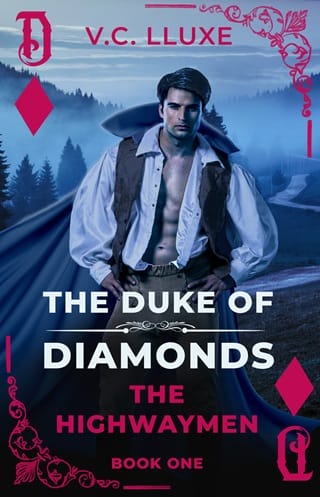

The Duke of Diamonds (The Highwaymen #1)

Chapter One

CHAPTER ONE

PATIENCE NEEDbrOOKE, RECENTLY the Viscountess of Balley, had become accustomed to being struck shockingly quickly in her brief marriage. The first time the viscount had taken his fists to her, she’d been stunned. The second time, she was less so, and by the third time, she was actually rather expecting it.

It wasn’t that she was unaware that certain men behaved in such a manner, of course. If she had decided to complain about it to someone, perhaps her elder brother Mark, the one who’d negotiated this marriage in the first place, she knew she’d be shown the passages in the bible which indicated that she was not to complain.

She must submit to her husband in the Lord, for this was right, and her husband was the head of her, just as Christ was the head of the church, and she was a woman anyway, and her desire was to her husband and he would rule over her.

There was no recourse.

But if her father was still alive, well, he wouldn’t have liked it. Of course, if her father was alive, she likely wouldn’t have been forced into this wretched marriage at all. If her father was alive, he would not have done as her brother had done. Mark had taken all of the family money, gambled half of it away, lost the other half in an ill-advised investment in tobacco, and then found himself nearly penniless and titled. He still had the three estates that were entailed to him, but had no money to support his sister.

Yes, she’d needed to be married off, and Balley had wanted her.

It was done now; no reason to think too hard on what might have been.

Besides, though she kept gingerly touching her chin where his meaty palm had smacked into it earlier today, and though she was thinking she might be bruised (on her face! A bruise on the face, how horrid!) there was reason to be of good cheer.

For one thing, she was leaving her husband for a span of some weeks to spend the rest of the dreadfully hot summer in the country, while her husband stayed to finish out what was left of Parliament’s session in London. The session this year was dragging on and on, likely what was putting her husband in such a bad temper, anyway, and he’d finally decided that it made no sense for her to stay in the heat and stench of the city. She could go on ahead of him to the north, and she would be given a blessed respite from his fist and his open palm.

For another thing, she had not bled this month, which might mean she was with child, and if she was with child, he might stop going at her every night the way he had been and also, perhaps, if she was very clever, she could talk him out of hitting her because it might hurt the child.

So, Patience reminded herself that she had many things to be thankful for that evening as her carriage left London.

She was traveling far later in the day than made any sense, but this was her husband’s fault, too, really. She had meant to leave just after luncheon, had been packed and ready to go, in fact, and he had delayed the business for some hours and then insisted she must stay for dinner, which had necessitated having a dress unpacked from her trunk and having her maid dress her and see to her hair.

Then, she had said that she would simply leave in the morning. It was pointless now. It was late. The sun would be going down—though it was summer, so not until eight o’clock or so. But still, traveling now, at this time of the evening, it was madness.

And that was when Balley, having had too much to drink over the course of the entire day, began to yell at her and call her names. She was sadly quite used to this at this point. She did whatever she could to try to stop him from taking it out upon her, cowering in a corner, agreeing with him slavishly, apologizing, even though she had done nothing wrong.

But then, her little dog, a tiny terrier she had named Dash, had decided to take it upon himself to fearlessly defend his beloved mistress, yapping loudly at Balley, who had first thrown Dash into a wall and then driven a fist into her stomach.

She had cried, “But I have not bled. Don’t hit me there. I could be with child!”

And he had been angry that she had told him not to hit her, so he’d slapped her across the face. Then he’d said, “Get out of my sight. You must take to the road as planned today. I won’t stand for your silliness and indecision, not in my house. You may have been given your way until now, you spoiled chit, but my wife must behave differently.”

She’d heard versions of this speech many times from him.

At any rate, she was leaving London now. They would travel through the night, and she would sleep in the carriage. In the morning, there was a cozy and bright little tavern where they would stop for fresh horses and perhaps for a fresh driver, too, since the one she would have brought would be dead on his feet.

Then they’d be on their way again.

It was all much, much better than it had been, only hours ago. There was no reason to think upon anything except the goodness that lay ahead of her, this was what she told herself.

Truthfully, she would have liked to cry.

She had spent a great number of nights in her brief marriage sobbing. After Balley would leave her bed, after he took his husbandly rights with her, which she had known was supposed to hurt, really, but had thought got less painful with time, except with Balley, it was always frankly brutal and awful. After that, she would often cry. She would turn over and sob into her pillow for three-quarters of an hour or until her tears dried up and she fell asleep.

But usually, after he hit her, she couldn’t cry, because there were servants about, and it simply wasn’t done to cry in front of servants. And just then, she was traveling with her maid, a sweet girl named Isabella, in the carriage, and she could not cry in front of Isabella.

Well, to be truthful, Patience know some people did cry in front of their servants. Perhaps, when she was younger, in her father’s household, she might have done so. But now, in Balley’s household, each of the servants was a spy, terrified of his or her master. He was well within in his rights to hit all of them, after all. They all belonged to him. His servants. His wife. His household. He could do as he liked with them.

So, they had quite the incentive to report to him on her comings and goings. They were rewarded if they did so and punished if they did not. If he found out she was crying all the time, it would not go well for her. Isabella had even said to her once, her eyes quite wide, “Oh, he has asked me to tell him if you are anything but cheerful, and I dare not lie to him. Be cheerful, if you can but manage it, ma’am. Perhaps we may find something cheerful to think of, if we but try.”

Isabella was happy to be leaving London, too, Patience thought.

And Dash, poor Dash, he was asleep on Isabella’s lap. He had not been too damaged by her husband’s fury, but Patience was loath to think of what might happen in the future. She must teach Dash not to bark at her husband, not to protect her.

Of course, that thought made her wish to break out in tears as well.

Abruptly, the carriage stopped.

She furrowed her brow, doing nothing, thinking that they would get moving again in a moment. She looked out the window, but there was nothing to see. It was dusk, and they had just left London, and outside, she could only see the weary-looking waving grasses of a field, stretching all the way out to the setting sun, which looked weary also as it sank below the far, rolling hills.

She waited.

Isabella stood up, smiling brightly, handing over Dash.

Patience took the tiny dog, scratching him just behind his ears, the way he liked it.

Isabella opened the door and poked her head out.

Patience listened as Isabella spoke to the driver.

“It’s some obstruction in the road. A fallen tree, it looks like. Best is to go round, I think. We can easily go through the crossroads to the northwest,” said the driver.

Patience bit down on her lower lip. The crossroads were really the natural way out of London, but no one went that way these days, not unless they were rather desperate, for there were reports of a particularly brutal gang of highwaymen who called themselves the Lords of the Crossroads, and who lay in wait there for unsuspecting carriages and tended to rob them quite blind.

She clutched Dash to her chest and poked her head out as well, right next to Isabella’s. “Is it wise?” she called to the driver. “No one goes through the crossroads anymore.”

The driver took her in. “Yes, my lady, well, we can always go back to the house in town, back to Lord Balley. He won’t be pleased to see us again, however, I can guarantee that.”

She grimaced.

“I think,” said the driver, “if there is any business at the crossroads, we can get through it by offering up some coin or jewels. Is there anything you have handy?”

Patience furrowed her brow. “Pardon me, are you suggesting that we simply pay the highwaymen, as if we are paying a toll?”

“No, not exactly,” said the driver. He sighed heavily. “If your ladyship wishes us to turn back, we shall do it. Is that your wish?”

She licked her lips. She touched her jaw gingerly.

“Aye,” said the driver. “It’ll be another toll taken from us all if we go back. More than the one already blooming on your jaw there, my lady. More for all of us.”

She was silent.

“Begging your pardon,” said the driver. “I don’t mean to speak out of turn, of course. It’s only, in some ways, we are all in the same position with his lordship, are we not?”

“Perhaps,” she murmured.

“I have been in his lordship’s service for three years now, and I can guarantee it, we’d all rather we give up a few baubles and some of the provisions on board than go back to whatever punishment he has in store for us,” said the driver. “Everyone in this carriage was looking forward to a bit of time away from that man’s fists and whips, you most of all, my lady, I think.”

Isabella’s eyes were quite wide and round. “If you are with child, like you said, if you are, and if you have hopes of keeping that child from being dislodged from your belly—”

“Thank you, Isabella,” said Patience. Yes, she could see that if she ordered the carriage to turn round and go back to her husband, he would be furious. They’d all face the consequences, and it would be not only her own pain that she would be responsible for, but the pain of these servants. They depended upon her to protect them.

On the other hand, she couldn’t think her husband would be pleased to find they’d been robbed on the road either. But if she gave up her own personal things, her jewels and her necklaces, well, maybe he’d never even notice.

“It may be that there will be no one at the crossroads anyway,” she said in a faint voice.

“Quite right, my lady,” said the driver. “We may get through it with no difficulty. I’m for taking the risk, for what it’s worth, but I’m here to do your bidding. Say the word, and I shall carry it out, whatever it may be.”

Patience wasn’t used to having anyone do her bidding. Perhaps, little things, here and there, throughout her life, yes. She might have asked for a certain pudding to be made for her birthday or something like that, when she was a girl. She had looked forward to her Season as a time when she might have her heart’s desire—all manner of new dresses and her pick of eligible men. But then, Mark had lost all the money, so there was no Season, not truly. Before even the first balls were underway, Mark and Balley had been hashing out what Balley might give Mark to take her off his hands.

This was not the typical way of a marriage agreement. In a sense, a woman’s dowry was given from her family to her husband as a sort of reparation for taking over the financial responsibility of keeping her. However, it was customary for dowries to be held back for the use of a wife in the event of her husband’s death, all of that. So, dowries were a bit complicated in practice.

At any rate, it wasn’t done for a man to pay the bride’s family for the privilege of marrying her. Not usually.

It had been most irregular. Balley had wanted her badly. He’d signed over stocks in some company to Mark for her hand in marriage, had brought Mark in on some particularly lucrative investments.

At the time, she’d dared to hope that this meant that her situation might improve, if she was involved with a man who was so very deeply in love with her that he would pay dearly for her. But it had seemingly only raised Balley’s ire. By the time she was his, bought and paid for, he had felt as if he had already suffered so much for the privilege of possessing her that he’d been resentful from the get-go. He’d punished her for his own desire, she thought.

More than once, he’d said things to her about it, strange things, that she had tempted him on purpose, that she had bewitched him, that she had made a fool of him.

He hated her.

He certainly never had put her in a position where it was her bidding that was done.

If she had ever thought she wished for the responsibility of it, she took it back now. She didn’t want to make this decision. She didn’t want it all to rest on her shoulders.

But it would look weak if she dithered or if she deferred to the driver. Truly, she would be well within her rights to scold him for being as free as he had, giving his own opinion.

She drew in a breath, clutched Dash even more tightly, and did her best to look regal. “Yes, then,” she said. “The crossroads.”

“Very good, my lady,” said the driver.

Patience and Isabella retreated into the carriage. They shut the door. They were jostled about as the carriage turned around and set off in the direction of the crossroads.

The next bit of the journey settled into Patience with a dread that built and built.

It was not so very far to the crossroads, not really, but it seemed to take a thousand years. She tried to busy herself. She thought of taking off her necklace or the bracelet around her wrist. But this seemed to her to make it too likely that the worst happened. Mustn’t she hope for the best, in the end?

She spoke to Dash, trying to make her voice comforting, but it rang shrill to her own ears.

Isabella, too, was nervous, gathering up handfuls of her own skirt and then letting them go.

It was interminable.

Patience kept looking out the window, but it got darker and darker, and she could not see anything. Her heart began to thud wildly and she felt ill, like she might cast up her accounts, and she wondered if she must ask the driver to stop so that she might be sick outside the carriage, for she could not bear the idea of saddling Isabella with cleaning it up.

Patience squeezed Dash so tightly he whined.

She loosened her grip.

They drove.

She began to think they must have passed it by now. She had not been able to tell through the windows, but surely, surely, they had already gotten through the crossroads, and surely, the danger was passed, and surely—

And then a shot rang out, loud and clear in the darkness, and the horses whinnied and the carriage reared to a stop.

Patience shut her eyes and shuddered.

Damnation, she thought.

And then she scolded herself, for that was not a ladylike word, not a ladylike word at all.

The words were muffled, but loud enough that she could hear them inside the carriage. “Stand and deliver!”

The response of the driver was too low for her to make out, but she heard that he was speaking.

“Whose carriage is this?” said the voice of the highwayman. She thought, incongruously, that his accent didn’t sound quite right. He sounded lowborn, of course, but there was something wrong with the way he spoke, something that jangled against some part of her brain in a way that she couldn’t reconcile. She puzzled over that for so long she missed whatever else was being said.

Suddenly, the door was being yanked open and a man stood there. He had on a domino mask and below that, his chin was covered in a dark shadow of hair, as if he hadn’t shaved recently. He wore a long black cloak and black clothes beneath.

She thought to herself that he looked like he belonged at a masquerade ball, that there was something foolish about his costume, something that didn’t quite add up either. She blinked at him, blinked hard.

“Why, look at that,” said the man. “It is the Viscountess of Balley herself, in the flesh. This is my lucky day, innit?”

The accent again. It wasn’t—it was put on. He didn’t naturally speak that way, and she was sure of it.

“Out, milady,” said the highwayman, his lips twisting into a satisfied smile under his domino mask. “You’re coming with me.”

She drew back, too stunned to react in any other way.

“Now, hold on, I can’t allow that,” said the driver, who had hopped down from the top of the carriage. “My lady, reach above you, please. There’s a gun there, and I know my master keeps it loaded—”

The driver stopped speaking because there was a blade at his throat.

“None of that,” said the highwayman, but he was looking at Patience. “Have you ever seen a man’s throat cut, milady?”

She was trembling, and she was clutching Dash too tightly again, and the little dog was wriggling, whining.

“Well?” said the highwayman. “Have you?”

“N-no,” she whispered, though she had once seen a chicken killed by the cook at one of her family’s country estates. The cook had lost her grip on it, and the chicken had gotten away, and it had half of its head still attached, and it was moving—

“Would you like to?” His put-on Cockney accent was too broad again. He laughed, grinning at her while his eyes glinted in that domino mask of his.

The driver whispered, “You cannot take the viscountess. My master will kill me if I allow that. So, if you think to threaten me with my life now, know it comes to the same thing either way. I cannot permit that.”

“Right, well, I’ll cut you elsewhere if you like, enough to make it look like you tried,” said the highwayman, still grinning at Patience. “Let’s go, milady, out of the carriage.”

She licked her lips. “But why? Don’t you want my…” She touched her necklace. “I can hand that to you without getting out.”

“No, no, milady,” said the highwayman, chuckling. “Let me explain this to you. I’ll speak slowly, because you seem a bit confused and upset, which is natural, really, given the situation. I. Am. Kidnapping. You.”

She let out a gasp.

“Out,” he said.

“No!” she said, retreating into the carriage.

The highwayman groaned. He moved fast, lightning fast, and he threw his blade to another hand and hooked his arm around the driver’s neck. He squeezed, and the driver crumpled to the ground. The highwayman put the knife in his teeth and bent down, taking a length of rope from somewhere within his cloak. He began to tie up the driver, and as he did this, he talked around the knife between his teeth, which had the effect of making him lose his put-on accent entirely. “You see, viscountess, everyone knows how much good old Balley went through to get you in the first place, so it only stands to reason he’ll pay dearly to get you back. Get out of the carriage.” Finished with his work, he set a foot on the driver’s back. He took the knife out of his mouth. “Don’t worry about him. He’ll wake up in a moment or two. It’s a point on the neck. Put pressure on it, light’s out.” Now, his accent was back. “Come on, then.” He beckoned to her, but with the hand holding the knife.

She shied away.

He looked at the knife, shrugged, and put it into a scabbard hanging on his belt. “Leave the dog.” He beckoned again.

“He won’t pay for me,” she said in a tiny little voice.

“Oh, certainly he will,” said the highwayman. “It was all over town, the way he went after you. He’s obsessed, and this is the luckiest break my boys and I have had in some time.”

Boys . She looked out into the darkness. Were the other Lords of the Crossroads out there, waiting to step in?

“Yes, they’re waiting for a whistle,” said the highwayman. “If they arrive, though, everyone bleeds. You don’t wish that, do you?” He beckoned again.

Even if she had wanted to obey this man, she couldn’t. She couldn’t move.

Isabella let out a very tiny little noise of fear.

It galvanized her. Patience reached forward and made to shut the carriage door.

Except the highwayman stopped her.

And then he was half inside the carriage, and he reached out with one hand and scooped up Dash. He held the dog by the scruff of its neck and dangled it in front of her.

“Don’t hurt him!” she shrieked, lurching forward, arms out for the dog.

The highwayman backed up.

Below him, on the ground, the driver was awake and struggling. He was tied at the hands and feet and he couldn’t stand.

She tumbled out of the carriage and snatched up Dash, pulling the little dog into her arms. Dash barked at the highwayman. He snarled.

The highwayman laughed. “There we are.” He seized her by the arm and began to pull on her. “Leave the dog.”

“Let go of me,” she said in a low, low voice.

“Leave the dog,” he repeated.

And in that moment, she recognized him. Well, sort of. She didn’t know his name, but she had seen him before, when she was a guest at a house in the country—she couldn’t remember which house or where or when, or anything like that, but she had seen this man before, and he was no highwayman, he was…

A lord.

They were called Lords of the Crossroads. She sputtered at the sheer cheek of it. How dare they?

He tugged on her and she was too stunned by the revelation to struggle. She came along with him.

He tried to take Dash now, but Dash snapped at his fingers, and the highwayman pulled his fingers back. “Fine, keep the dog,” he muttered. He pulled on her, pulled her off into the darkness.

She looked over her shoulder at the carriage.

“Isabella, untie me!” shouted the driver.

But Isabella was frozen inside, unable to move, her eyes wide and frightened, still making tiny, scared noises, and she didn’t do a thing.

Patience stared at the carriage, stared as she allowed herself to be led away, as her traitorous feet moved, until the darkness swallowed them all up, and the highwayman yanked her around a tree trunk and then another tree trunk and she found herself in some wooded area.

Should have fought, she thought. Why didn’t I fight?