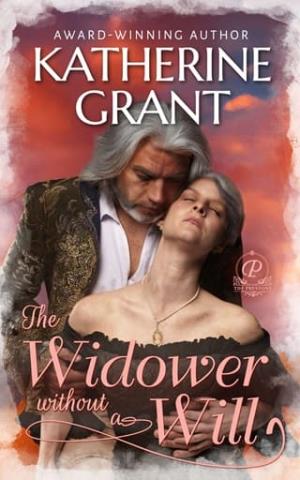

The Widower Without a Will (The Prestons #8)

Chapter One

On a beautiful summer day, Lord Martin Preston had no right to feel sorrow, yet his heart hung heavy as he drove his gig through Thatcham, the village that looked always the same yet was ever changing.

How many times, in the course of his sixty-two years, had he ridden down Chapel Street?

The same buildings with the same white plaster walls and the same thatched roofs sprouted up from the soft hills of the countryside.

But the people inside them were different.

The baker who had been a young man when Martin was a boy now lay in the graveyard under a respectable marker, while his great-grandson kept the village in fresh bread.

The shop that had once been a haberdasher’s had since been a stationer’s, a grocer’s, and now a tailor’s.

The old barn that had sat empty in Martin’s youth now stood proudly as a school for the village children.

And his dear friend Maulvi now lay in a sickbed when once he had walked daily from Thatcham to Northfield Hall and back.

At least he and Maulvi had spent a nice afternoon together.

Though he was confined to bed, Maulvi was in fine spirits, and they had read a letter from Martin’s son Nate, gotten into a debate about whether slavery would ever be abolished in Britain’s colonies, and reminisced about when they were both three decades younger and optimistic about the world.

Then the Widow Croft had eased into the room with a bowl of broth and a basin of hot water, apologizing to Martin. “I had better give Mr. Maulvi his wash now, sir.”

Strange, how Martin still thought of her as the Widow Croft when she and Maulvi had lived as common-law husband and wife since before Martin himself had married.

If they had both been Christians, she would be Mrs. Maulvi.

If she were of the same class as Martin, he might have asked her permission to call her by her first name—whatever it was.

Martin supposed his children would accuse him of having an inflexible mind, since in all these years it had never occurred to him to change how he thought of her. She was the Widow Croft; it didn’t matter what Martin called her in his head so long as she remained Maulvi’s dear partner and lover.

These ruminations kept him company as he guided the gig down Chapel Street, back towards Northfield Hall. He lifted his hand periodically to acknowledge the pedestrians greeting him, but he barely saw them, his mind turning as it so often did on thoughts that kept him away from the mundane.

Then—a flash of golden hair caught his eye. By instinct, he knew it to be his daughter Caroline, and he slowed the horse before he even consciously realized he had seen her.

Things had not been right with Caroline for years.

Not since Martin had tried to prevent her from marrying Eddie Chow.

Before, he had been her hero; ever since, she looked at him as if he were a snake who at any moment might bite her ankle.

No matter that Martin had apologized and admitted his mistakes.

At least they had semi-regular dinners where they both tried desperately to make conversation that would not upset each other.

At the moment, Caroline stood outside the pub in conversation with two other women: the publican’s wife and the late rector’s widow.

As Martin watched, Caroline shepherded the women into the shade, and her gentle words—“You see, my dear Mrs. Bellamy, there are plenty of options for you to consider”—carried in the afternoon breeze.

Mrs. Bellamy, the widow, did not look convinced.

She was a woman of roughly Martin’s age with silver hair tied in a simple knot beneath her black bonnet, a white complexion that had over the years grown tan, and a softly rounded body that demanded no notice.

Martin had met her a handful of times in the decade that her husband was rector, in the same capacity that he had met almost everyone in Thatcham a handful of times in his forty-odd years as the local baron, which meant he knew her mostly in terms of the stories that reached his ears.

Practical, community-minded, never shirking in her duties to the poor, ill, or aged.

He knew of the terrible tragedy of her life, the one that had driven her husband to seek the living in Thatcham, but he liked to assume the worst details had been exaggerated.

Martin pulled his horse to a stop and, descending from the gig, tied him to the pub’s hitching post. Of the three women, Mrs. Bellamy saw him first and took a step backward from their circle, as if he were an invading army who demanded retreat.

“Good afternoon,” Martin said as warmly as possible. He couldn’t help but touch a hand to Caroline’s shoulder—a father’s instinct to check that his child was, in fact, still there. “I am driving home to Northfield Hall and wondered if I could be of help with whatever troubles you.”

The publican’s wife, at least, looked happy to see him. She was in the generation between Martin and Caroline, perhaps in her forties, and no doubt had her hands full keeping the pub in order. “Mrs. Bellamy is seeking somewhere to stay, my lord, but I’m afraid our rooms are all let.”

“Seeking somewhere to stay?” A rector’s widow did not typically need to take a room in a pub.

“The new rector arrived today,” Mrs. Bellamy explained. Martin was surprised to discover her voice was beautiful, like a glass bell ringing in a silent chamber. “There is no room for me to remain at the rectory with his family while I wait to hear from my niece if I may live with her.”

As matter-of-factly as she delivered the information, her words quickly painted a picture of the awkward situation.

First, the new rector had every legal right to take possession of the house—but it would have been kind to coordinate with Mrs. Bellamy so she might arrange for her own move ahead of time.

Second, the late Mr. Bellamy had been deceased for more than six months already, so for Mrs. Bellamy to be without a place to stay indicated either an extraordinary lack of planning or that her family was reluctant to take her in.

Third, as everyone pretended not to know, that family was small because her only child had died at his own hand, leaving Mrs. Bellamy at the mercy of her niece.

And fourth—perhaps the most crucial element in his daughter’s eyes—this was all Martin’s fault, since he was the one who had appointed the new rector.

It was his legal obligation. If he hadn’t done so, then the bishop would have.

It was not as if Martin had thought, I would like to make a widow homeless today.

Yet he had selected the Reverend Mr. Sebright from the pool of candidates—primarily as a favor to Lord Harewood, who had in turn voted with Martin for gaol reform—which meant he was responsible for the inconsiderate rector turning poor Mrs. Bellamy onto the street.

“Of course, Mr. Chow and I would take you in,” said Caroline, triggering in Martin a second of bewilderment before he remembered she did not refer to his carpenter Mr. Yin Chow but to the son, Eddie, to whom Caroline was now married.

“We have only the one bed, however, and our second room is also the kitchen, and I can’t see that you would be comfortable.

I’m confident once we take a survey of Thatcham that we will find multiple families who will argue with each other about which one gets the favor of your company. ”

To her credit, Mrs. Bellamy was a stoic woman. She met the suggestion that the whole village be told of her embarrassing plight with only a pinch of the lips.

Martin touched Caroline’s shoulder again. “Surely that isn’t necessary.”

Caroline turned hot, angry eyes on him. “We aren’t going to send Mrs. Bellamy to an inn at Theale where she knows no one as she waits for her niece to send instructions!”

As if, in his simple sentence that had not been a suggestion at all, Martin had resurrected all the evils he had ever visited upon Caroline and insisted she live through them once more.

When, he wondered, would it occur to her that he was just a human, and that his heart could be broken, too?

“Certainly not,” he said, and he plastered on his most gracious smile as he turned to Mrs. Bellamy. “It would be my honor if you would make your home at Northfield Hall for as long as you need.”

The publican’s wife cried out, “Oh, what a wonderful idea, my lord!”

Mrs. Bellamy remained stoic. However, her lips did un-pinch ever so slightly, and her eyes—hazel—met his with a warmth he hadn’t yet experienced from her. “If I wouldn’t be in your way, sir.”

“Indeed, you would be my only company for the foreseeable future, saving me from eating endless suppers on my own.”

The wrong thing to say; Caroline would ordinarily have swooped in to correct him that he wasn’t alone, since someone was making him that supper in the kitchens and someone else was carrying it to him in the dining room (or, more often now, his study), and all he needed to do was invite the servants to eat with him if he wanted company.

But Martin had earned enough favor with her that she did not eviscerate him for failing to eradicate the class system in one fell swoop.

Instead, she clasped both his elbow and Mrs. Bellamy’s.

“There, you see, I knew there was no reason to despair! Now, Papa, is there room in the gig for Mrs. Bellamy’s things? ”

Martin almost said no, expecting Mrs. Bellamy to have a household’s worth of belongings, but he saw in a flash that her things waited by the front of the pub: one chest, two cloth bags, and a hatbox.

What would it be like, he wondered, to have one’s life reduced to so little?