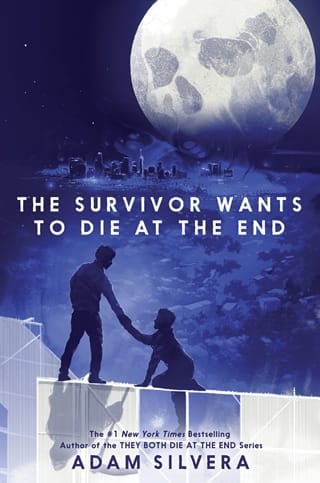

The Survivor Wants to Die at the End (They Both Die at the End #3)

Los Angeles Paz Dario

Los Angeles July 22, 2020

Paz Dario

7:44 a.m. (Pacific Daylight Time)

Death-Cast never calls to tell me I’m gonna die. I wish they would.

Every night between midnight and 3:00 a.m. when the heralds are alerting people about their End Days, I stay up and stare

at my phone, willing it to ring with those haunting bells that will signal my early death. Or my late death if we’re being

real about how little I’ve wanted to be alive. I dream of the night when I can interrupt my herald’s condolences over how

I’m about to die and just say, “Thank you for the best news of my life.”

And then, somehow, I will finally die.

My phone didn’t ring last night, so I’m forced to live through another Not-End Day.

I’m always performing a will to live for all the people working hard to keep me alive: my mom, obviously; my stepdad, who used to be a guidance counselor and still acts like one; my therapist, who I lie to every Friday afternoon; and my psychiatrist, who prescribes the antidepressants I overdosed on in March. I almost feel guilty wasting everyone’s time since I’m a lost cause. But if I can’t convince everyone that I only tried killing myself because of that documentary about my childhood incident, then I’ll be sent to a suicide treatment facility where I’ll not only have even more people working to keep me alive, I won’t stand any chance at trying to kill myself again.

If this Not-End Day goes as well as I hope, I might be happy to stick around.

For the first time in almost ten years, I have a callback. And not just any callback but a chemistry test to be the love interest

in the movie. And not just any movie but the adaptation of my favorite fantasy novel, Golden Heart . All it took was one killer self-tape and lying about who I am.

Now I gotta go book my dream role.

I’m pacing my bedroom, going over the audition sides, even though I’ve got these lines down. Everything in here is black and

white except for the novels, plays, and video games that entertain me on my Not-End Days. Mom got me this big Zebra plant,

which, despite the name, doesn’t match my room’s vibe. It was a nice thought to get a natural pop of green in here, but I’ve

had a hard enough time nourishing myself, so the plant has browned from neglect; I gotta throw it out because I can’t watch

a plant die before me.

Okay, it’s time to get ready. I tuck my audition sides into my hardcover of Golden Heart as a 912-page good-luck charm and then stuff it into the backpack I usually use for hiking. I grab the black T-shirt and jeans requested by casting, and I’m about to hit the shower when I notice my 365-day journal on the floor. I’m quick to throw it back in my nightstand, since I forgot to do so around 3:00 a.m.; I can’t have anyone looking in there.

I crack open my door, hearing a Spanish song playing from the old radio I moved to the top of the fridge after we got rid

of all the alcohol. Mom and Rolando are laughing as they cook breakfast before she goes to work at this local women’s shelter.

It’s the little moments like this when Mom isn’t bringing me plants or supervising my antidepressant dosage that give me hope

that she will actually be okay if I die. Even if she said otherwise after my suicide attempt—I’m only talking about the one

in March, since no one knows about the second.

Before I put on a show as Happy Paz for Mom and Rolando, I have to get ready, just like any actor who goes through hair and

makeup. I’ve only ever been on one movie set, back when I was six, but I remember thinking how cool it was to have artists

help me get into character before a director calls, “Action.” Now I do all of this by myself before performing happiness.

I rush down the hall and into the bathroom that’s still warm and misty from Rolando’s morning shower. I wipe the steamy mirror,

trying to see the villain everyone else sees, but I only see a boy who has dyed his dark hair blond to book this job and who

is growing out his curls to hide the face everyone knows more from the docuseries about the first End Day instead of his small

but once promising role in the last Scorpius Hawthorne film.

The cold water of the shower shocks me awake before I twist the knob so far that the hot water turns my tanned skin red. I force myself to stand there even though my body wants to take control of my legs and back away. The body eventually wins, and I get out.

The sink is cluttered with all of Mom’s and Rolando’s things, like her brush with a forest of black and white hairs, his comb

and gel, the cactus soap they picked up from the Melrose Market, and the porcelain plate where she leaves her engagement ring

when she’s going through her moisturizing routine. No real sign of my existence except for the toothbrush inside the orange

plastic cup with theirs. That’s on purpose. When I’m dead, I want Mom to forget about me for as long as possible. That means

not seeing my things around our shared spaces. If Mom’s haunted by my death, she’ll be forced to move again to escape my ghost

like we did after Dad’s death, but this tiny house that Mom and Rolando bought together is her favorite part about living

in Los Angeles. It represents our fresh start.

What was supposed to be our fresh start, at least.

In addition to a suicide note for Mom, I should leave another for Rolando to set up a Graveyard Sale because I know Mom won’t

have the heart to sell my things herself. She’s the breadwinner of the house, but barely; we’re talking stale, week-old bread

breadwinner. They can probably make a few thousand by selling my copy of the last Scorpius Hawthorne book that was signed

by the author as well as the Polaroids she took of me with the cast.

That trip to Brazil with Mom to film my scene was mind-blowing, I still can’t believe I got to visit the iconic set of the

Milagro Castle and—

Nope, no going down memory lane for my time as young Larkin Cano when I have a different role to play now. Not the one for the audition. The role I play every Not-End Day.

Fully dressed and clean, I grab the doorknob and whisper, “Action.”

I become Happy Paz.

“Good morning,” I say with an Oscar-winning smile as I enter the living room.

Mom and Rolando are eating breakfast tacos in our dining nook and playing Othello, the board game I used to love as a kid.

They look up with genuine smiles because Happy Mom and Happy Rolando aren’t roles they’re playing.

“Morning, Pazito,” Mom says.

Being called Pazito is something else I used to love as a kid.

“You ready for your audition?” she asks.

“Yup.”

Rolando fixes me a plate. “Eat up, Paz-Man. You’ll need your strength.”

I force-feed myself because they’ll get suspicious if I don’t eat. The truth is that while I don’t usually have an appetite

for food, I’m always starving for life. Sometimes I feel so empty that my stomach aches, like it’s growling for happiness,

but there’s never anything to eat or nothing looks good or when I’m finally in the mood for something it feels like no one

wants to take my order.

“Would you like help running lines?” Rolando asks.

I pass because when I originally filmed my self-tape, Rolando was my reader, and he was way too dramatic, like he was auditioning for some telenovela from behind the camera. I had to kick him out and prerecord the other character’s lines in a deeper voice, filling in the silent spaces I reserved for my character. That performance got me this callback. I don’t want Rolando getting in my head again.

“How about a ride to the audition?” Rolando asks, always desperate to show that he’s different than my dad, which yeah, I

know.

“I’m gonna walk. I want the fresh air.”

He holds his hands up in surrender. “I’m taking the day off if you change your mind.”

“Don’t you need a job to take the day off?” I fake a laugh so it sounds like a joke, but Mom scolds me anyway while Rolando

laughs too. His laugh is also fake.

“I am taking the day off from hunting for a job,” Rolando says while brewing tea and talking about the work he’s gonna do

around the house.

I zone out.

Last month Rolando got laid off at this local college because of funding. It sucks because he loved having an office job again,

especially after homeschooling me for most of high school, but the mounting mortgage and medical bills suck even more. He’s

being precious about the next job he takes. “Nothing that gets me emotionally involved,” he keeps saying.

The career adviser gig was perfect because it was just a job talking about other jobs while also scratching his itch to help people. Unlike his draining years as an elementary school guidance counselor. “Who knew children could have such troubles?” he has said more than once, even around me, someone who faced a lot of troubles as a child. And then of course there was his most short-lived but taxing job as one of the world’s first Death-Cast heralds. It’s been almost ten years since he quit on the first End Day. The same day that changed my life so quickly that I became that child with a lot of troubles.

It’s gonna be wild if I book this movie before he gets a job.

Rolando brings Mom tea and a kiss. “Enjoy, Glorious Gloria.”

“Thank you, mi amor.”

I’m so happy Mom is in love—true love this time—but sometimes it’s hard to watch, knowing that I’m gonna die without being

loved. Every night when I’m in bed alone, hoping that Death-Cast calls, I wonder if I would start to fear for my life if I

had someone next to me. Someone holding me. Someone kissing me. Someone loving me.

But who would ever fall in love with a killer?

No one, that’s who.

I go clean my dish, letting hot water burn me again. I switch off the faucet before anyone can notice my hands are cleaner

than the plate.

“Pazito?”

“Yeah, Mom?”

“I asked if you’re okay.”

To be a great actor, you have to be a great listener, but I was so in my head just now that I didn’t hear my scene partner. Now I’m staring like I’ve forgotten my lines. I’m falling out of character, like my Happy Paz mask and wardrobe’s threads are being pulled off of me, exposing me as a nonworking actor who doesn’t even deserve to work. No, I’m a great actor, and yeah, great actors have to be great listeners, but they also have to act truthfully. So I’m gonna tell the truth—well, a truth.

“Sorry, Mom, I’m just on edge over this audition,” I say while staring at the floor, like I’m embarrassed. That part might

be an act, but I’m selling the truth that, yeah, my mood is off, but check me out, I’m talking instead of hiding everything

like last time. Then I top it off with a lie: “I’m okay.”

The legs of Mom’s chair begin screeching and then halt. She’s desperate to comfort me, but I’ve told her that I need some

space whenever I express myself because all the hovering makes every little thing feel much bigger than it is. I used all

the right words from my therapist to get that across, and it’s working, but I know how hard it is for Mom to not be able to

mother me.

It’s hard for me too. If only a hug could save me.

“The best thing you can do at this audition is be yourself,” Mom says.

“Doesn’t he have to be a character?” Rolando asks.

“He has to bring the character to life, like only he can,” Mom says. She’s been this encouraging of my dreams ever since I

was a kid. “Go make this callback your comeback, Pazito.”

“I will,” I say.

The stakes have never been higher. If I don’t book this role, I won’t have anything to live for.

I start heading out when Mom calls after me.

“Let me grab your...” Her voice fades as she goes into her bedroom.

I already know she’s getting my daily antidepressant. The bottle with my Prozac is hidden somewhere in her room because I can’t be trusted to respect my dosage after the first time I tried killing myself.

I had my reasons.

In early January, Piction+ started streaming their limited docuseries Grim Missed Calls about the Death’s Dozen, the twelve Deckers who died on the first End Day without warning due to some mysterious error with

Death-Cast’s equally mysterious predictive system. The episodes aired weekly, each revolving around a different Decker. The

finale was about my dad, who didn’t believe in Death-Cast. The filmmakers wanted to include us, but Mom declined and begged

them not to move forward with this project because it would reopen a terrible wound (as if it ever really closed). Her pleas

were ignored because “history needs to be remembered.” It wasn’t surprising when we found out the filmmakers were pro-naturalists,

people who wish to preserve the natural ways we have always lived and died before Death-Cast. That docuseries was never about

remembering history. It was a hit-piece against Death-Cast. And I got caught in the cross fire.

As if my anxiety wasn’t sky-high enough as we counted down to the finale’s premiere, the episode aired during the same week the government issued that stay-at-home order to prevent the spread of the coronavirus, guaranteeing that everyone would have nothing to do but freak out and watch TV. It was suffocating watching that press conference with the CDC and Death-Cast where they projected that over three million people could die worldwide if we didn’t do our part immediately by staying indoors, and the docuseries only made that worse for everyone by casting doubt in Death-Cast because of their forgotten fatal error almost ten years ago.

No matter what happened—pandemic or no pandemic—my world was always gonna become more unlivable after the finale aired. I

never watched, but the filmmakers apparently sensationalized my traumatic childhood incident and the trial that followed,

portraying me as nothing but a psychotic hit man groomed by Mom so she could continue her affair with Rolando. And millions

believed this.

So, on the fourth day of sheltering in place, an hour after the Death-Cast calls ended, I tried proving Death-Cast wrong by

swallowing my entire bottle of antidepressants and washing it down with my stepdad’s bourbon.

Then I waited to die, which is becoming the story of my life.

My vision got hazy, I started burning with a fever, and I began passing out, shocked that I was finally dying. I was too weak

and drugged and drunk and near death to cry over how much it sucked that I’d reached this dark place, but also happy I was

getting out for good. I would’ve died if Mom hadn’t woken up from her usual nightmare about Dad, only to find something worse:

me unconscious in a puddle of my vomit.

To this day I don’t remember falling out of my bed or the ambulance ride or my stomach getting pumped, but I’m still haunted by waking up in the emergency room, handcuffed to the bed’s rails like I was the dangerous criminal the docuseries made me out to be, and my mom removing her surgical mask as she begged me to never do anything like that ever again.

“I’m a planner,” Mom had said through tears, gripping my hand. “But I will not plan to live in a world without you, Pazito.

If you take your life, then I will plan to take mine too.”

I spent three days in the psych ward thinking about what Mom said. I love her so much, but I hate that threat about killing

herself too if I die by suicide. She has so much to live for, even if she’ll no longer be a mom because her only child will

be dead.

I can’t handle this pressure to keep living when I have nothing to live for.

I need to live my life—and my death—how I see fit.

I’ve been biding my time because I learned my lessons about trying to prove Death-Cast wrong. There was that suicide attempt

in March, but the one from my birthday last month has to stay a secret or I won’t get the chance to try again in ten days

on the ten-year anniversary of my dad’s death.

Mom comes down the hall and gives me one pill.

I swallow my Prozac and smile like it’s already anti’d all my depression.

Then Mom keeps staring, almost like she’s a casting director who isn’t buying my performance as Happy Paz and is only seeing an actor overacting, which is the last thing any respectable actor wants. But that’s not it. She sees me as her baby, her only child, the kid she once accompanied to auditions, the kid who she tickled during Halloween costume fittings, the kid who used to believe in prophecies because he used to believe in the future.

The kid who thought he was being a hero when he saved her life.

The kid who grew up and now wants to die.

“I hope you feel better, Pazito.”

“Me too, Mom.” I’m telling the truth, but I know better.

Then I leave the house.

“And scene,” I whisper.

I’m no longer Happy Paz. And I haven’t been since the first End Day when I killed my dad.