some credit. I wanted the second opinion of Isabelle Jaynes, ace detective.”

“If it’s an ace detective you want, you should call Holly Gibney. I can give you her number.”

Lewis lowers his foot to the floor. “We haven’t sunk to the level of outsourcing our investigations yet. Tell me what you think.”

Izzy taps the envelope. “I think this guy could be the real deal. ‘The innocent should be punished for the needless death of an innocent’? It might make sense to a nut, but to a sane person? I don’t think so.”

Lewis sighs. “The really dangerous ones, the ones who are crazy and not crazy at the same time, they give me nightmares. Timothy McVeigh killed over a hundred and fifty people in the Murrah Building and was perfectly rational. Called the little kids who died in the daycare collateral damage. Who’s more innocent than a bunch of kids?”

“So you think this is real.”

“ Maybe real. I want you and Atta to spend some time on it. See if you can find someone so outraged by Duffrey’s death—”

“Or so heartbroken.”

“Sure, that too. Find someone mad enough—I mean it both ways—to make a threat like this.”

“Why thirteen innocent and one guilty, I wonder? Is that a total of fourteen, or is the guilty one of the thirteen?”

Lewis shakes his head. “No idea. He could have picked the number out of a hat.”

“Something else about this letter. You know who Bill Wilson was, right?”

“Rings a faint bell, but why wouldn’t it? Maybe not as common as Joe Smith or Dick Jones, but not exactly Zbigniew Brzezinski, either.”

“The Bill Wilson I’m thinking of was the founder of AA. Maybe this guy goes to AA and he’s tipping us to that.”

“Like he wants to be caught?”

Izzy shrugs, sending him a no opinion vibe.

“I’ll send the letter to forensics, much good it’ll do. They’re going to say no fingerprints, computer font, common form of printer paper.”

“Send me a photo of it.”

“I can do that.”

Izzy gets up to go. Lewis asks, “Have you signed up for the game yet?”

“What game?”

“Don’t play dumb. Guns and Hoses. Next month. I’m going to captain the PD team.”

“Gee, I haven’t got around to that, boss.” Nor does she mean to.

“The FD has won three in a row. Going to be a real grudge match this year, after what happened last time. Crutchfield’s broken leg?”

“Who’s Crutchfield?”

“Emil Crutchfield. Motor patrolman, mostly works on the east side.”

“Oh,” Izzy says, thinking, Boys and their games .

“Didn’t you used to play? At that college you went to?”

Izzy laughs. “Yeah. Back when dinosaurs walked the earth.”

“You should sign up. Think about it.”

“I will,” Izzy says.

She won’t.

2

Holly Gibney raises her face into the sun. “T.S. Eliot said April is the cruelest month, but this doesn’t seem very cruel to me.”

“Poetry,” Izzy says dismissively. “What are you having?”

“Fish tacos, I think.”

“You always have fish tacos.”

“Not always, but mostly. I’m a creature of habit.”

“No shit, Sherlock.”

Soon one of them will get up and join the line at Frankie’s Fabulous Fish Wagon, but for the time being they just sit quietly at their picnic table, enjoying the warmth of the sun.

Izzy and Holly have not always been particularly close, but that changed after they had dealings with a pair of elderly academics, Rodney and Emily Harris. The Harrises were insane and extremely dangerous. It could be argued that Holly got the worst of it, having to deal with them face to face, but it was Detective Isabelle Jaynes who had to inform many of the loved ones of those who had been victims of the Harrises. She also had to tell those loved ones what the Harrises had done, and that was no night at the opera, either. Both women bore scars, and when Izzy called Holly after the newspaper coverage (national as well as local) died down, asking if she wanted to do lunch, Holly agreed.

“Doing lunch” became a semi-regular thing, and the two women formed a cautious bond. At first they talked about the Harrises, but less so as time went by. Izzy talked about her job; Holly talked about hers. Because Izzy was police and Holly a private investigator, they had similar, if rarely overlapping, areas of interest.

Nor had Holly entirely given up the idea of luring Izzy over to the dark side, especially since her partner, Pete Huntley, had retired and left Holly to run Finders Keepers singlehanded (with occasional help from Jerome and Barbara Robinson). She was at pains to tell Izzy that Finders didn’t do divorce work. “Keyhole peeping, social media tracking. Text messages and telephoto lenses. Oough.”

When Holly brought up the possibility, Izzy always said she’d keep it in mind. Which meant, Holly thought, that Iz would put in her thirty on the city police force and then retire to a golfside condo in Arizona or Florida. Probably on her own. A two-time loser in the marriage sweepstakes, Izzy said she wasn’t looking for another hookup, especially of the marital variety. How, she said to Holly during one of their lunches, could she come home and tell her husband about the human remains they had found in the Harrises’ refrigerator?

“Please,” Holly had said on that occasion, “not while I’m trying to eat.”

Today they’re doing lunch in Dingley Park. Like Deerfield Park on the other side of the city, Dingley can be a rather sketchy environment after dark ( a fucking drug mart is how Izzy puts it), but in the daytime it’s perfectly pleasant, especially on a day like this. Now that warm weather is on the come, they can eat at one of the picnic tables not far from the firs that circle the old ice rink.

Holly is vaccinated up the ying-yang, but Covid is still killing someone in America every four minutes, and Holly doesn’t want to take chances. Pete Huntley is even now suffering the aftereffects of his bout with the bug, and Holly’s mother died of it. So she continues to take care, masking up in close indoor situations and carrying a bottle of Purell in her purse. Covid aside, she likes dining al fresco when the weather is nice, as it is today, and she’s looking forward to her fish tacos. Two, with extra tartar sauce.

“How’s Jerome?” Izzy asks. “I saw that book about his hoodlum great-grandfather landed on the bestseller list.”

“Only for a couple of weeks,” Holly says, “but they’ll be able to put New York Times Bestseller on the paperback, which will help the sales.” She loves Jerome almost as much as she loves his sister, Barbara. “Now that his book tour is over, he’s been asking to help me around the shop. He says it’s research, that his next book is going to be about a private eye.” She grimaces to show how much she dislikes the term.

“And Barbara?”

“Going to Bell, right here in town. Majoring in English, of course.” Holly says this with what she believes is justifiable pride. Both Robinson sibs are published authors. Barbara’s book of poems—for which she won the Penley Prize, no small hill of beans—has been out for a couple of years.

“So your kids are doing well.”

Holly doesn’t protest this; although Mr. and Mrs. Robinson are alive and perfectly fine, Barb and Jerome sort of are her kids. The three of them have been through the wars together. Brady Hartsfield… Morris Bellamy… Chet Ondowsky… the Harrises. Those were wars, all right.

Holly asks what’s new in Blue World. Izzy looks at her thoughtfully, then asks, “Can I show you something on my phone?”

“Is it porno?” Izzy is one of the few people Holly feels comfortable joking with.

“I guess in a way it is.”

“Now I’m curious.”

Izzy takes out her phone. “Lewis Warwick got this letter. So did Chief Patmore. Check it out.”

She passes the phone to Holly, who reads the note. “Bill Wilson. Huh. You know who that is?”

“The founder of AA. Lew called me into his office and asked for my opinion. I told him I’d err on the side of caution. What do you think, Holly?”

“The Blackstone Rule. Which says—”

“Better ten guilty go free rather than one innocent suffer. Blackstone was a lawyer. I know because I took pre-law at Bucknell. Do you think this guy might be in the legal profession?”

“Probably not a good deduction,” Holly says, rather kindly. “I never took a law course in my life, and I knew. I’d put it in the category of semi-common knowledge.”

“You’re a sponge for info,” Izzy says, “but point taken. Lew Warwick at first thought it came from the Bible.”

Holly reads the letter again. She says, “I think the man who wrote this could be religious. AA puts a lot of emphasis on God—‘let go and let God’ is one of their sayings—and the alias, plus this thing about atonement… that’s a very Catholic concept.”

“That narrows it down to, I’m going to say, half a million,” Izzy says. “Big help, Gibney.”

“Could this person be angry about, just a wild guess, Alan Duffrey?”

Izzy pats her palms together in quiet applause.

“Although he doesn’t specifically mention—”

“I know, I know, our Mr. Wilson doesn’t mention a name, but it seems the most likely. Kiddie fiddler killed in prison, then it comes out he maybe wasn’t a kiddie fiddler after all. The timing fits, more or less. I’m going to buy your tacos for that.”

“It’s your turn, anyway,” Holly says. “Refresh me on the Duffrey case. Can you do that?”

“Sure. Just promise you won’t steal it from me and figure out who Bill Wilson is on your own.”

“Promise.” Holly means it, but she’s engaged. This is the sort of thing she was born to do, and it’s led her down some strange byways. The only problem with her day-to-day workload is that it involves more filling out forms and talking to bail bondsmen than solving mysteries.

“Long story short, Alan Duffrey was the chief loan officer at the First Lake City Bank, but until 2022 he was just another loan department guy in a cubicle. It’s a very big bank.”

“Yes,” Holly says. “I know. It’s my bank.”

“It’s also the Police Department’s bank, and any number of local corporations, but never mind that. The chief loan officer retired, and two men were in competition for the job, which meant a hefty salary bump. Alan Duffrey was one. Cary Tolliver was the other. Duffrey got the job, so Tolliver got him sent to prison for kiddie porn.”

“That seems like an overreaction,” Holly says, then looks surprised when Izzy bursts out laughing. “What? What did I say?”

“Just… that’s you, Holly. I won’t say it’s what I love about you, but I may come to love it, given time.”

Holly is still frowning.

Izzy leans forward, still smiling. “You’re a deductive whiz-kid, Hols, but sometimes I think you lose your grip on what criminal motivation really is, especially criminals with their screws loosened by anger, resentment, paranoia, insecurity, jealousy, whatever. There was a monetary motive for what Cary Tolliver says he did, of course there was, but I’m sure other things played a part.”

“He came forward after Duffrey got killed, didn’t he?” Holly says. “Went to that podcaster who’s always digging dirt.”

“He claims he came forward before Duffrey was killed. In February, after getting a terminal cancer diagnosis. Wrote the ADA a confession letter and claims the ADA sat on it. So he eventually spilled everything to Buckeye Brandon.”

“That could be your atonement motive.”

“He didn’t write this,” Izzy says, tapping the screen of her phone. “Cary Tolliver’s dying, and it won’t be long. Tom and I are going to interview him this afternoon. So I better get our lunch.”

“Extra tartar sauce for me,” Holly says as Izzy gets up.

“Holly, you never change.”

Holly looks up at her, a small woman with graying hair and a faint smile. “It’s my superpower.”