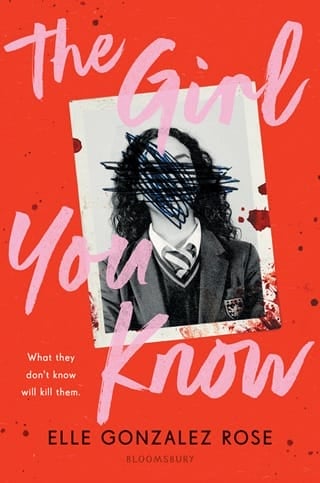

The Girl You Know

Chapter One

CHAPTER ONE

The bitch at table three is going to ask me for something again. I can see it in the quirk of her mouth, the twitch of her manicured nails against the counter. Her hand goes high in the air, snapping her fingers like a whip before I can pretend I didn’t see her.

“Miss? Excuse me?”

It’s accusatory. She’s already found me guilty of whatever crime she’s made up. Her thin lips pinch into an even thinner line, her red lipstick disappearing into her mouth. Turning around and walking back into the kitchen would just dig me deeper into my grave. I kissed my tip goodbye when she first called me over, complaining that her coffee was lukewarm. People with complaints five minutes into a meal don’t stop at one. They’re full of them. Bitching and whining like windup toys until you offer them a slice of pie on the house to shut them up.

The woman bristles when I step up to her, tucking a dishrag into the belt of my apron. She takes her precious time, straightening out her collar and the gold-plated necklace at the base of her throat. “Joan,” spelled out in gold and adorned with pearls.

“I ordered my eggs over easy.” She waves her finger over the plate with such disdain you’d think I served her microwaved roadkill. “This,” she sneers as she pokes one of the eggs with her fork, a river of yolk trailing down to her home fries, “is over medium .”

I think of her then. Solina.

They’d cleaned up most of the blood by the time I was escorted down to the dingy, poorly lit morgue, which was half the size of the hospital itself. You don’t need much space for anything in a town like Luster. Latest census has our population in the high four figures. We’ll all die someday, though, and they’ll always need a place to store us.

The slab they laid her on seemed too clean. Guess that says something about the dishes we eat off. When they folded the white sheet back at her collarbone, her head tilted. A trail of blood, black as her hair and the grime beneath her fingernails, dribbled down her chin, staining that too-clean slab. I can smell it—the rot, the salt of the river turned putrid and vile—as yolk drips down the tines of Joan’s fork. My stomach lurches when a drop falls onto the counter.

When will I forget the smell?

“Are you listening?” My hand flies up to my mouth as Joan snaps her fingers again, this time in front of my face. If my body weren’t used to pushing things down, I’d have already hurled all over her crisp white blouse and over-medium eggs. “I’d like to speak to your manager.”

That’s enough of a threat to force my stomach into submission. I swallow the bile down and slap on the customer service smile I’ve spent three years practicing, but never perfecting.

“Of course, so sorry about that.” I clear her plate before she can see the way my hands tremble. She turns back to her newspaper with a huff, muttering something under her breath about Podunk towns.

Over a week and it still hasn’t sunk in. That the world has to go on. Shifts still have to get covered, coffee still needs to be poured, and strangers will still come in and out of this shabby diner on their way to someplace better. Strangers who don’t know that my sister is dead. Who don’t care about anything other than how their eggs are cooked.

“Table three wants to talk to you,” I mumble as I slam my way into the kitchen.

Dede looks up from the grill when I toss the rejected eggs down behind him. “Watch it,” he warns, wiping the sweat off his brow with a rag before squinting at the plate. “What’s wrong with it?”

“Over medium.” Like Joan, I dip a clean fork into one of the eggs, breaking the yolk free. “She wanted over easy.”

“Puta mierda,” he grumbles, throwing his sweat rag onto the plate. “You serious? That shit’s over easy, yo.” He pushes the rag aside to run a finger through the stream on the plate. “Look at that.” Yolk trickles down his fingers onto the A and I of his FAITH knuckle tattoo. He wipes his hand off before my stomach can twist again.

“You wanna argue with her, be my guest.” I scrape the plate off into the trash. A perfectly good meal, dumped out with the burnt hamburger meat and browned lettuce.

Dede starts up a fresh string of profanities, alternating from English to Spanish to the handful of Arabic he learned from the night shift busboy. He scrubs the kitchen grime off his hands before heading out to the floor. I’m sure he’s not what Joan expects of a manager, reinforcing whatever preinstalled, probably racist ideas about Podunk towns she had when she decided to stop in Luster.

I keep myself busy while Dede’s gone—chopping lettuce, unpacking boxes, scraping crusted food off supposedly clean plates. Letting my mind wander always brings me back to Solina. Her on that slab, or those pictures the cops tossed down in front of me like playing cards. Twisted bones and ripped skin. The cops hadn’t even blinked. Broken bodies are par for the course. My sister was just another box on their to-do list.

Keeping busy keeps me sane.

Times like these make me wish I’d let Solina talk me into getting a better phone. At least then I’d be able to listen to music. Instead, I’d played it practical. My phone came in a hard-plastic package from the back of a Walmart two towns over. The kind that’s usually reserved for drug dealers and businessmen’s mistresses. No frills, just a way to make and receive calls. Technically I can text, but I don’t have the patience for the keypad. Or the time to spend five minutes thumbing one key just to type the letter C .

Solina hated that I didn’t respond to her texts. I always told her to call me if she needed to talk that bad. Sometimes she did. Most of the time she didn’t. Her sophomore year she’d send me a text every morning. Good morning my sweet gremlin sister or This bird’s been sitting outside my window for the past twenty minutes. Do you think it’s spying on me? I would roll my eyes and delete or ignore her. One time I took a whole twenty minutes to finally respond, warning her that I’d block her if she kept sending me pictures of her breakfast.

Shit .

The tears come quick as a tidal wave, cresting as my chest tightens and washing over me with each exhale. Holding it in burns all over. My eyes, my chest, my fingers digging into the steel counters. I can’t do this. Not here, not now. Ten days since they found her and I haven’t let myself sit with it yet, feel all that pain sitting in the pit of my stomach like the food I struggle to keep down. If I do, I don’t think I’d come back. That much hate and rage and sadness can change a person. If you’re from a family like ours, it’ll destroy you. Papi lost someone he loved, holding Mami’s hand the day she died. He sat in his pain for months, leaving me and Solina to fend for ourselves until he would hopefully pull himself back together again. He’d fought this battle once, after he “fell in with the wrong crowd” in high school, and won. He was six years sober when he met Mami, ten when they had us. He could do it again.

But he didn’t. And look where we are now.

“Goddamn trippers,” Dede grumbles as he reenters the kitchen. “Always looking for free shit.” It’s no surprise that Joan is an out-of-towner—better known to us unfortunate townies as trippers. Luster’s full of them. We’d have a higher population if you counted the hundred or so people who come through every day, driving off to somewhere more exciting. Up to the Canadian border, or down to Spokane. We’re the unfortunate souls stuck in the middle. It’s even the official Luster motto, printed in chipped script on the road sign when you first get into town.

Luster: Halfway to Something Great.

Dede sags against the counter, hand stalling as he reaches for a bag of frozen patties. “You good?”

I nod, not trusting my voice to keep up with the lie.

“Lu.” Dede’s voice is quieter as he shifts closer toward me. He smells like sweat, grease, and tacky cologne. “I know you’re not the, uh … talkin’ type.” That’s the understatement of the century. We’ve gone days without saying anything other than “Hello,” “Goodbye,” and “Burger special for table two” to each other. “But you know you can talk about it. If you want.”

The offer is familiar. Cops and nurses and old-acquaintances-turned-strangers prodding me to open up to them because they don’t know what else to say when the unimaginable happens. This one hurts the most, though. Hearing the sad twinge in Dede’s voice, the multiple sentences without any cursing. A stark reminder that things are different now, that people will treat me differently.

I can’t blame him for trying. As all-consuming as this feels, I’m not the only one who lost Solina. She’d sit at the counter every summer, legs tucked under her and books scattered everywhere, taking up more space than one person should. Dede would bring her enough Diet Cokes to keep her fingers sticky all summer long. Sometimes he’d bring her a grilled cheese if she stuck around until after the lunch rush. Crusts cut off. Tomato slices on the side.

She was picky like that. Even when I reminded her we didn’t have picky-people money. He let her get away with it, though. Encouraged it, even.

“Gotta respect a woman who knows what she wants,” he said, rewarding her with a high five and a plate of fries.

Telling him she was gone was the only time I’d seen him cry. Not the day he dropped a box of potatoes on his toe, or when he spilled hot oil on his arm. Not when his first wife left him, or when the second one dumped him for his stepbrother. He’d helped me drive through town the morning I realized she was missing, calling out her name for hours as we drove down the handful of roads that make up Luster. He was there when we got the call too. That they’d found a body in a place we never considered looking. As much as I’d wanted to curl up beside him then, I didn’t. Didn’t cry either. I held him instead, let him sob into my shoulder while I told myself that Solina had moved on to a world that deserved her. One of us had to stay strong.

That’s one thing that hasn’t changed since Solina died. I’m still the one who has to be strong.

“Thanks.” I give Dede a tight-lipped smile. I’m sure he doesn’t believe it, but he doesn’t push me.

He sighs, running a hand down his stubbled chin and glancing over at the clock. “You’ve busted your ass enough for one day.” He turns back to the grill. “Head home.”

I glance down at my watch. Half the time it’s broken, but even if it was running slow, I’d still have another hour left of my shift. “You sure?”

He nods, pointing his spatula at the nearly empty dining area. Snow always makes for a slow day. Storm season kills. Three weeks out of the year, I stomp home soaked down to my underwear with barely a quarter of my usual tips. “Unless you want to stick around,” he teases with a raised brow.

With Joan? No way.

I toss my apron into the cubby beneath the cutting boards, along with my worn-down sneakers, lacing up my snow boots while Dede gets back to flipping burgers. There’s a Styrofoam box with my name on it sitting on the counter when I stand back up. My usual order: a burger and fries. Simple and easy to find in tough situations. Unlike my sister, I follow my own advice.

“Thanks again,” I say as I open up the box to steal a fry.

He doesn’t bother to look up from the grill, grunting as he points his spatula at the door this time. “Get outta here before I find something for you to do.”

I don’t need to be told twice. Carefully tucking the box into my backpack, I give Dede a wave and a goodbye muffled around a mouthful of fries as I back out the kitchen door. Joan’s seat is empty. She must’ve decided to skip out on a new platter of eggs, and the check, apparently. No surprise, not a tip in sight. Not even some loose change from the bottom of her purse.

The seat beside hers is now occupied by a different kind of nuisance—Luster’s resident evangelical savior and bane of Dede’s existence, Todd Lowry.

“Luna!” he shouts before I can turn back around and escape through the back door. “I’ve been meaning to track you down.”

The sound of his voice makes me freeze. Todd is usually impossible to shake off, but Solina always managed to do it with grace. On instinct, I turn to look for her. Wait for her hand to slide into mine and pull me toward the door as she brushes past Todd with a smile and a wave. She could talk her way out of anything, with her soft voice and kind eyes, while I glowered and waited for her to whisk me to safety.

Now there’s no one left to fight the battles for me.

In Todd’s rush to get over to me, the trusty postcards he shoves at every tripper he can find—promising salvation to those who seek it—fly out of his hands and skitter across the floor. Hundreds of neon-yellow-and-green eyes peer up at me as he scrambles to pick them up off the freshly mopped tile. Unblinking and judgmental as hell.

IT’S NOT TOO LATE TO SAVE YOUR SOUL

Beneath Todd’s ominous promise is a phone number, punctuated by hands folded in prayer. A number Solina and I once called just for the hell of it, only to find out it leads to a disconnected line. So much for saving your soul.

It’s not the first, or even hundredth, time I’ve seen Todd’s postcards, and yet something new lodges itself in the pit of my stomach. Something so wicked I don’t dare dwell on it.

“I—uh—gotta …” I don’t finish that thought, turning on my heels and making a break for the bathroom at the opposite end of the room. Todd calls out to me but doesn’t bother following. I’ve spotted him dozens of times since the news about Solina broke. It’s impossible not to run into someone like Todd in a town this small, preaching the Lord’s word anywhere there’s a soul to be saved.

People like him prey on the weak. The homeless, the hungry, the down-on-their-luck looking for something to believe in. It’s obvious what he wants every time he’s tried to corner me since the news about Solina spread like wildfire. A chance to make a broken girl whole again.

I shoot Dede a text once I’ve locked the bathroom door. Give it a few minutes and he’ll have chased Todd off with some choice cusses and a threatening crack of his dish towel. We hardly care about our image, but stragglers like Todd are as annoying for us as they are bad for business.

The storm rages on while I camp out on the closed toilet lid. I still haven’t heard back from my roommate, Tiffany, about a ride home. Hopefully she can duck out of work early too. If a diner’s this slow in a snowstorm, you’d think the local library would be completely dead.

While I wait for her to respond, I pull my hair free from its messy bun, hiding the baby hairs that managed to spring free. Even in the dead of winter, the diner manages to stay humid, the kitchen sweltering like a deep-fried jungle.

Solina hated our hair, and I couldn’t blame her. A single drop of moisture and all hell breaks loose. The summer she sweet-talked me into buying a flat iron, she’d sit in our room for hours, pinching, pulling, and lathering her hair with oils whose names I couldn’t pronounce until it was as pin straight as the model’s on the box. I admired her patience, even when the stink of burnt hair lingered for weeks.

When Mami was still alive, she’d always say she was blessed to have two daughters, beautiful in all the same ways. The same round cheeks that we hoped would go away once we were older, but never did. The same lips, soft pink and curved at the center. The same eyes, dark brown with even darker lashes. Hers wide, mine sunken. Even the same freckles, dotting the corners of our eyes and apples of our cheeks like stars.

Mami said we were blessed too. To be able to look at your sister and see so much of yourself. The world knew we would have a special bond from the day we were born. People expect that from twins, especially identical. We didn’t come up with secret languages or codes like all the books said we would. No one could have prepared us for the bond we’d have.

Looking up at the mirror, seeing the same cheeks and lips and eyes that I saw on that slab—mottled and gray and drained of everything that made Solina who she was—it doesn’t feel like a blessing.

It feels like a curse.