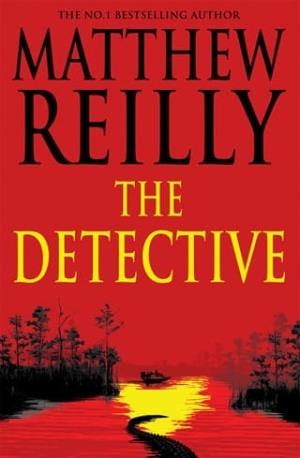

The Detective

PROLOGUE THE BABY IN THE DOLL

PROLOGUE

THE BABY IN THE DOLL

It came late in the season and it lasted three days.

Storms can hide things.

They can also reveal them.

Lost things.

Secret things . . .

Victorville, Louisiana

1 October

The three boys found it when they’d been searching for the missing house.

Yes, a missing house.

See, during the hurricane the water level of the Acheron River rose so high that Old Man Hutchins’s whole house was lifted off its mountings and just floated away downstream.

Fortunately for Old Man Hutchins, he wasn’t in it at the time.

He’d been evacuated a few days earlier.

So when the rains finally stopped, the boys went off in a beat-up tin-can motorboat in search of the missing house.

It was the kind of adventure that’s appealed to kids since the dawn of time: to go out after a hurricane or flood and explore the wreckage.

And hurricanes in the Gulf fling all kinds of strange stuff every which way.

Highway signs. Trawler cranes. Fuel barges. Shipping containers.

The boys had travelled up the vast swamp from Hackberry, where they lived. They could’ve started their search from Victorville in the north and come downriver, but that would’ve meant driving all the way round the wetlands to get to Victorville and they didn’t have driver’s licences yet.

Then they found it.

It was half-sunk in the swollen river, pressed up against the trunk of a big gnarled tree.

The two-storey building sat dumbly in the water, tilted dramati-cally sideways, its doors and windows flung open, allowing the slow-moving river to flow into and out of it.

In regular times, Old Man Hutchins’s home had looked haunted.

Now it looked worse.

The three boys gaped at it in awe.

‘We should go inside,’ the youngest of the three, fourteen-year-old Bobby Joe Bowman, whispered.

‘Yeah,’ said his friend, Lee Pruitt.

A splash nearby.

A thick black pebbled tail went under.

The boys spun.

Ripples in the water.

Then the cause of the disturbance surfaced.

A fourteen-foot-long gator—almost twice the size of their little boat.

It cruised lazily into the house.

‘Maybe not just yet,’ Bobby Joe said.

The house was beached across from the mouth of Dead Man’s Creek, a small snaking dirt-walled creek bed that had got its name in the 1800s on account of some tale about a slave who’d been shot in the creek while escaping from a plantation.

He’d cursed the -slavers and their land before they shot him.

The creek had been a foul boot-sucking bog ever since.

The boys never went up it.

An older boy at school named Jerome Spruce claimed he’d once gone two-hundred yards up Dead Man’s Creek and glimpsed the wreck of a rusty old spud barge up there, mounted beside a gator pond.

Jerome said he saw Crazy Eli Gage sitting on the deck of the barge underneath a torn Confederate battle flag.

Then Eli—toothless and wiry—had spotted Jerome and fired his shotgun, shouting, ‘Who’s that there?’ and Jerome had run for his life.

The recent storm had been so strong, however, that Dead Man’s Creek had become, like all of the other backwater tributaries in these parts, a raging torrent that had gushed out into the Acheron River.

The whole area stank like a sewer.

Oil slicked the river. The Kingman petrochemical plant wasn’t far from here.

The three boys circled the house in their tin boat.

And they saw it.

It was just above the waterline, lying on the sloping side of the house, just resting there.

A doll.

Plastic, dirty and old.

Its eyes had the unnerving blank stare of vintage dolls everywhere.

Only this one came with another unsettling feature.

It had been crucified to a small wooden cross.

The three boys were transfixed.

‘Go on, Lee, grab it,’ Bobby Joe said.

‘You grab it,’ Lee said. ‘Thing gives me the creeps.’

‘I ain’t touchin’ it,’ Bobby Joe said. ‘Will, you’re the oldest. You do it.’

Not wanting to appear frightened in front of his younger companions, fifteen-year-old Will Schuman reached out from their little boat and plucked the crucified doll from the house.

He frowned instantly.

‘It’s heavy. There’s somethin’ inside it.’

He bounced it in his hand, gauging the weight.

He pulled the head off the doll, and all three boys screamed.

Inside the doll—almost form-fitting inside it—was a dead baby girl.

It was dark by the time the boys reached the sheriff’s office back in Hackberry.

As they’d hurried there, they’d chatted excitedly about the possibilities of a reward, schoolyard fame and maybe even doing interviews on the local television news.

As it happened, Lee Pruitt’s brother, Tommy—all of -twenty-

three himself—was a newly appointed deputy at the Hackberry Sheriff’s Department and as such was pulling the night shift.

Eager to impress the sheriff, Tommy Pruitt dutifully logged the find and sent the tiny corpse, along with the doll and the wooden cross, to the DNA lab at the Louisiana State Police’s Bureau of Investigations in Lake Charles.

At the lab, a bored opiate-addicted technician performed all the requisite tests.

That was how I came in.

For when the DNA results came back around lunchtime the next day, I received an alert on my phone about them.