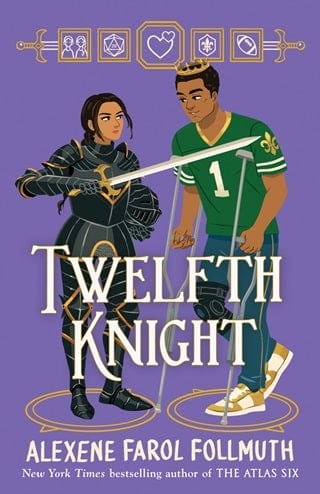

Twelfth Knight

1. Battle Theme Music

When I was a kid, everyone naturally assumed that because I was the son of Sam Orsino, I was an All-American quarterback in the making.

They were… half right.

I mean, I can see the logic. My dad, the only son of a janitor and a waitress, famously set the Northern California record for passing yards when he was at Messaline High in the ’90s, only to be surpassed four years ago by my older brother—so yeah, I have some idea of what people expect from me. The family arm! Practically my birthright. People assume I’ll be no different from my father and brother: a playmaker, a leader. Someone who can command the field, and in a lot of ways, they’re not wrong.

I do see the game differently than other people. I think the commentators usually call it vision, or clarity, even though to me it’s something more innate. When Illyria was recruiting me last fall, they said I saw the field like a chess prodigy, which feels closest to the truth. I know where people are going to be, how they’ll move. I feel it somewhere, like the tensing of a muscle. I can sense it like a change in the wind.

Like, for example, right now.

Messaline Hills, California, isn’t exactly Odessa, Texas, but for an affluent San Francisco suburb, we know how to pull off your classic Friday-night lights. The late-August heat burns away as the sun molts into stadium brights, transforming the familiarity of our home turf to the singular mythos of game day. The stands are packed; whoops and chatter buzz from the crowd, all alight with Messaline green and gold. There’s a snap from a drumline snare, sharp like the edge of a knife. From the field, the tang of sweat and salt mixes with the charred scent of barbeque, the storied hallmark of our home opener’s Pigskin Roast.

Tonight, standing on this field for my final year feels like the start of an era. Destiny, fate, whatever you want to call it—it’s here on the field with us; I can sense it from the moment our next play is called, my team collectively suspending in time for the same fleeting breath.

“HUT!”

There’s immediate pressure on Curio, our quarterback, so I force some space and quickly change directions, shaking off a linebacker to reach Curio’s left for the handoff. We’ve run this exact play hundreds of times; it worked last week in our season opener, an away game against Verona High, and it’s going to work again now. I take the ball from him and spot an oncoming defender, shouting for a blocker to take my right. Naturally he misses, so I pivot again to drop a right-side defender. He can’t hang. Too bad, so sad.

Now it’s just a forty-yard run with the entire Padua defense at my heels.

You know how I said everyone was half right about me following in my dad’s footsteps? That’s because I’m an All-American running back. It’s who I am, what I love. After watching me take off with the ball every chance I got during my first peewee season, my coach had the foresight to start me at running back instead. My dad supposedly threw a fit—once prophesied to be the rare Black quarterback who could rival Elway or Young, his career had ended abruptly, with an injury cutting his pro dreams short. Naturally, he saw in his two sons the mirror-slivers of his own glory, craving for us the greatness foretold for himself.

But when I took off for the full length of the field, even King Orsino couldn’t argue with that. They say every great football player’s got some supernatural spark, and mine—the thing that makes me the best player on the field—is that when I catch even a glimpse of an opening, I can outrun anyone who tries to stop me. What I’ve got absolute faith in is the pulse in my chest, the sanctity of my own two feet. The knowledge that I will fight my way back up from every hard fall. Most people don’t know what their purpose in life is, or why they exist, or what they were meant for, but I do. In the end, it’s a very short story.

In this case, only forty yards.

By the time I’m across the goal line the band is blasting our school fight song, the whole town going wild in the stands. As far as home openers go, I’m definitely giving them a show, and they return the favor with their usual chant—“Duke Orsino,” a variation on my father the king and my brother the prince.

This year, nobody uses the phrase if we win State, but when.

I toss the ball over to the ref while glancing at the too-late Padua cornerback, who looks less than pleased about me scoring on his watch yet again. He’s probably the fastest person on his team, which must seem like a hell of an accolade if you haven’t met me. Some people really take issue with coming in second—just ask Viola Reyes, the student body VP to my president. (She demanded a recount after the results had us coming in within twenty votes, ranting something about election protocols while staring me down like my popularity was somehow both malicious and personal.) Unfortunately for the Padua cornerback—and Vi Reyes—I really am that good. The speed and agility that secured my spot at Illyria next fall isn’t something to sneeze at, and neither is the fact that I spend every minute of every day being likable enough for ESPN.

With… minor exceptions. “A little more steam next time,” I advise the cornerback, because what’s a game without a little smack talk? “Few more sprints and you’ll have it.”

He scowls and flips me off.

“ORSINO!”

Coach motions me over to the sideline as we swap with special teams, rolling his eyes when I saunter over with what he calls my “eat shit” grin.

“Let your runs do the talking, Duke,” he grunts to me, not for the first time.

Humility’s easy to preach when you’re not the one being lauded by the crowd. “Who says I’m doing any talking?” I ask innocently.

He glances at me sideways, then gestures to the bench. “Sit.”

“Sir, yes, sir.” I wink at him and he rolls his eyes.

Did I mention that Coach occasionally goes by Dad? Yep, that’s right—King Orsino became Coach Orsino, and thanks to his work in the community as varsity football coach, he’s still the local boy made good. He won Man of the Year last year from the Bay Area Black Business Association, plus he’s been honored at almost every school function in the last decade. Together, our wins while proudly wearing Messaline emerald and gold afford us a rare place in this town’s predominantly white history.

When it comes to the Orsino skill on the field, some call it luck. We call it a legacy. Still, compared to my father and brother, I’ve got a lot more to prove. At my age, they were both All-Americans and top-recruited NCAA prospects, too—but unlike me, they had State Champion titles under their belts by the start of their senior season. I may be the best running back in California, arguably the country, but I’m still fighting my way out from under a shadow that goes for miles. As far as nicknames go, Duke Orsino is a great one until you consider what that actually means in terms of lineage. Every year is a vicious new experiment in close, but no cigar.

Still, it’s a good thing I’ve got such a powerful motivator, because while I’m having the game of my life tonight—I’ve already run for two hard touchdowns so far, bringing me within a single good run of the Messaline record for career yards gained—Padua’s got a battalion of big defenders putting in work to keep our offensive line at bay. Our defense is holding their own against Padua’s sleeve of trick plays, but Curio, our senior QB who’s finally risen through the ranks, isn’t nearly the player Nick Valentine was in his senior season. It’ll be up to me to make sure we’re getting that ball to the end zone come hell or high water, which means my all-time record is definitely getting broken tonight.

I shake myself at the sound of the Padua crowd’s cheers; their receiver makes an incredible catch that leaves our side of the stands groaning. This will be a tough one, definitely. But these stakes, however crucial, are no different from any other game. It’s always about the play right in front of me, and the moment it passes, we’re on to the next one.

Ever forward. Ever onward.

I roll out my neck and exhale, rising to my feet at the exact moment that a perfect spiral gets Padua to first and goal. If they score here, it’s our turn next. It’s my turn. My moment. Everyone I know is out there in the stands holding their breaths, and I won’t let them down. Before I walk off the field tonight, they’re all going to bear witness to my destiny: a winning season.

A state championship.

Immortality itself.

Am I being dramatic? Yes, definitely, but it’s hard not to be romantic about football. And I don’t think it’s unreasonable to say there’s always been something waiting for me. Something big, and this is my chance to take it.

So right now, it’s time to run.

Things in the game are definitely getting heated. We’ve lost some of our best players from last year, and with a pace this arduous, focus is everything, so getting this team to a win is going to take… well, a miracle.

But miracles have been known to happen.

“They’re coming” is all Murph says. Instantly, I feel a shiver. This is the exciting part, but also the time when most mistakes are made. I lean forward, anxious but not concerned. We can do this.

(We have to do this. If we don’t, there’s no way I get my shot, and that’s just not an acceptable alternative.)

On my left, Rob Kato’s the first to respond. “How many are there?”

Murphy, or Murph (whose real name is Tom, though nobody calls him that—honestly, don’t bother learning anyone’s names, they’re really not important), says from across the table, “Ten.”

“Some people will have to take two.” That’s Danny Kim. He’s new—not just to the group, but to the game itself. Which is exactly as helpful as you’d expect, and he’s just as unworthy of committing to memory. (I’d happily number them instead for ease of consumption, but I’ve been in all the same AP classes with them for the last, oh, four hundred years, so for purposes of atmosphere, let’s pretend like I care they exist.)

“I will,” volunteers Leon Boseman, on Rob’s left. The boys call him Bose or Bose Man, a brotastic endowment of reverence with no meaningful effect on his personal appeal.

“And me,” I say quickly.

“What?” That’s Marco Klein, on Murph’s left. He’s a huge bitch. But I’m used to him, so better the devil you know, I guess.

“Check my character sheet, Klein,” I growl. “I’ve got a black belt in—”

From outside Antonia’s kitchen window there’s a sudden, deafening roar, followed by the blast of a marching band.

“Ugh, sorry.” Antonia rises to her feet and closes the window. “Gets so loud on game days.”

The distant sounds of high school football are successfully muffled, leaving us to return to our kitchen table game of ConQuest. Yes, that ConQuest, the role-playing game for nerds, ha-ha, we know. The thing is that 1) we are nerds, by which I mean we collectively make up the top 1 percent of our graduating class and are probably going to rule the world someday even if it loses us some popularity contests (don’t get me started on the idiotic grift that is student body elections, I will throw up), and 2) it’s not just for antisocial weirdos in basements. Did you know that tabletop role-playing games like ConQuest are the forerunners to massive multiplayer online RPGs like World of Warcraft and Twelfth Knight? Most people don’t, which drives me crazy. I hate when people dismiss revolutionary forms of media just because they don’t understand them.

Though, don’t get me wrong—I get where the misconception comes from. Murph’s floppy ash-blond hair is currently swept forward to cover an Orion’s belt of cystic acne. Danny Kim has anime-style black hair that still doesn’t take him past my shoulder. Leon is best known for his hyena cackle; Rob Kato’s prone to uncontrollable stress sweats; Antonia—the only person here I actually like or respect, by the way—is wearing a hand-knitted vest-thing that’s more lumpy than trendy; and hey, even on a good day I still look like I might be twelve, so current company might not be the perfect sell. Still, this game is a revolution, regardless of whether a bunch of high-achieving teens have settled into their post-pubescent forms or not.

“You were saying?” Antonia prompts me, though I’m still annoyed with Marco. (He once begged me to make Murph invite him, as if Murph has ever been in charge.)

“I’ve got a black belt in Tawazun,” I finish irritably. It’s Arabic for balance, and one of the five major fighting disciplines from the original ConQuest game. They say that War of Thorns—my favorite TV show, a medieval fantasy adaptation about warring kingdoms—originated from a massive homebrewed ConQuest campaign that the book series’ author, Jeremy Xavier, played QuestMaster for when he was a student at Yale. (He’s kind of my hero. Every year I cross my fingers that I’ll run into him at MagiCon, but no luck yet.)

“Isn’t Tawazun like, ceremonial fan fighting or something?” says Danny Kim, who, once again, doesn’t know anything. Yes, there are hand fans in Tawazun, but the use of a fan as a weapon is not uncommon in martial arts. And anyway, the point is that it’s all about using your opponent’s momentum against them, which makes it a super practical choice for a smaller female character like Astrea. (That’s me: Astrea Starscream. I’ve been role-playing as her for two years now, refining her story a little more each campaign. Basically, she was orphaned and trained in secret as an assassin for hire, but then she found out her parents were murdered by the people who trained her and now she wants revenge. A tale as old as time!)

Before I can correct yet another of Danny Kim’s annoying misconceptions, Matt Das answers. “Tawazun is basically jiu jitsu.”

“And either way, I said I could do it,” I add, “which is all you need to know.” There hasn’t been much combat yet; we got into a little skirmish earlier with some bandits, leaving us with a small onyx arrowhead that none of us know what to do with. Still, I shouldn’t have to prove anything to him.

“Why don’t you just, like, seduce him?”

Okay, I kind of hate Danny Kim. “Do you see ‘seduction powers’ listed anywhere on my Quest Sheet?” I demand, this time not very patiently. Danny exchanges a glance with Leon, who brought him here, and suddenly I want to smack both their heads together like a pair of coconuts. But I don’t, of course. Because apparently I’m supposed to be nicer if I want people to agree with me. (Big ups to my grandma for that sage advice.)

“Believe it or not, Danny,” I say with a pointed smile, “I’m just as capable of imaginary martial arts as you are.” More so, actually, since I’ve done Muay Thai with my twin brother Bash for the last four years. (Bash does it for stage combat, but I do it for moments like this.)

Danny Kim doesn’t smile back, so at least he’s not a complete idiot.

“I can try something,” Antonia cuts in, ever the peacemaker of the group. “I’ve got a love potion that might work. Feminine wiles or whatever, right?”

She did not just say feminine wiles. I love her dearly, but come on.

“Is that your official move?” Murph asks her, reaching for the dice.

I smack a hand out to stop him because for the love of god, ugh. “Larissa Highbrow is a healer,” I remind the rest of the table, because every campaign, without fail, leaves at least one of us in need of Antonia’s healing powers in order to keep going. She’s basically the most crucial character here, which naturally the boys are unable (or unwilling) to recognize. “You should stay back and tend to the wounded.”

“She’s right,” says Matt Das, who’s surprisingly helpful despite being new to our group. (Matt is tan and wavy-haired and seems well acquainted with deodorant, so if I cared what anyone here looked like, I’d say his appearance was reasonably good.) “The rest of us can handle combat amongst ourselves.”

“Or—” I begin to say, only to be interrupted.

“Can we stop talking about this and actually fight?” whines Marco.

“Or,” I repeat loudly, ignoring him, “maybe we should try diplomacy first.”

In unison, the boys groan. Except Matt Das.

“Uh, they’re coming at us with axes,” says Rob.

“Murph didn’t say shit about axes,” I remind him, since as QuestMaster, Murphy’s the one who narrates the game and gives us the information we need. And likewise, he doesn’t give us information that’s not applicable. “Do they have weapons, Murph?”

“You can’t see from this distance,” Murphy answers, briefly skimming the page in the QuestMaster’s Bible (it has a stupid name and I covet it). “But they’re getting closer by the minute,” he adds, reaching blithely for a pizza roll.

“They’re getting closer by the minute!” Rob informs me urgently, as if I cannot also hear what Murph just said.

“I get that, but it might be a mistake to just assume they’re armed. Remember what happened to us in the Gomorra raid last year?” I prompt, arching a brow as they all nod, minus Danny Kim, who still knows nothing. “We don’t even know if these guys are with the rest of the army.”

Luckily for me, I’m being blatantly ignored.

“I say we shoot first, ask questions later,” says Leon, blowing off the invisible barrel of an imaginary pistol even though his character, Tarrigan Skullweed, specifically uses a bow and arrow.

I glance witheringly at him. He winks at me.

“How far away are they?” Antonia asks Murph. “Is there a way that someone can get closer to see whether they’re armed?”

“Try it and see,” invites Murph, shrugging.

“Oh sure, does anyone volunteer to fall on that grenade?” demands Marco.

Okay, this is exhausting. “Fine. Combat it is,” I say, “and let the die be cast.”

“Is that from War of Thorns?” asks—who else—Danny Kim. Yes, it is, and it’s also from a scene right before Rodrigo, the main protagonist who is honestly kind of a dud compared to the other characters, leads his army into a losing battle.

“Whose turn is it?” I ask loudly.

“Mine.” Rob sits up. “I take my sword and throw it directly at the heart of the biggest warrior.”

Well, that’s typical, but at least Rob’s character, Bedwyr Killa (I know, eye roll, but it’s actually not the worst of the bunch), is massive and strong in addition to being impractically reckless.

Murph rolls. “It’s a successful hit. The leader of the group falls to the ground, but just as he does, his arm comes up, and—”

Oh my god. I swear, if he’s holding a white flag…

“—the white piece of cloth in his hand flutters to the ground,” Murph concludes, and I groan. Of course. “The rest of the horde falls around their leader in anguish.”

“Great work, boys,” I sarcastically applaud them.

“Shut up, Vi,” says Marco half-heartedly.

“So what now?” asks Matt Das.

If I were in charge? We’d use Antonia’s character’s magic to heal him and resolve the conflict, possibly trading with the horde for supplies or extracting information about the missing gems that make up the whole purpose of this campaign. But I already know there’s no point bringing that up—if I’m going to successfully parlay the group’s good graces by the end of the night, then I need to win this game their way.

If the boys crave violence, then violence they shall have.

“We’ve obviously got to fight now, don’t we? I’m next,” I remind them, turning to Murph. “I approach the horde’s lieutenant and offer safe passage in exchange for surrender.”

Murphy rolls. “No go,” he says with a shake of his head. “The lieutenant demands blood and lunges, aiming a knife at your chest.”

We do the usual contested strength check, but I know my skills. “I wait until the last possible moment, then slip the knife, twisting his arm around and directing it into his kidney.”

Murphy rolls again. “It’s a critical hit. The lieutenant is down.”

I sit up straighter, pleased. The boys look impressed, which reminds me that even if they’re the portrait of incompetence, I do actually want them to believe I can handle this.

“I take the next biggest one,” says Marco. “With my mace.”

“I shoot an arrow,” adds Leon.

“At what?” I ask, but he waves me away.

“Arrow lands in the blade of a horde member’s shoulder, but it’s not fatal. Mace is a swing and a miss,” says Murph.

“Another swing,” says Marco.

“I use my lasso,” says Matt Das, whose character is kind of weirdly Western—a vestige from an old campaign, I suspect.

“Lasso holds, but not for long. Mace lands, but now they’ve got you surrounded.”

The others are excited about the possibility of battle, but what everyone always forgets about ConQuest is that it’s a story. As in, there are good guys and bad guys, and all the characters have motives. Why would the horde come over with a white flag? We must have something they want. They’re built into the quest regardless of who our characters are, so it has to be something we’ve picked up within the game. That weird arrowhead…?

Oh my god, I’m an idiot. The quest is literally called The Amulet of Qatara.

“I remove the Amulet of Qatara from my holster and hold it aloft,” I blurt out, shooting to my feet, and everyone turns to stare at me. Blankly. (This is why I hate playing with people who don’t pay attention. It actively makes me dumber.)

Murph, however, gives me a noncommittal thumbs-up. “The fighting stops,” he says, “and the horde requests a personal parlay with Astrea Starscream.”

Finally. It’s time to get this done.