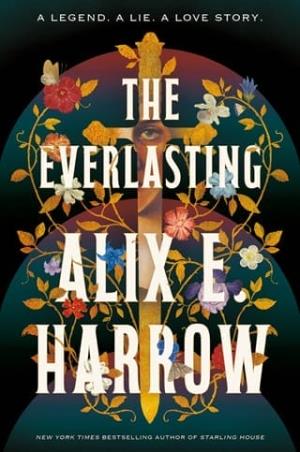

The Everlasting

The Everlasting

UNA AND THE YEW

It begins where it ends: beneath the yew tree.

The yew stands in the wood like a great queen grown old, limbs wracked with age, head bowed by the weight of her crown.

In the gnarled grain of her trunk there is a woman’s face, with weeping cankers for eyes, and in her heartwood there is a sword driven so deep that only the hilt is still visible.

You already know the name of that sword, I think; who doesn’t?

They say time runs strangely, beneath the yew. They say many things are lost there, among the tangled roots: years, hearts, lives. But they say, too, that some things are found: fates and fortunes, beginnings and endings.

And, once, a child. You know her name, too, or at least one of them.

She was still pink and toothless when the woodcutter found her, and he fretted. He needn’t have; she grew quickly and well, as wild things do.

As a child she was all mischief, her fingertips stained with yewberries, her hair light and fey as dandelion down. As a girl she turned solemn, studying the woods as a saint would study the word. From them, she learned everything.

She learned to run as the stag runs and to be still as the goshawk is still; to stalk and to swim, to wrestle and to whistle; to vanish so thoroughly her own father could not find her and to kill so cleanly she left nothing but a tuft of fur, the metal scent of entrails.

She was strong, and arrogant in her strength. She was a young lion, a child-king, a lord of the wild woods.

And yet, she was no one at all. She was nothing, daughter of nothing, heir to nothing.

Just another of the numberless, featureless small folk of Dominion, whose name would not be forgotten only because no one ever learned it in the first place.

She would die a heathen death, unchristened and unshriven, so that even God would not remember her.

But then came her twelfth winter, and the Brigand Prince.

She was away when it happened. Perhaps she was stealing feathers for her fletching or pulling the hide from a hare. What matters is that she was far enough from her father’s cottage that she did not hear the ring of iron-shod hooves, or the screams.

When she returned to the cottage the fire was cold, and her father was dead.

They had taken everything—the sow, the salt box, the pair of axes her father kept above the hearth—so she went to the yew.

She wrapped her hands around the hilt of the sword that had waited there for so long that the bark had boiled and knotted around the blade.

There were whispers about that sword, even then, but she hadn’t heard them.

She hadn’t heard the tales of an ancient blade that neither dulled nor shattered nor rusted but remained whole and shining.

She hadn’t heard the prophecy that said it would be drawn only in the country’s darkest hour, by her rightwise champion.

She only knew that her father was dead, and that the hilt in her hand felt like the clasp of an old friend.

And so—full of grief and fresh-born fury—she drew the sword from the yew.

She overtook the Brigand Prince and his men that very night, tracking them through new-fallen snow, and found them while they sat sated and dozing around their fire, beards shining with pig fat.

She might have slit their throats in silence—she had learned to be silent as the fox is silent—but she was arrogant, and she was angry, so she called out to them first. She allowed them to scrabble blades from sheaths, spears from saddles.

And then she fell among them: a wolf now, a shrike, a terrible reaping.

When she was through, and the woods were quiet, the snow was no longer white.

That is how the queen—who was not yet the queen but only a king’s daughter taken captive by the Brigand Prince—first saw her: a wet, red girl in the center of a wet, red circle, her wrists bent beneath the weight of a blade that had not been borne in a hundred years and a hundred more.

The queen-who-was-not-yet-queen rose and went to her, and the girl trembled, because the woman was so beautiful and gentle, and because the girl had killed those men so easily, almost joyfully. Her own body felt sharp and unwieldy, like a knife without a hilt.

The queen asked, ‘Who are you?’

And the girl answered, ‘No one.’

The queen asked, ‘To whom do you belong?’

And the girl answered, with grief, ‘No one.’

The queen knelt low. She stroked the girl’s hair, heedless of the stain it left on her palm, and the girl felt her terror washed away beneath that touch. She thought she would not mind being a knife, so long as it was this hand that wielded her.

‘Then,’ said the queen-who-was-not-yet-queen, ‘will you be mine?’

‘Yes,’ the girl whispered, and meant it with all her young and shattered heart.

So the woman—who would be queen very soon, for what is a queen but an ambition pursued—took the sword from the girl’s hand and bid her kneel.

She asked the girl if she would swear by her good right arm, and by her left, and by her life and death to serve no master save her queen, and she touched the blade once to each of the girl’s shoulders and to the back of her bowed head.

The girl said, three times, ‘I swear it.’

‘Then rise, Sir Una,’ said the queen, because the name meant only, and already she could tell there would never be another like her.

Over the years Una gathered more names. She became the Queen’s Champion, the Red Knight, the Virgin Saint, the Drawn Blade of Dominion. She became Sir Una Everlasting, hero and paragon, arcing through history like a bright-tailed comet.

She became a legend.

Most legends are lies, pretty stories meant to keep the children quiet on long winter evenings. But I, who rode so many miles at her side and slept so many nights at her feet—I, who was her shadow while she lived and her echo ever after—am no liar.

I will not waste too much time with those stories that have already been told and retold, traded like coins in every hall and tavern.

Everyone has heard the tale of Una and the False Kings, and the Winning of the Crown, and the First Crusade, which brought all of Dominion into the light of the Savior.

Everyone knows how her legend began, beneath the yew.

But gather close, all true hearts of Dominion—

And I will tell you how it ends.

—Excerpted from The Death of Una Everlasting, translated by Owen Mallory