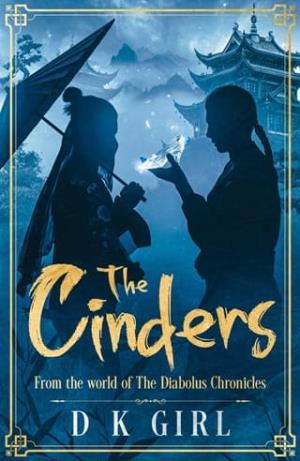

The Cinders (The Diabolus Chronicles)

Chapter One

ONCE UPON a time, Prince Xian had freely roamed the wide corridors and sweeping gardens of the Imperial Palace.

As a child he’d had no cares but for chasing butterflies, or trying to catch the goldfish swimming in streams that ran like crystal ribbons through the palace grounds.

He would bring them to his mother in glass jars, gifts to make her smile, preening like a peacock beneath her words of praise and endearment.

‘My bao bao huli.’

The first time she had called him her baby fox, Xian had stamped his tiny foot at being named after such a sly creature. But then his mother had told him of their virtues.

‘They are swift and agile and clever, and such a beautiful thing to behold, with their blazing red fur and jet black nose.’

He’d not been convinced at first; hearing how often the groundsmen lamented the loss of their pheasants and quails. But it pleased his mother to call him huli, and Xian grew to delight in the name.

Now, many years later, and thousands of miles from the Forbidden City, his mother’s voice was more dream than memory, and Xian did not feel clever at all. Nor beautiful.

But he could claim to be sly as a fox, for he was adept at pretending he was not tired when he was exhausted, and serene when his nerves were frayed.

He sat now at his dresser, spine rigid, shoulders pulled back, his hands folded in his lap. He’d not give the woman who attended him any reason to spread yet more rumours. If he so much as showed a flicker of nerves, callous and untrue words would be spoken about him.

The attendant worked in silence on his long black hair, oiling its tips to give them weight, and setting hair combs over the crown of his head to prevent it straying into his eyes when he danced at the evening’s ceremony.

How he wished to be as free as that fox his mother had named him after; following its nose wherever it pleased.

He’d certainly not have let it lead him here, to Kunming, in the far-flung province of Yunnan, where his guardians found no love in their hearts, nor a true home for him in their vast manor.

A comb’s wooden tooth found his scalp, and a startled whimper escaped him. The attendant bowed her head. ‘Forgive me, your highness.’

She wouldn’t dare allow her eyes to meet his; lest his violet gaze curse her.

Xian tapped his bare heel against the wood flooring, his nerves sharp and jangling, his stomach empty but for roiling unease.

Ever since the envoy from Manhao had arrived the day before, trepidation had gripped him, and only worsened after his dawn encounter with the marchioness this morning.

Marchioness Shen had returned from her prayers early, cornering him as he finished clearing the ashes from the fireplace that heated the kang in her sleeping room.

His guardian despised any hint of the cold; the heated platform in her chamber was the largest of any kang in the entire manor.

The bucket of last night’s cinders had been heavy in his hands.

‘You will dance the yayue tonight as though you dance for the emperor himself.’ She spoke reverently of the ancient performance—a theatre of music, and powerful, flowing dance, that sealed official treaties.

‘Sub-Prefect Keng could not travel from Manhao himself, but the eyes of his most trusted officials will be on you, and let them not speak of anything but your fortunate excellence.’

‘Yes, your grace.’ Xian kept his eyes lowered; knowing her gaze would hold only its usual disdain.

‘Like many fools he is charmed by word of the Dancing Prince, thinking you gifted, and the perfection of your dance a measure of the good fortune that will surround our treaty with Manhao. But you and I both know your skill is unnatural. Not given by the gods but by the evil spirits of sorcery.’

‘Yes, your grace.’ He’d long ago given up protesting against both conflicting accusations; that he bore a curse, but his ethereal dance was a talisman of fortune.

The marchioness made it clear enough which of those she believed.

She’d leaned in close, her orange blossom perfume too heavily applied, and remnants of the crushed pearls she applied to her face each morning visible beneath her earlobe.

‘I’m trying my best, I truly am, to keep your mother’s dark blood from taking you over.

Do not think I enjoy having you toil so long and so hard, but what else is to be done?

We must keep you humbler than your mother ever was. ’

His throat had been too tight to reply, and tears too close. No matter the years that had passed since the fire that took his mother and scarred him forever, he felt her loss keenly.

‘Please the Sub-Prefect’s envoy with your performance and make it your finest,’ the Marchioness had hissed.

‘This agreement we make with Manhao will bring great fortune to Kunming, and that prosperity will bring the Lady Tian’s marriage prospects within reach of the Imperial Palace. Do not cause your sister’s ruin.’

Xian could not cause ruin to a sister he did not have. In the Forbidden City, he’d had many siblings. But not here. Lady Tian Yu Ming had not spent a single day of the past ten years behaving like a sister towards him, and only called him brother because she knew he hated it so.

‘I will not disappoint you, Marchioness Shen.’

‘No. You will not, for if you do, I shall send word to my sister that His Majesty’s unlucky son brings him more shame. She will tell him how you have disrespected his show of mercy, and dishonoured those who care for you with the utmost diligence, despite all the troubles you bring.’

The threat was many hours past now, but even as he sat here in his finery, those cruel words still made him hollow.

The attendant slid in the final comb; this one centred over his forehead with seven beaded lengths dangling from it.

The strings were decorated with tiny sea pearls, silver links and pink coral to contrast his russet gown.

This decorative headpiece hung over his face veil, his favourite; a black chiffon that covered him from beneath his eyes and hung almost to his collarbone, secured with silver loops around his ears.

Simple and practical; his scars were nicely hidden beneath the breathable fabric.

He peered through the hanging lengths and was reminded of a bird staring out through the bars of its cage.

Xian planted his restless feet to the ground, his breath catching.

‘Thank you,’ he said. ‘Would you leave me now please.’

‘But…your highness, I…I am to take you to Her Grace once you are dressed.’ She was frightened of him, he knew, with all the talk of being cursed, but like so many in the household she was far more fearful of her mistress. He understood that trepidation all too well.

‘You have done your job admirably and in good time,’ he said. ‘I would like a few moments to pray…and prepare myself for the proceedings.’

He’d not be praying. He’d not be staying in this room, with its pressing walls and orange blossom incense.

‘Highness, I am instructed to tell Her Grace the moment you are ready.’

‘And you shall.’ His whole body vibrated, his lungs tight, with a plan that was both mad and necessary.

Xian longed to see the only companion he trusted without reserve.

Her calming presence would ease his troubled mind.

‘I will not be long, I promise you. A quarter of the hour, if not less, then we shall go. Wait in my library, I will come and find you there when I am done.’

Her silence stretched thin before she replied. ‘Yes, your highness. I’ll wait for you, for the quarter hour.’

Not a moment more, he thought, and she’d be running to the marchioness with word of a prince’s pathetic rebellion. But he could not breathe properly in this room any longer.

He waited, listening to her footsteps, the slide of the panelling as she left the room, the soft padding of her feet down the hall.

When she was far enough away, Xian was on his feet, hurrying to put on his slippers, sliding back the door that led him out onto the low veranda, and down the short flight of steps into the garden.

He moved beneath the late winter sun, taking deep gulping breaths of cold air, and took the path running in the opposite direction to the shrine he’d claimed to need.

Xian wasn’t sure which he was more terrified of; performing under the glare of nobles and dignitaries, or being found in his finery amongst the nanmu trees and punished for it.

He moved carefully around an old-blush rose bush, pruned and bare of flowers, but its gnarled branches still more than capable of tearing at the copious layers of his gown.

Within a few paces he realised the danger posed to his pristine clothing; not only from the reaching limbs of the foliage, but from a garden touched by overnight rain.

He bunched up his skirts, the swing of the beading at his face as frustrating as a swarm of gnats.

Xian moved quickly, furtively, feeling much more like a sly fox. And looking like one, too.

His ceremonial clothing was dyed a shade of russet with black trim. The colour was to honour the Marquess and Marchioness’s guests; a trade envoy who had travelled from Manhao, a port city on the Red River.

The silk and chiffon high-collared ruqun, stiff with newness, had only been delivered to him that morning. The ruqun was mostly worn by women, its favour among men fading with past dynasties. Likely, the marchioness intended this as a subtle act of humiliation.

But the seamstress, one of the rare few in the manor who was not openly wary of Xian, had adjusted the ensemble to suit his dancing needs, and as he’d listened to her evident pride in her work, he’d felt anything but humiliated.